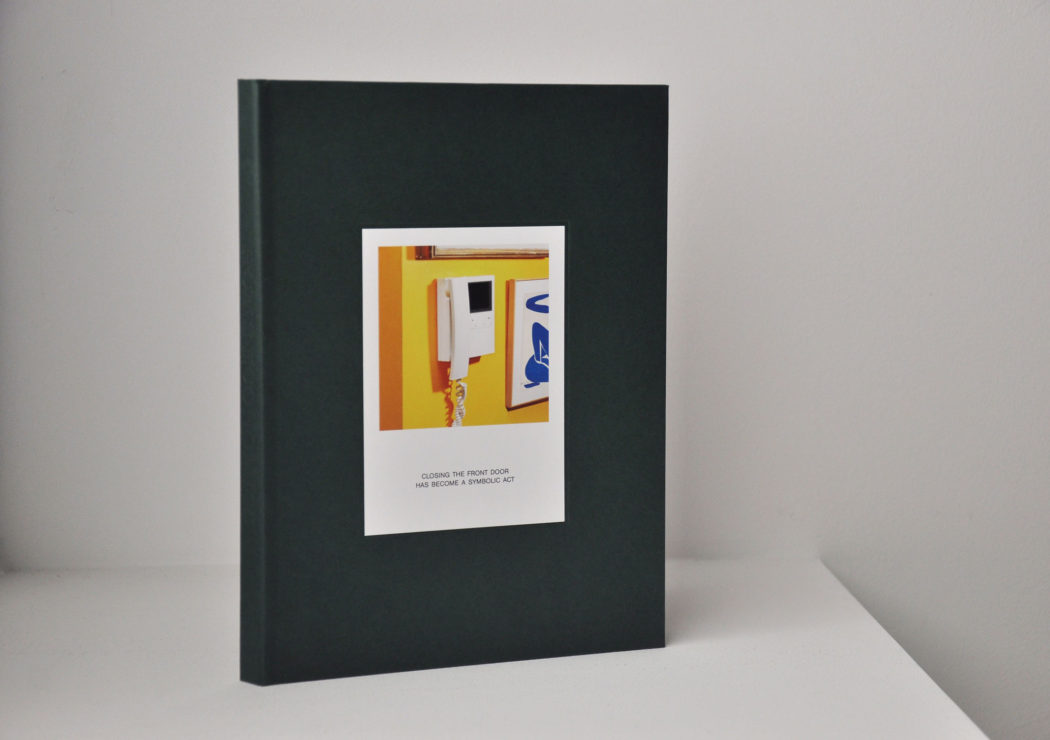

Home Economics is a book designed to complement the exhibition of the same name. Normally, this would make Home Economics a catalogue – but this publication is the exact opposite.

It does more than simply represent or record, it proposes, and it reframes the publication as a project in its own right. Home Economics aspires to be a clear statement of intent, a (rather modest) manifesto, and a book with a proposition that can function entirely independently of the exhibition it was commissioned to accompany.

