Across two gallery spaces on London’s Duke Street, Thomas Dane gallery’s newly opened exhibitions explore the interplay of art and architecture.

In the glass-fronted, white cube space at No. 3, Office Kersten Geers and David Van Severen have installed a disorientating asymmetrical form that bisects the space, manipulating the flow of light and the way the eye travels around the gallery.

Hung on and around this form is a series by Luisa Lambri, in which the photographer better known for her architectural studies turns her camera on artworks by Donald Judd, Lygia Clark, Charlotte Posenke and Barbara Hepworth.

Lambri teases out the architectonic forms of these works, their scale concealed by the framing of the image. The highly polished reflective corners of Donald Judd’s ‘100 Untitled Works In Mill Aluminum’, 1982-1986, seen through Lambri’s lens could be details of a monumental Frank Gehry façade or a vacated grain silo.

![Untitled-[Stringed-Figure-(Curlew),-Version-II]](https://thespaces.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Untitled-Stringed-Figure-Curlew-Version-II.jpg)

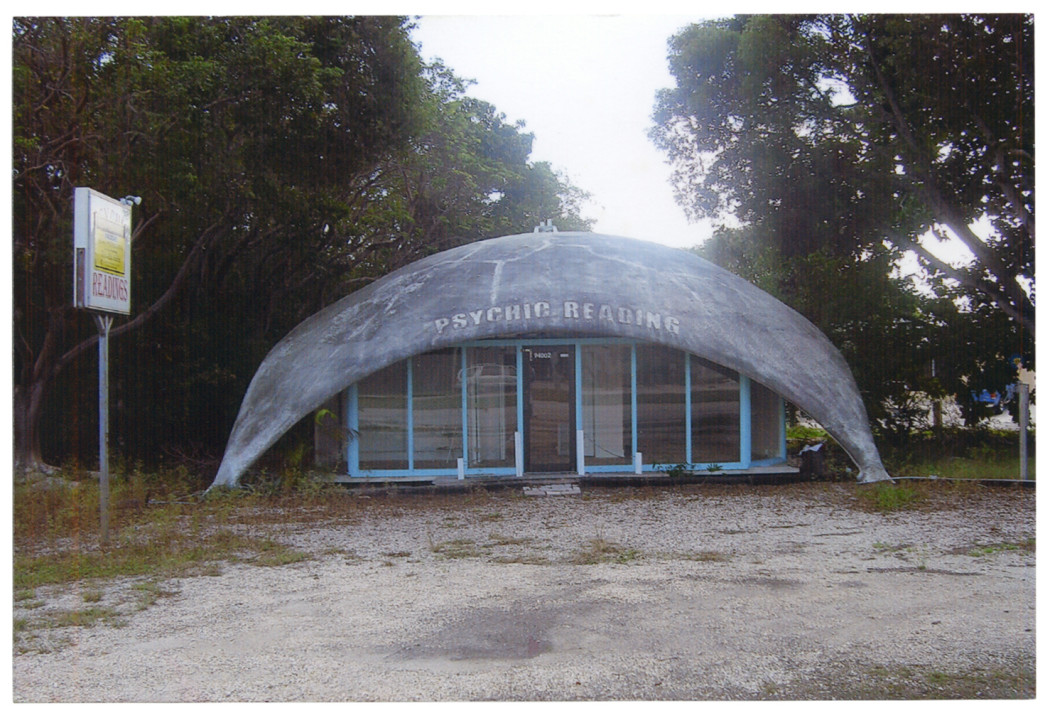

Much less polite is Blind Architecture, shown in the higgledy-piggledy 18th-century rooms on the first floor of No. 10. Here 20 artists and studios are shown responding to architecture in various scales and media. Some – such as Catherine Opie’s tiny, soft platinum print depicting a freeway intersection like fuzzy, folding limbs, and Rachel Whiteread’s rubber flooring slab that lolls in the gallery space like a giant amber tongue – eke out the corporeal in the built world.

