As the organisers of the recently concluded World Expo in Milan look to clarify the future of its 110-hectare site in the north of the city, questions are once again being raised over the legacy these events leave behind. Without Expos, Paris might not have the Eiffel Tower and Seattle would be without its Space Needle, but do a few privately owned monuments justify the enormous expense and upheaval that hosting an Expo demands?

The Italian prime minister Matteo Renzi recently announced plans to transform the site of this year’s Expo into a technology park, at a cost of €150 million per year for the next 10 years. Protesters who argued before the event that ‘Expo is a machine for burning public money,’ are likely to find this news hard to swallow. But creating a legacy for Expos is no easy feat, as evidenced by the struggles of Seville, which ran out of money to remove many of the pavilions erected for the 1992 Expo and subsequently incorporated them into a science and education park.

According to Expo 2015’s design director Matteo Gatto, rather than any specific landmarks, a key legacy of the fair will be the public spaces it leaves behind, which he hopes will provide a foundation for the site’s redevelopment. ‘Around these empty spaces we can design the future of this area,’ Gatto has said. ‘But how it will all turn out is, unfortunately, very uncertain.’

The organisers of this year’s Expo did at least encourage participating nations to consider potential future uses for their pavilions and develop designs that can be demounted and moved following its conclusion.

‘Significant resources are poured into creating these pavilions so the potential to relocate and reuse after the Expo is a massive opportunity,’ says Nottingham-based artist Wolfgang Buttress, who designed the British pavilion. Buttress received the BIE Gold Award for Architecture and Landscape for his beehive-inspired honeycomb structure, surrounded by a large area of low-cost, low-impact landscaping.

‘The Hive was designed as a kit of parts that are mechanically fixed for ease of assembly and disassembly,’ Buttress explains, adding that some of the landscaped elements have already been moved to new sites in Milan, while negotiations are ongoing with several organisations interested in re-erecting the pavilion.

Structures that can be moved and reused offer an intelligent solution to the issue of legacy, but buildings that remain on an Expo site must be able to evolve to meet the changing needs of the city.

The enduring icons of Expo architecture tend to be truly innovative examples of design or engineering, capable of encapsulating and communicating the zeitgeist to subsequent generations. The following structures from around the globe show what it takes for an Expo pavilion to survive and prosper long after the fair has packed up and left town.