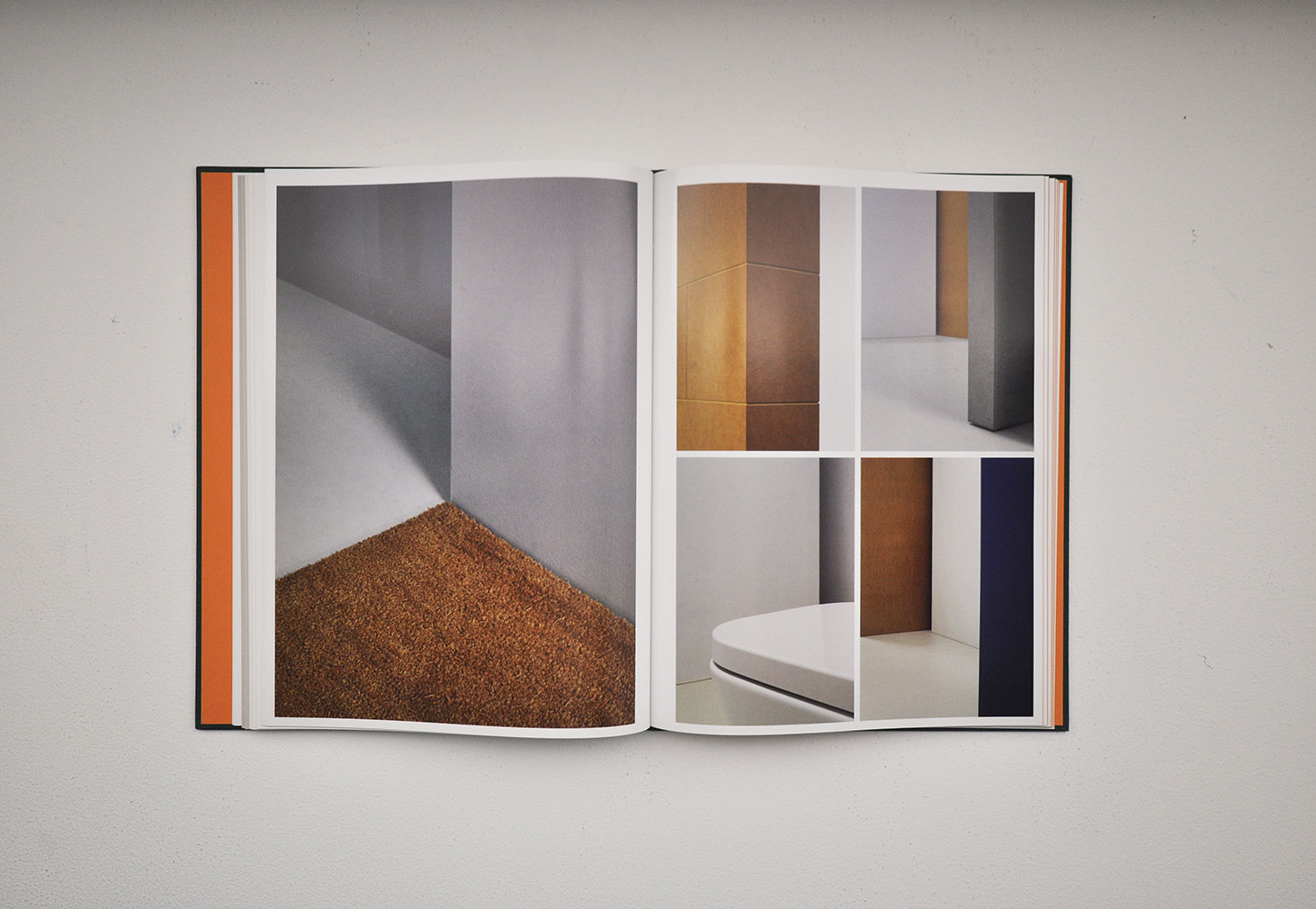

Featured are essays from Britain’s foremost writers and critics; architectural projects (including those commissioned for the show but not exhibited); photographic artworks that capture the spaces and provoke our assumptions about the home.

So why did the curators of the British Pavilion – myself, Finn Williams and Shumi Bose – conceive of such an ambitious book to mirror our exhibition at the 2016 Venice Architecture Biennale? And why did The Spaces support such an idea?

