Missouri State Penitentiary. Photography: Brett Leigh Dicks

Montana State Prison. Photography: Brett Leigh Dicks

Missouri State Penitentiary. Photography: Brett Leigh Dicks

Montana State Prison. Photography: Brett Leigh Dicks

Montana State Prison. Photography: Brett Leigh Dicks

Montana State Prison. Photography: Brett Leigh Dicks

Eastern State Penitentiary, Philadelphia. Photography: Brett Leigh Dicks

Eastern State Penitentiary, Philadelphia

High Plains Correctional Facility, Brush

Nevada State Prison

Nevada State Prison

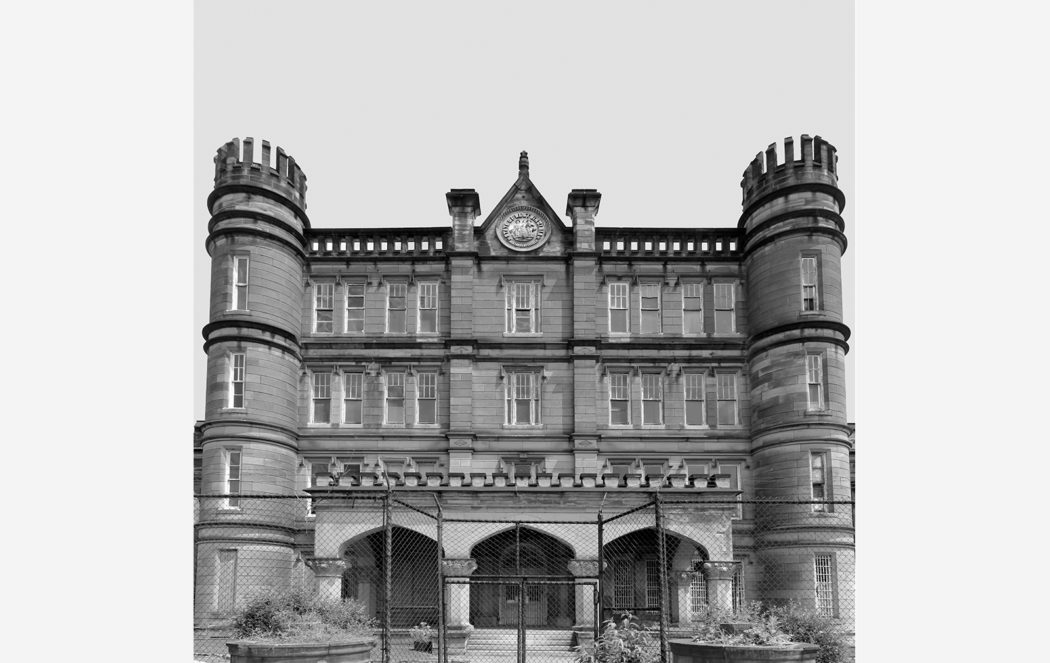

West Virginia State Penitentiary. Photography: Brett Leigh Dicks

Penitentiary of New Mexico. Photography: Brett Leigh Dicks

Penitentiary of New Mexico. Photography: Brett Leigh Dicks

West Virginia State Penitentiary. Photography: Brett Leigh Dicks

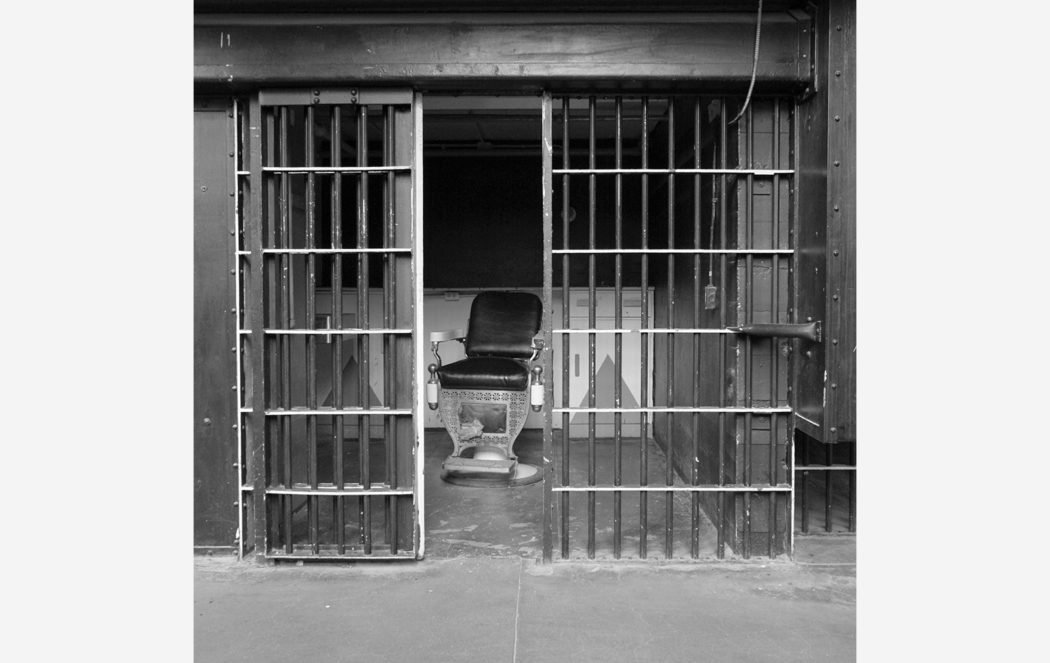

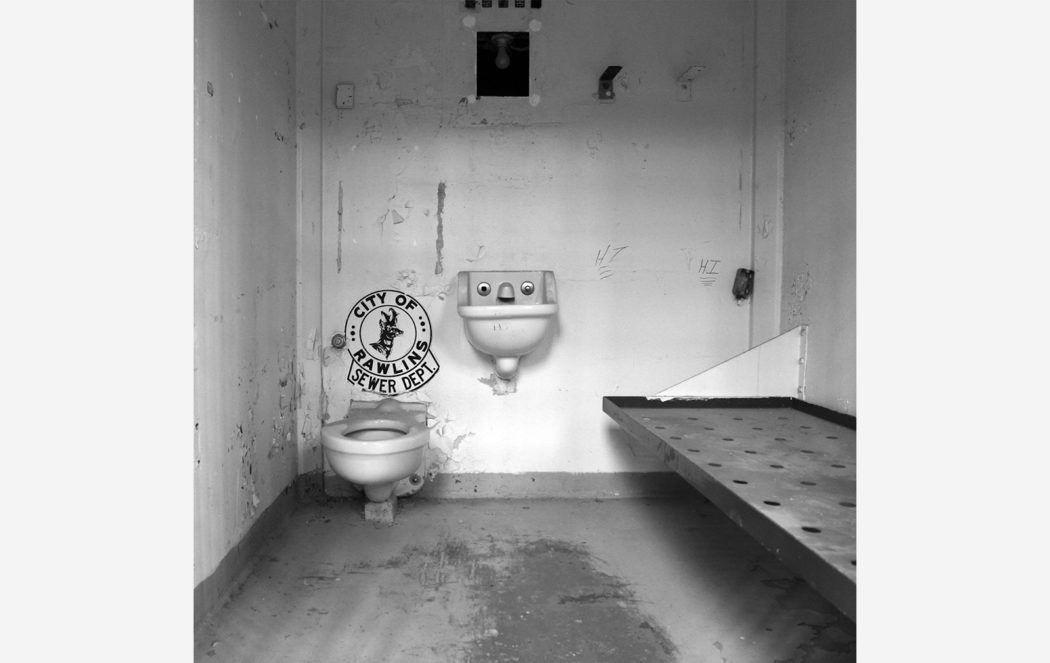

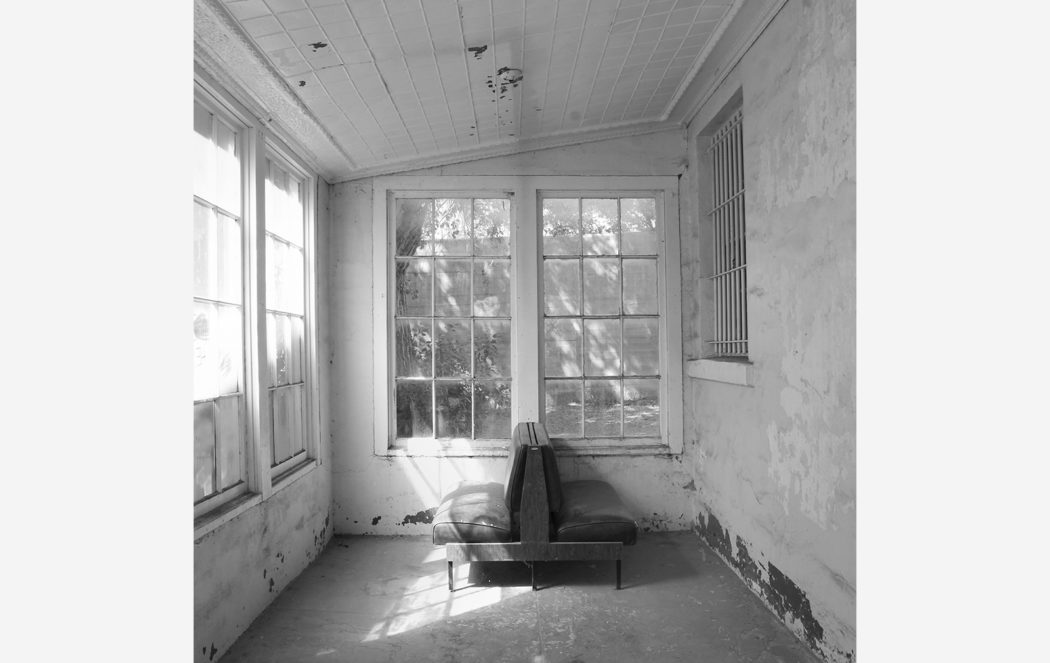

Wyoming Frontier Prison. Photography: Brett Leigh Dicks

Wyoming Frontier Prison. Photography: Brett Leigh Dicks

Wyoming Frontier Prison. Photography: Brett Leigh Dicks

Photographer Brett Leigh Dicks began photographing abandoned prisons by accident. A trip along the Ohio River took him to a town called Moundsville, where the big local employer was once the West Virginia State Penitentiary – now derelict. Curiosity led him to explore the site.