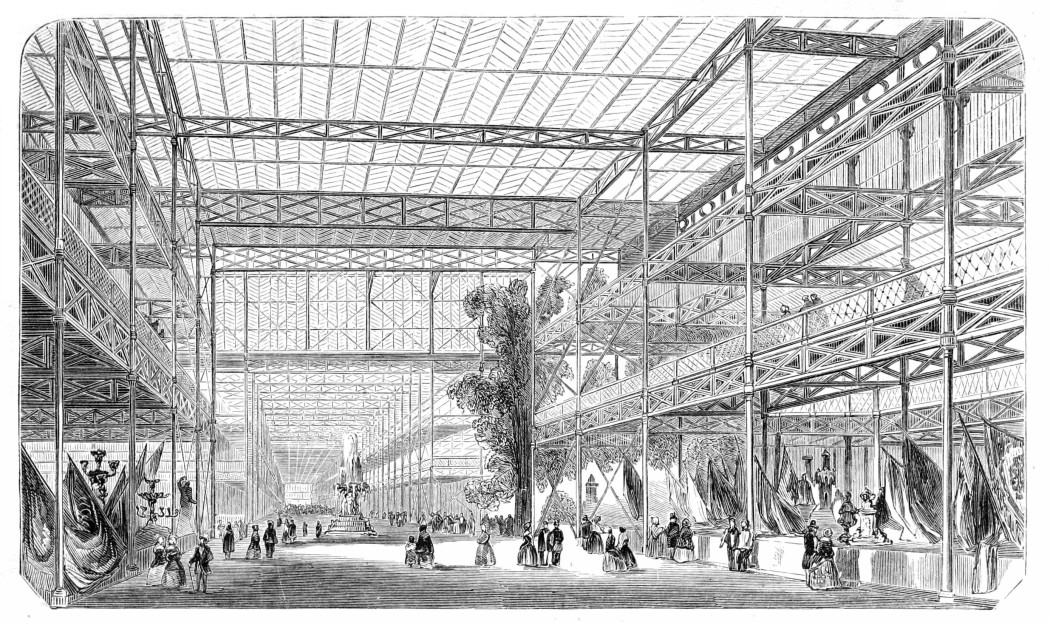

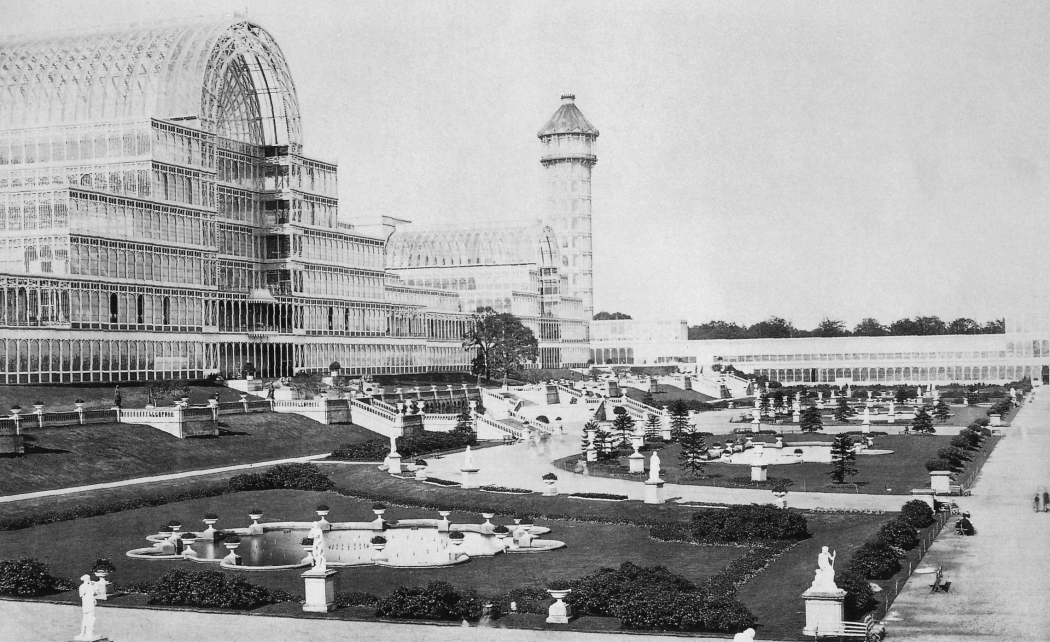

The Crystal Palace at The Great Exhibition, London, 1851

Joseph Paxton’s iron and glass structure left a lasting impression on the millions of visitors to the Great Exhibition, held in London’s Hyde Park in 1851. Though it was destroyed by a fire in 1936, it was imitated at several World’s Fairs beyond the Great Exhibition and deemed popular enough to be moved and remounted on the other side of the city before it met its fate.

The Crystal Palace at The Great Exhibition, London, 1851

Joseph Paxton’s iron and glass structure left a lasting impression on the millions of visitors to the Great Exhibition, held in London’s Hyde Park in 1851. Though it was destroyed by a fire in 1936, it was imitated at several World’s Fairs beyond the Great Exhibition and deemed popular enough to be moved and remounted on the other side of the city before it met its fate.

Photography: Paul Furst

Memorial Hall at the Centennial Exposition, Philadelphia, 1876

Philadelphia’s Memorial Hall has been a mainstay of the city’s cultural scene since it was built to house an art museum during the 1876 Centennial Exposition. Now home to a children’s museum that opened in 2008, the Beaux-Arts style building illustrates how World’s Fair sites can be continually repurposed over multiple generations.

Memorial Hall at the Centennial Exposition, Philadelphia, 1876

Philadelphia’s Memorial Hall has been a mainstay of the city’s cultural scene since it was built to house an art museum during the 1876 Centennial Exposition. Now home to a children’s museum that opened in 2008, the Beaux-Arts style building illustrates how World’s Fair sites can be continually repurposed over multiple generations.

Photography: Centennial Photographic Co.