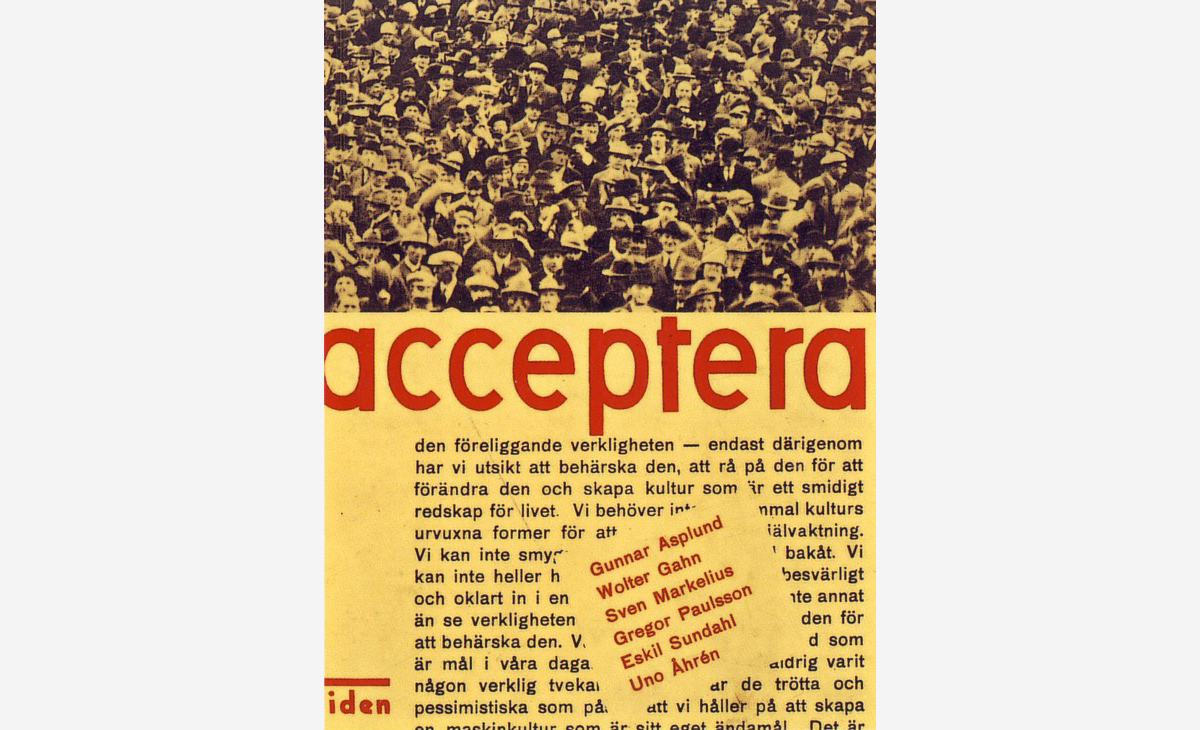

An important reference for the curatorial team when planning the book was the catalogue that followed the Acceptera exhibition, which took place in Sweden in 1931. We tend to think of Modernism as a movement that tried to sweep away the past and make a clean break with history – what makes Scandinavian Modernism practically unique is that the first major exhibition of Modernist architecture argued for the polar opposite.

Its instigators pointed to Victorian lace and dim rooms filled with dusty ornaments and said that in the past Scandinavian spaces were always clean, simple, filled with plain wooden furniture and brightly lit. With a clever twist, they suggested that Modernism was an extension of the most authentic forms of traditional architecture. It was this point that contributed to its success and mass acceptance (in fact Acceptera translates as ‘you must accept!’).

Their ‘catalogue’ was released almost a year after the exhibition closed. This book, also titled Acceptera, put the cart before the horse in catalogue terms: it was really a manifesto for Modernism and, since there were so few Modernist buildings in Scandinavia, it used the buildings of the exhibition to illustrate its argument. This is contrary to what one might expect, when the buildings are presented first and captioned to explain their purpose.

Home Economics, like Acceptera, is an exhibition of architecture at a life-size full-scale level. And while it is unlikely to be the beginning of a new movement, it does try to use the idea of an accompanying publication as a way to bring ideas about ownership, new forms of life, changes to domestic use, and the economics and politics of the home to a mass readership. The book is designed for a general audience, to be as engaging and as inclusive as the exhibition itself.

Of course, a big difference for Home Economics is that we couldn’t wait a year to release a book. It had to be ready and available on the first day of the show. To do this and include exhibition photography we had to pull installation forward by two weeks and use cutting-edge printing technologies (so-called ‘just-in-time’ production). This put the photographer whose beautiful photo-essay features in the catalogue, Thomas Adank, under immense pressure – he worked almost round the clock for several days to get the work completed.

Home Economics (the exhibition) contains almost no wall text, which is provided instead in a small pamphlet. The idea behind this is to give visitors more freedom to engage and explore with the spaces, rather than force them to stand and look at walls.

But this also creates a layered experience: someone with no knowledge could enter and grasp certain aspects from their time in the spaces alone; another person might read the pamphlet and have a deeper understanding of the themes and the works; and a third, armed with the book, would be able to fully understand the research, complexity and ambitions of the exhibition.

The book should not be seen as an addendum or addition – it is integral and a central part of the exhibition.

This publication is the product of a long chain of creative decisions: the British Council, who took a chance on commissioning the youngest ever curators to execute the pavilion; us curators, who then conceived and edited an extremely ambitious book (with design by OK-RM); and most importantly the publishers, The Spaces and the REAL foundation.

As one of the curatorial team for the pavilion, and as co-publisher for REAL foundation and editorial director for this book, I have to say that the partnership formed with The Spaces has been a meeting of minds. They have supported every proposal – even those that seemed impossible, like including show photography. Their experience from their own practice, which asks many of the same questions about what it means to live today, has been invaluable.

The quality of the book has only been made possible by their support for radical creative projects and a desire to have a long-term commitment to the promotion of new ideas about architecture.

Home Economics: five new models for domestic life, is published by The Spaces, £25.