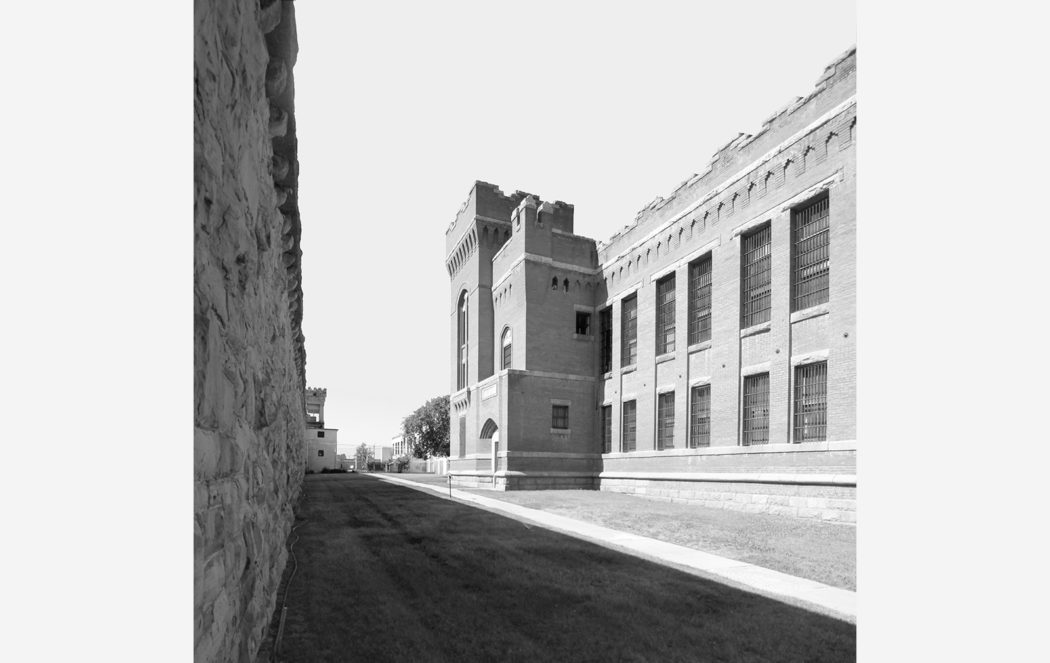

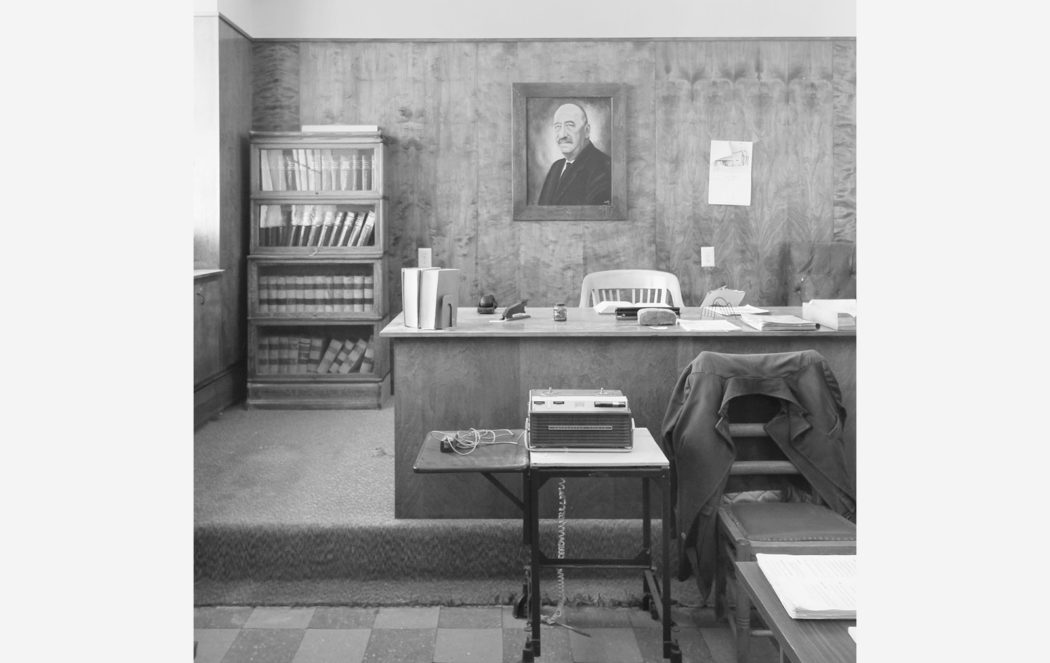

‘I was captivated by its haunting, gothic-style architecture and how it was a world unto itself with 120 years of history carved into its walls,’ he says. This encounter evolved into ‘a concerted effort to explore and document decommissioned prisons the world over’.