Photograph: Jack Boucher

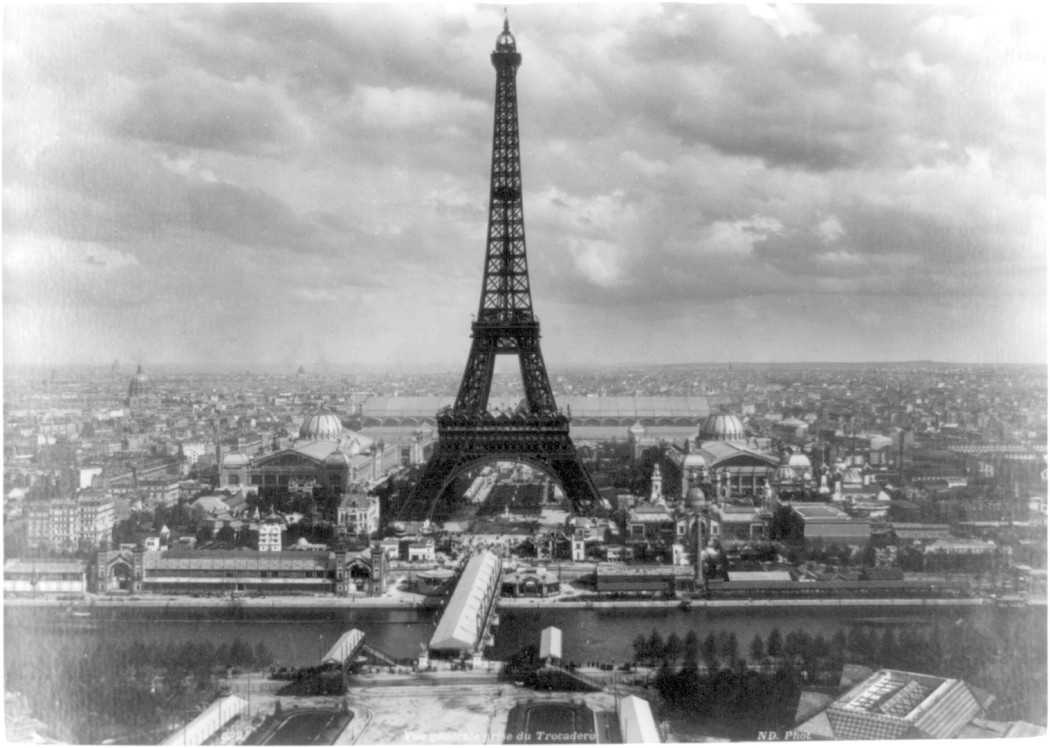

The Eiffel Tower at the Paris World’s Fair, 1889

At the time of its construction for the 1889 World’s Fair, the Eiffel Tower was the tallest structure in the world and, according to its creator Gustave Eiffel, a monument to the industrial and scientific achievements of the time. The fact that it is currently the planet’s most-visited paid monument suggests that people remain in awe of this era-defining engineering feat.

A view of the Paris Exposition in 1889.

The German Pavilion at the Barcelona International Exhibition, 1929

Mies van der Rohe’s German Pavilion for the 1929 Barcelona International Exhibition persists as a monument to minimalism that provides a counterpoint to the brash and overblown architecture typical of World Expos. It was rebuilt on its original site in 1986 and its precise combination of steel, glass and stone makes it a mecca for architectural tourists.

Photography: Magnus Mankse

The German Pavilion at the Barcelona International Exhibition, 1929

Mies van der Rohe’s German Pavilion for the 1929 Barcelona International Exhibition persists as a monument to minimalism that provides a counterpoint to the brash and overblown architecture typical of World Expos. It was rebuilt on its original site in 1986 and its precise combination of steel, glass and stone makes it a mecca for architectural tourists.

Photography: Malouette

The Atomium at Expo ‘58, Brussels, 1958

The Atomium looms over the Belgian capital like a gleaming totem that seems to belong to both the past and the future. Nine steel balls connected by navigable tubes are modelled on the cellular structure of an iron crystal, perfectly encapsulating Expo 58’s focus on scientific and technological progress.

Photography: Mike Cattle

The Atomium at Expo ‘58, Brussels, 1958

The Atomium looms over the Belgian capital like a gleaming totem that seems to belong to both the past and the future. Nine steel balls connected by navigable tubes are modelled on the cellular structure of an iron crystal, perfectly encapsulating Expo 58’s focus on scientific and technological progress.

Photography: H Krumnack

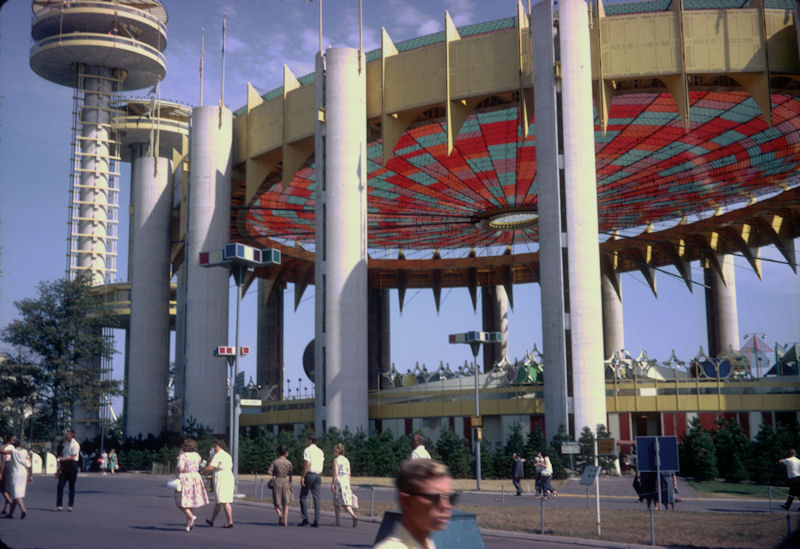

New York State Pavilion pictured in 1964

New York State Pavilion at New York’s World’s Fair, 1964

Philip Johnson’s New York State Pavilion is one of few remaining structures at the Flushing Meadows site of the 1964/65 Expo. Earlier this year, a $3 million donation enabled the repainting of the rusty crown surrounding the Tent of Tomorrow, which originally supported the world’s largest cable suspension roof and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Photography: Brendan Crain

