Wooden and concrete homes by Skälsö Arkitekter are nestled within the landscape of Bungenäs

They are joined by bunkers and other military buildings, many of which have been repurposed as houses

The kilns and limestone barn of Bungenäs

Built in 1910, the barn was taken over by the military in the 60s before being abandoned. Skälsö have lightly renovated the building, turning it into a restaurant and art gallery (currently closed for the winter)

As well as hosting exhibitions featuring top Swedish artists, the barn also doubles as a space for concerts

Visitors have to leave their cars at the gate and explore the island on foot or by bicycle

Building no.8 was once a military bunker – now a private home

Skälsö dug out a sunken courtyard and created a hole in the bunker’s concrete walls, now filled in with glass. The sheltered courtyard forms a micro-climate, where the snow melts first on Bungenäs

All renovations are done with a light touch, so that the bones of the buildings can still be seen

The dining area is the perfect place from which to admire the views

Nyströms café was once a commissary for workers of Bungenas Kalkbrott, a defunct limestone quarry

The original wood panelling inside the coffee shop has been retained

Different planning rules apply to different zones of the peninsular, resulting in a range of architectural styles. All take cues from the landscape

This 1940s former canteen was transformed into Bungenäs Matsal, a fine dining restaurant, by Skälsö Arkitekter

Bungenäs Matsal, pictured ahead of the restoration work

The restaurant overlooks the sea

Bungenäs Matsal also doubles as a hotel

Where to snooze under the stars during summer months

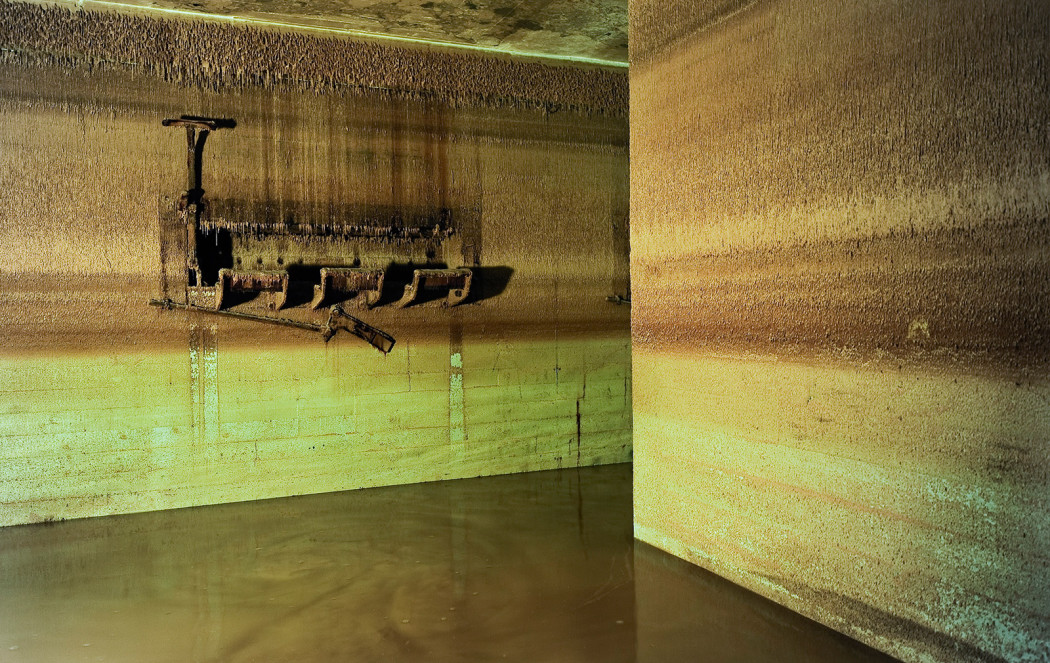

The bunkers of Bungenäs are at varying stages of transformation. Pictured is no. 104

The skylight of bunker no. 104

Building no. 85 is perched on Bungenäs’ highest plateau, with views of the Baltic Sea on three sides and the large quarry to the west. The house and courtyard form a perfect square. Its grid of pine slats will eventually be taken over by vegetation, which will camouflage the building in the landscape. Photography: Magdalena Björnsdotter

The living area opens out onto the courtyard. Photography: Magdalena Björnsdotter

The kitchen of the open-plan building. Photography: Magdalena Björnsdotter

Large windows frame the views. Photography: Magdalena Björnsdotter

Beneath this mound is another military bunker

The partly transformed bunker

Littorina 7 is another of the island’s private homes. The building’s L-shaped plan creates a sheltered courtyard, overlooking the sea

The building is clad in untreated pine, which will eventually turn grey and blend in with the landscape

The interior of Littorina 7

So far, a dozen or so houses have been built, while an additional five to ten summer cottages are currently being constructed

Many plot owners hire Skälsö to design their houses – such as this property – but they are free to choose whomever they wish

An abundance of wood gives this house a feeling of warmth

One of the larger contemporary structures on the peninsula

Interior spaces are kept simple to ensure nothing detracts from the views

Sheltered terraces protect residents from the elements

A remote peninsula on the Swedish island of Gotland has become an unlikely tourist destination.