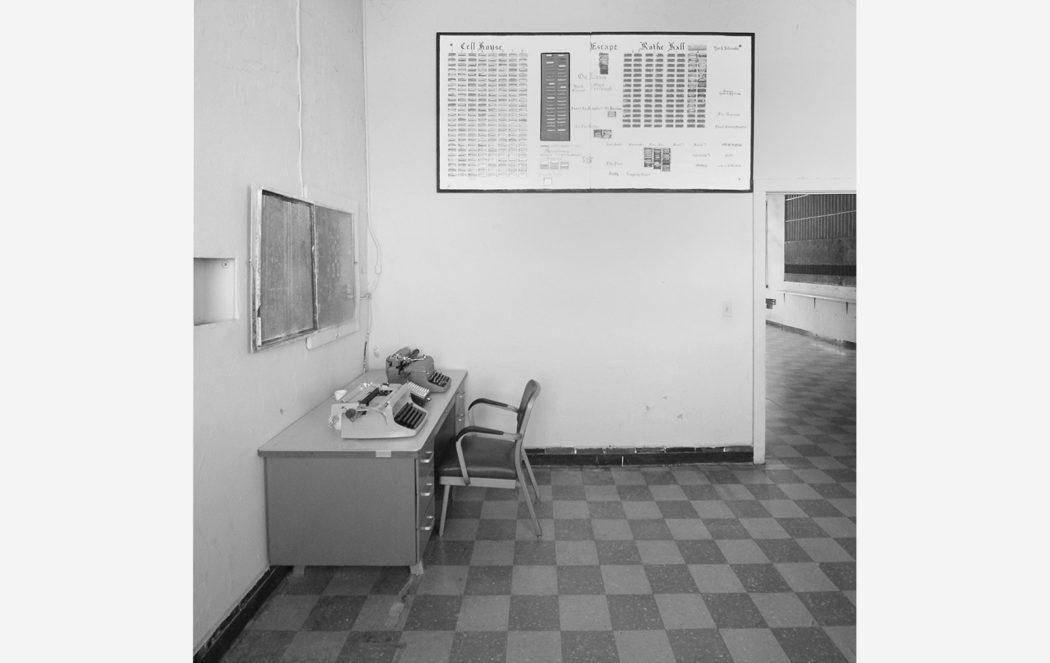

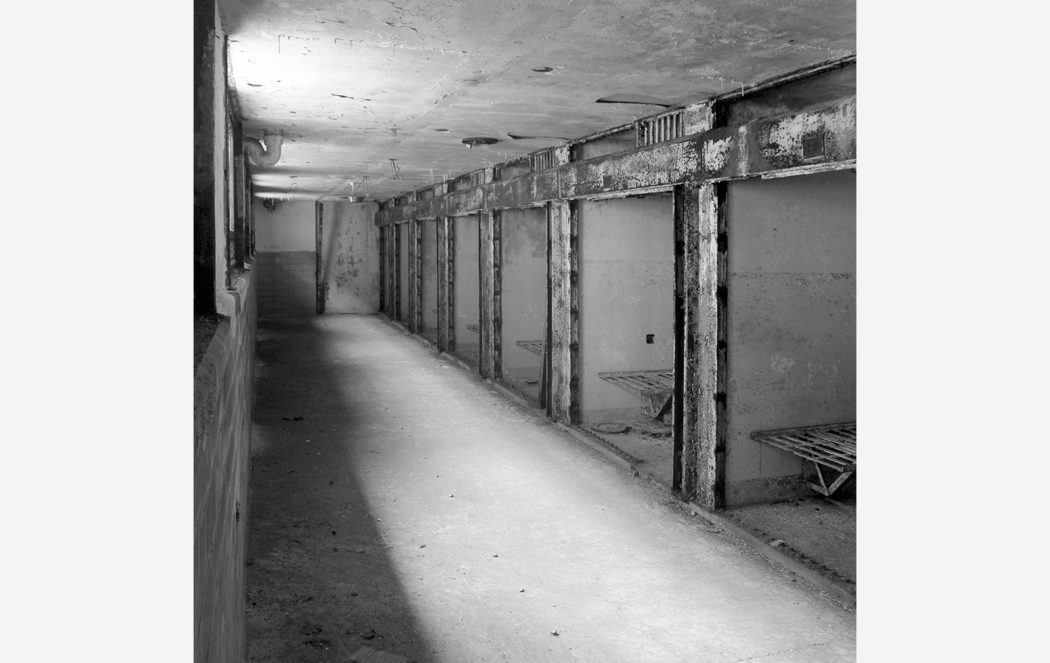

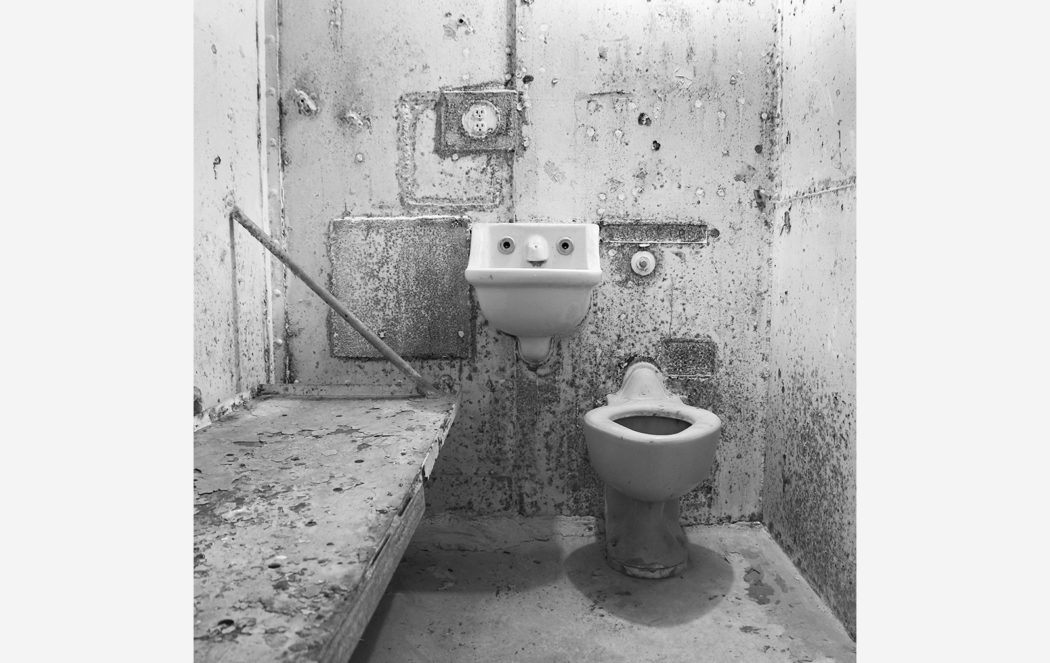

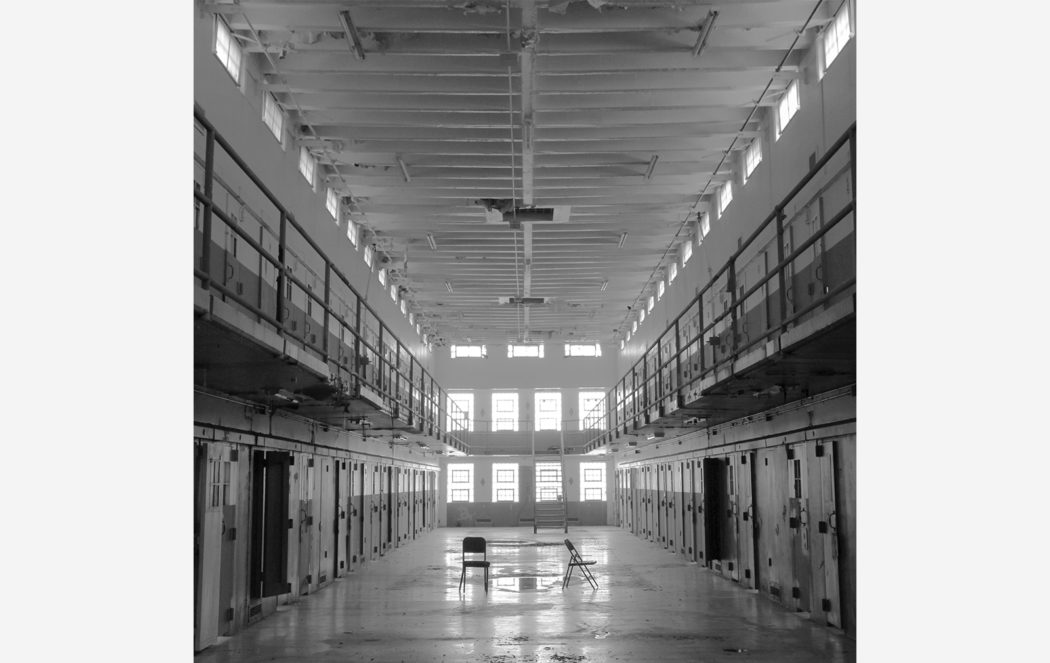

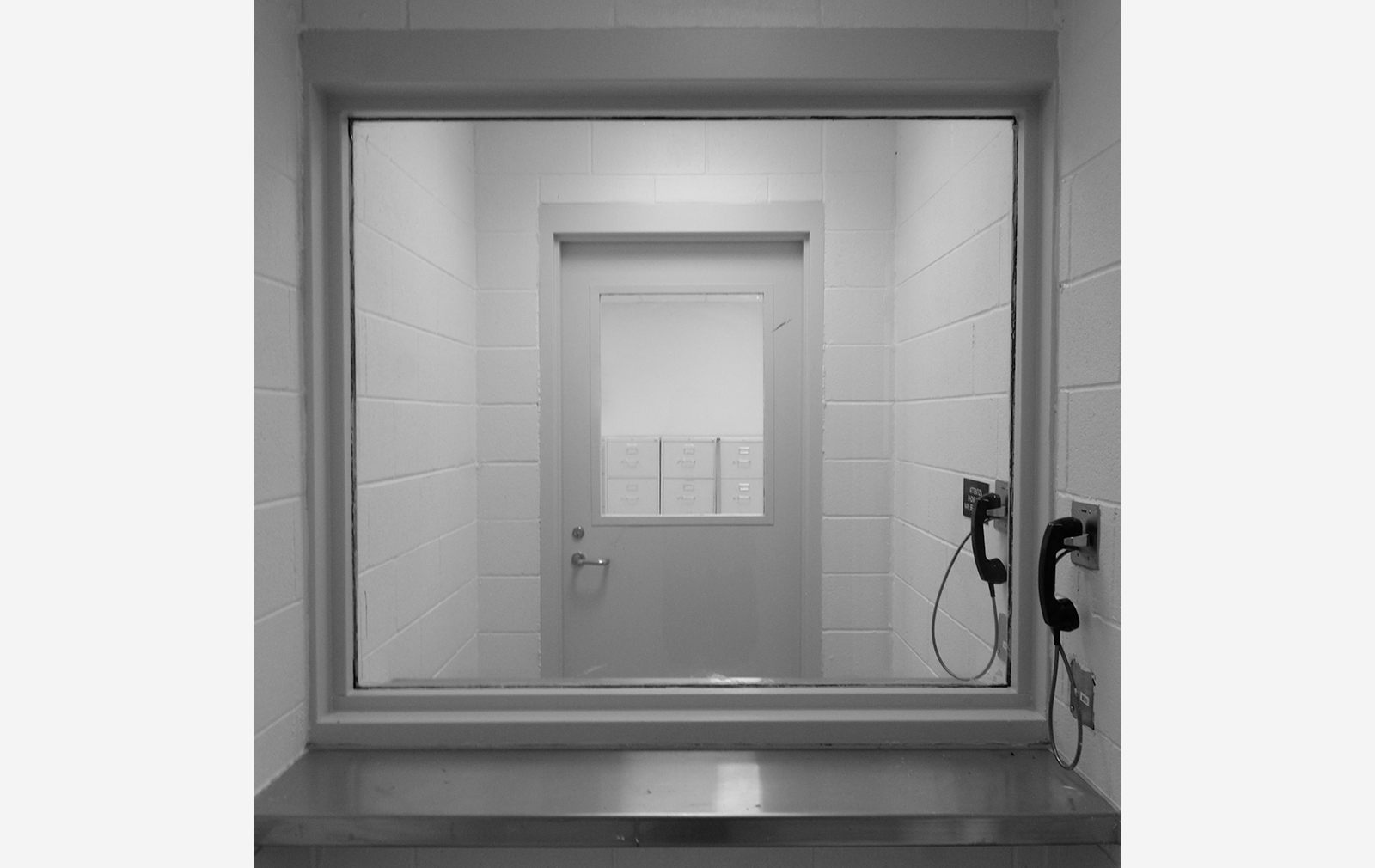

The result is Abandoned Prisons, a photographic series exploring the afterlife of jails and how their architecture, having lost its built purpose, alters in neglect. Shot in eight locations, including Montana State Prison, Wyoming Frontier Prison, Nevada State Prison, and the Penitentiary of New Mexico, the images depict every part of prison life – the canteen, the cell, the bathroom, the sports field, the execution chamber with the electric chair, the execution table for lethal injection – now emptied of their inhabitants.