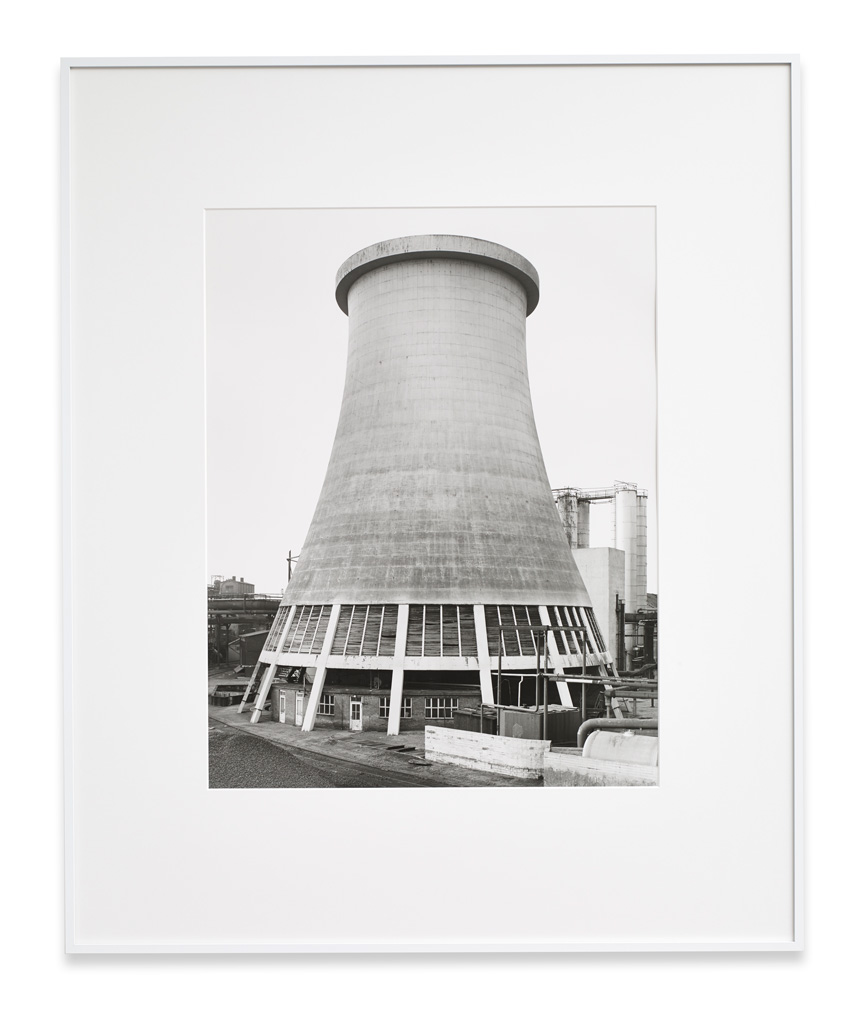

Hilla and Bernd Becher, ‘Cooling Tower, Luebeck-Herrenwyk, Germany 1983’

© Bernd + Hilla Becher

Hilla and Bernd Becher, ‘Tom Pudding Hoise, Goole, GB, 1997’

© Bernd + Hilla Becher

Hilla and Bernd Becher, ‘Tom Pudding Hoise, Goole, GB, 1997’

© Bernd + Hilla Becher

Hilla and Bernd Becher, ‘Cooling Tower, Geleen, Limburg, NL, 1968’

© Bernd + Hilla Becher

Rachel Whiteread, ‘Untitled (Amber Floor)’, 1993 rubber © Rachel Whiteread; Courtesy of the artist, Luhring Augustine, New York, Lorcan O’Neill, Rome, and Gagosian Gallery