The US Pavilion at Expo 67, Montreal, 1967

A masterpiece of modern engineering, the giant geodesic dome created by Richard Buckminster-Fuller to house the United States pavilion at Expo 67 in Montreal was repurposed in 1995 to accommodate a museum dedicated to the environment. It’s an appropriate fate for a structure designed by a pioneer of sustainable thinking.

Photography: Philipp Hienstorfer

The US Pavilion at Expo 67, Montreal, 1967

A masterpiece of modern engineering, the giant geodesic dome created by Richard Buckminster-Fuller to house the United States pavilion at Expo 67 in Montreal was repurposed in 1995 to accommodate a museum dedicated to the environment. It’s an appropriate fate for a structure designed by a pioneer of sustainable thinking.

Photography: Guilhermeduartegarcia

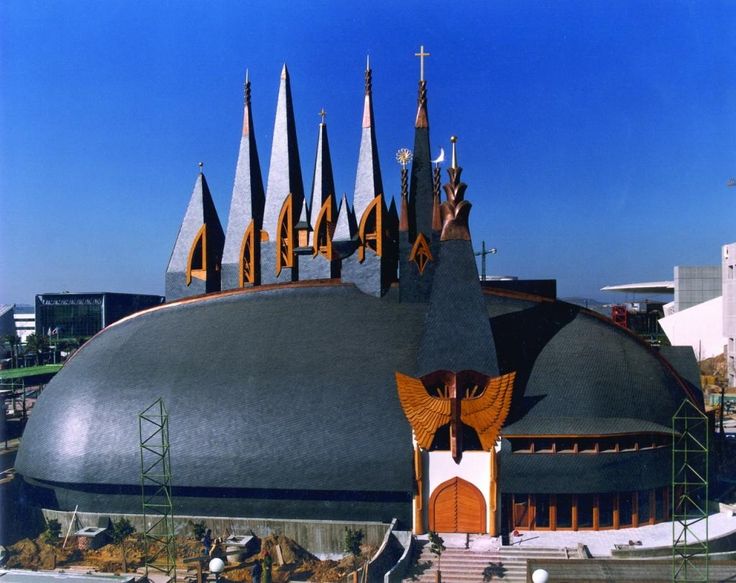

The Hungarian pavilion at Seville Expo 1992

The Hungarian pavilion designed by Budapest-born naturalist architect Imre Makovecz for the 1992 Seville Expo is probably one of the most fantastical structures ever seen at an Expo. Featuring a scaly roof and turrets topped with religious icons, it is regarded as a seminal piece of timber architecture but is currently derelict and reportedly on the market for $1.1 million.

The China pavilion at 2010 World Expo Shanghai

The China pavilion at the 2010 World Expo Shanghai was, characteristically, the largest national pavilion at the event and the biggest display in the history of World Expos. In 2012 it reopened as a museum dedicated to modern Chinese art, with its total exhibition area of approximately 64,000 square metres, making it the largest art museum in Asia.

Photography: David Xiao Da Shan

The China pavilion at 2010 World Expo Shanghai

The China pavilion at the 2010 World Expo Shanghai was, characteristically, the largest national pavilion at the event and the biggest display in the history of World Expos. In 2012 it reopened as a museum dedicated to modern Chinese art, with its total exhibition area of approximately 64,000 square metres, making it the largest art museum in Asia.

Photography: David Xiao Da Shan

The British pavilion at Expo Milano 2015

The 2015 British pavilion was designed by Wolfgang Buttress to draw attention to the plight of the honey bee. The artist created a multi-sensory experience featuring sights, sounds and smells associated with apiarian ecology. Some of its landscape elements are being reused at new sites in Milan, while talks are under way to re-erect the demountable pavilion elsewhere. A soundscape created for the Expo will be released as an album in February 2016.

Photography: Mark Haddon

The British pavilion at Expo Milano 2015

The 2015 British pavilion was designed by Wolfgang Buttress to draw attention to the plight of the honey bee. The artist created a multi-sensory experience featuring sights, sounds and smells associated with apiarian ecology. Some of its landscape elements are being reused at new sites in Milan, while talks are under way to re-erect the demountable pavilion elsewhere. A soundscape created for the Expo will be released as an album in February 2016.

Photography: Mark Haddon