For Leigh Dicks, the absence of prisoners didn’t diminish the impact of the structures. ‘Emotion is inherent in these spaces and even in their quietness, prisons are still emotionally charged,’ he explains. ‘It just plays out a little differently.’

One image shows a tiny cell, plaster crumbling from the walls, sun pouring through a skylight. Another depicts the mural in the canteen, a tantalising vision of sheep wandering through a forest under a vast sky. The graffiti on the bathroom wall warns ‘the reaper is watching you’.

Another shot is simply of shoe prints painted on the floor, in fact the spot where prisoners were asked to stand as their final photograph was taken prior to entering the execution chamber. The overall picture created is of the harsh, fearful realities of day-to-day prison life jostling with the fantasies and hopes of inmates about the outside world.

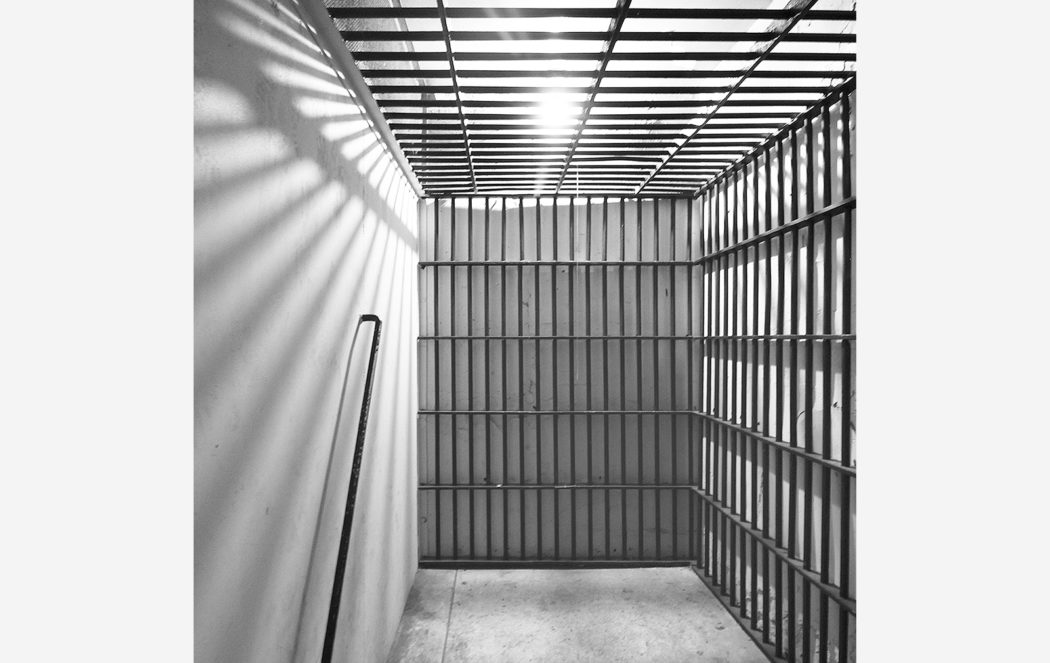

As architectural structures, penitentiaries are designed to intimidate and deter, an effect which lasts even after their abandonment. ‘The experience of exploring these prisons is filled with contrasts’, says Leigh Dicks. ‘Empathy, sadness, shock, and anger – walking through an old prison can summon all of those things. But despite their design and despite their purpose, light still manages to fill the spaces.’

For the photographer, this series is an archaeological one, about the preservation of the past as it crumbles. But this is not to ignore the relevance the pictures have for today. ‘Justice and the form it takes should be an ongoing conversation in every community and I think there is a place for photography to illuminate that,’ he says. ‘When examining important contemporary issues, photography can be a poignant reminder of past directions.’

Read next: Abandoned medical centres captured by Ilan Benattar