Bungenäs – a barren but beautiful strip of land on its north-eastern tip – had been off limits to the public for over 50 years. Now scores of visitors journey to the area, tipped off by social media and word of mouth.

These pilgrims are drawn by the new restaurants, cultural venues, and startling contemporary architecture that pepper the peninsula’s Game of Thrones-like scenery.

Bungenäs’ reincarnation began in 2007, when entrepreneur Joachim Kuylenstierna acquired the 160-hectare site from the Swedish army. It had used the area for a military training base since 1963, leaving behind a trail of abandoned bunkers and crumbling buildings. Prior to that, Bungenäs had been exploited as a limestone quarry between 1910 and 1960.

‘My father was part of the military here’, Kuylenstierna told Swedish newspaper Expressen. ‘I’ve always dreamt of doing something [on Bungenäs].’

Kuylenstierna enlisted Gotland-based architectural firm Skälsö Arkitekter (of which he is a silent partner) to develop a master plan for the entire area in 2010. Retaining the site’s unique history and character was paramount.

‘We don’t design and build buildings – we work with the landscape and the existing constructions to create structures that are formed after their surroundings,’ says Lisa Ekström, an architect at Skälsö. ‘We’re not the least interested in creating “boxes” on the ground.’

A critical part in the creating of the close-knit, freethinking community that Bungenäs has become is the banning of all cars. These are left at the fence, upon which visitors must explore the land by foot or bike (the army’s old bikes are loaned free of charge).

A three-kilometre-long excursion takes visitors through an art gallery and restaurant housed in a former limestone barn, an eatery inside a 1940s building, and a café created within a former self-service store. Scattered along the many paths are a dozen or so vacation houses, carefully embedded in their surroundings, while an additional five to ten summer cottages are currently being constructed. Many involve the adaptive reuse of bunkers buried within the undergrowth.

Short-term visitors are encouraged to stay the night in one of the six available rooms above the restaurant, Bungenäs Matsal.

We spoke to Lisa Ekström about growing and safeguarding this unique Swedish community.

One of the original details that you’ve chosen to preserve is a fence that surrounds the entire area. Why was that important?

The army originally put it up, and Joachim Kuylenstierna had the vision of keeping cars out of Bungenäs. Retaining the fence allowed for that, and for having livestock graze freely on the peninsula. The entire area is open to the public 24-7 so the fence is not there to exclude anyone. Instead, the fence contributes to the area’s uniqueness and seclusion.

It has taken three years of Skälsö’s time to create the master plan for the area. What has made it so complex?

When Joachim Kuylenstierna purchased the area from the army, he also hired architects to work on the zoning plan in collaboration with Region Gotland. Each plot of land is specifically laid-out and, in turn, has its very own zoning plan. The peninsula was also divided into different regions with their own defined type of nature, which required different types of structures.

We created building regulations, complete with information on materials and techniques and ways of construction for each individual zone. Every single regulation is based around the existing landscape.

The plots of land are available for between 600,000 and 3.5 million Swedish kronor. What is the process for someone who wishes to purchase a plot?

Before one can even go ahead and apply for a building permit from the local government, the floor plan of the house has to be approved by the Bungenäs design committee. This comprises one representative of the Bungenäs lime quarry, an architect at Skälsö, a person living in the area and a couple of creatives with strong ties to the local community.

Are there any precedents for this project?

We studied The Sea Ranch in California closely. It’s a community where a number of architects have worked on housing that is completely adapted to the surrounding nature. They have also appointed a design committee to oversee what’s being built. We met with one of The Sea Ranch’s founding architects, Richard Whitaker, who has also visited Bungenäs.

What have been the chief challenges in the conception of the Bungenäs community?

The hard part hasn’t been the conception itself – the real challenge lies ahead, in retaining the original vision for the area. Coming up with the idea is easy, but to carry it out is where the real work lies. It is a constant tussle. We find ourselves fighting for the survival of the pine trees on a daily basis.

What are the winters like, in this remote part of Sweden?

I personally find Bungenäs at its very best in the winter. It is completely void of people, and the landscape is completely barren. It is stunning – and pitch-black during most hours of the day.