‘Sao Paulo Station’. Eric Franck Fine Art for Geraldo de Barros

© Geraldo de Barros / Instituto Moreira Salles, Courtesy Eric Franck Fine Art

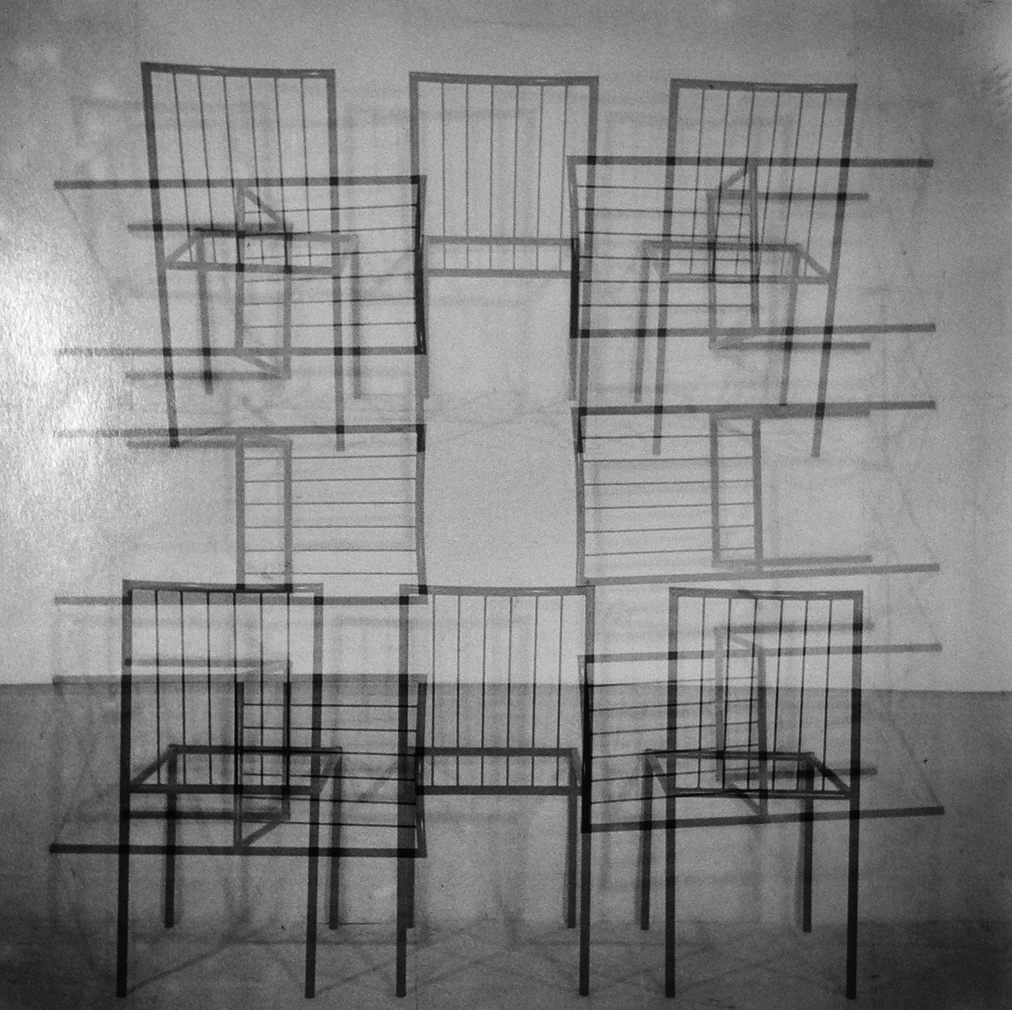

‘Chaises Unilabor’. Eric Franck Fine Art for Geraldo de Barros

© Geraldo de Barros / Instituto Moreira Salles, Courtesy Eric Franck Fine Art

Geraldo de Barros, ‘Hommage a Simeao’, 1950

Paula Cooper for Robert Grosvenor

© Robert Grosvenor. Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York

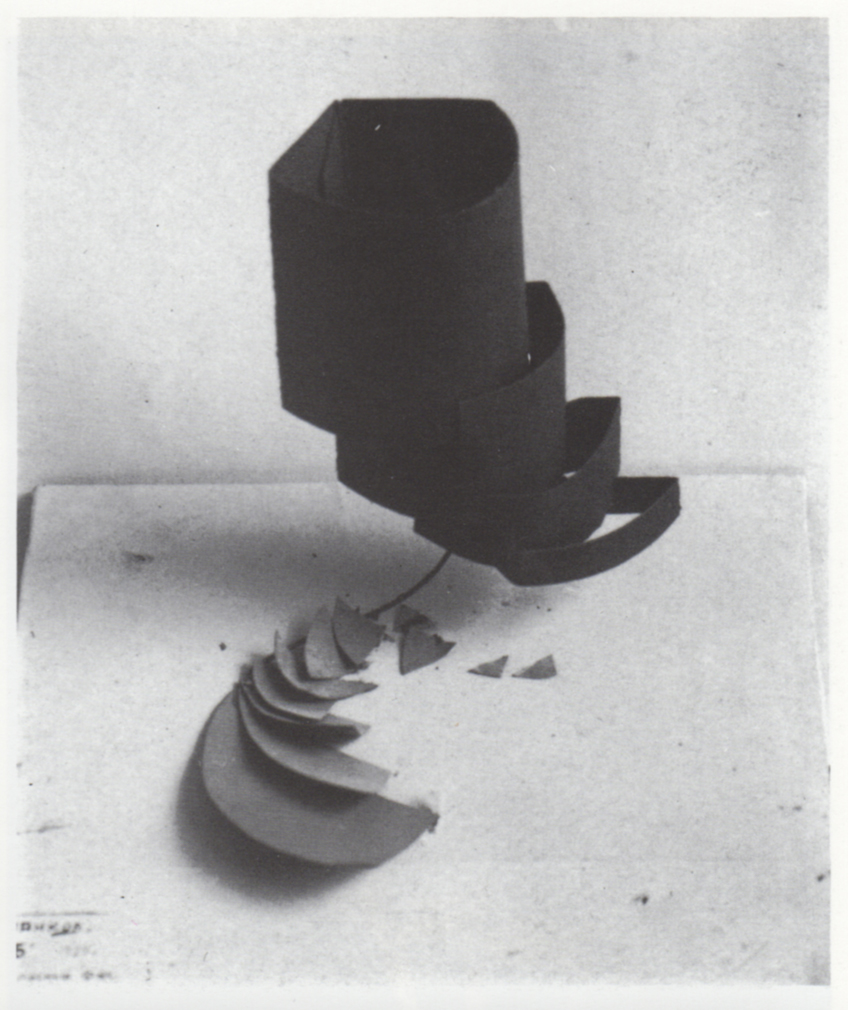

VKhUTEMAS WORKSHOPS, ‘Untitled’. Date unknown.

VKhUTEMAS WORKSHOPS, courtesy of Richard Saltoun Gallery

VKhUTEMAS WORKSHOPS, Vkhutemas IV-5-30, 1920s. Courtesy Richard Saltoun Gallery

Gabriel Serra

Courtesy of the artist and kurimanzutto, Mexico City Photo: Omar Luis Olguin

Talwar Gallery for Nasreen Mohamedi. Courtesy Talwar Gallery

Nasreen Mohmedi, ‘Untitled’, circa 1970s printed in 2003. Talwar Gallery for Nasreen Mohamedi

Courtesy Talwar Gallery

Elsewhere, architecture is mined for its sculptural forms, and sculptural forms for their suggestions of architecture. Of the former, four examples from Hilla and Bernd Becher’s career-long series of restrained formal studies of industrial structures stand out – taken between 1968 and 1997, they might have been photographed on the same day. Uncredited images from the Soviet VKhUTEMAS Workshops in the 1920s show small building-like sculptural forms – ‘blind’ as the title of the exhibition suggests, because unlike architectural models, they have no windows.

Architecture’s less grandiose aspect is captured in Gabriel Orozco’s photograph of an island of mucky debris accruing within a puddle, which offers an abject echo of the Manhattan skyline seen in the background.

Questions of utility, too, are evoked in Jean-Luc Moulène’s onyx rendering of a concrete tetrapod – a jack-shaped structure deployed in vast quantities around the world to prevent coastal erosion. It’s not beautiful, perhaps, but the tetrapod is a structure that defines our built environment just as much as the clean, glass-fronted box of the contemporary art gallery.