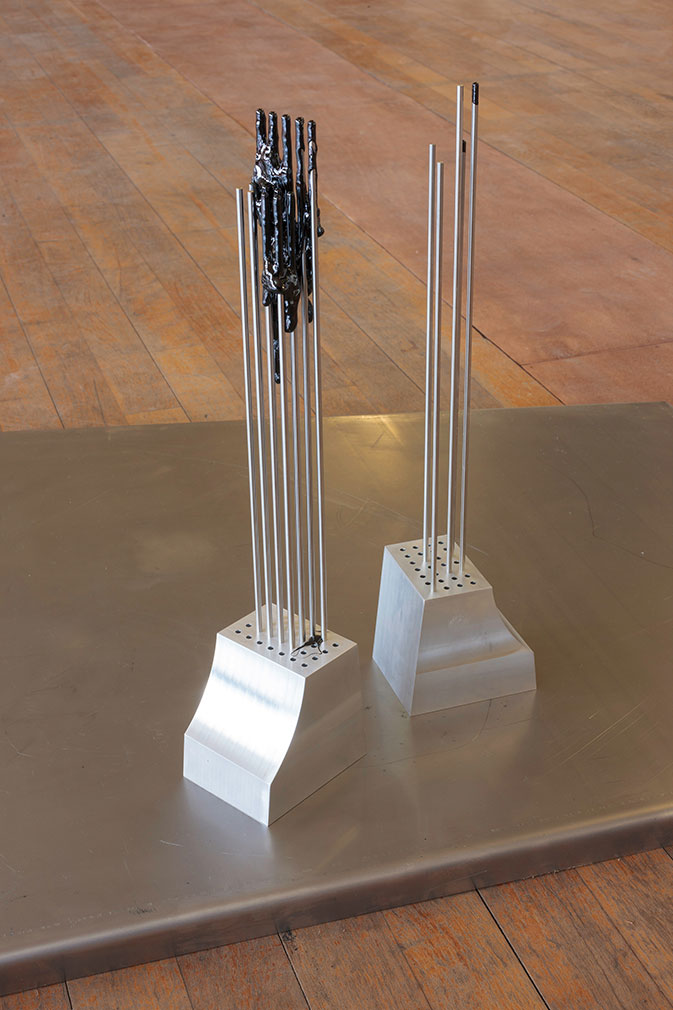

Installation view of Bright Bodies by Claire Barclay at Kelvin Hall

Installation view of Bright Bodies by Claire Barclay at Kelvin Hall

Installation view of Bright Bodies by Claire Barclay at Kelvin Hall

Installation view of Bright Bodies by Claire Barclay at Kelvin Hall

Claire Barclay’s pungent installation responding to Glasgow’s dilapidated Kelvin Hall deploys materials for their evocative qualities. Rubber, leather, steel and coal tar each lend their particular texture and smell to evoke aspects of the building’s history.

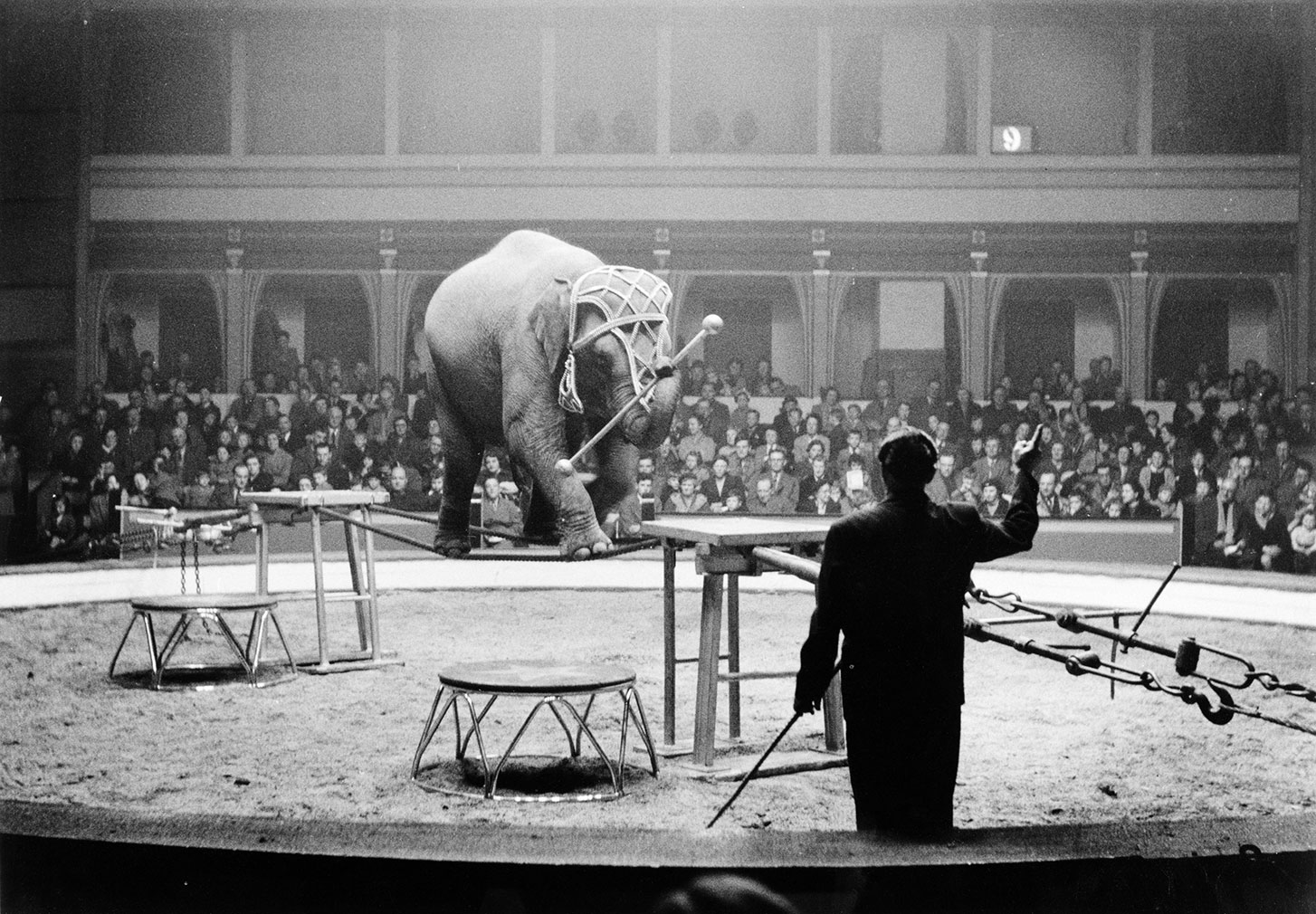

Dominated by scorched and fleshy tones of red and black, Bright Bodies is drawn out across the first floor front section of the once-grand building. Built as an events space in the 1920s, Kelvin Hall went on to house the 1951 Exhibition of Industrial Power and has since been used as a concert and circus arena, sports hall and museum of transport.

Currently housing a pair of exhibitions for the Glasgow International Festival, the Hall is entering a renovation period. Paint peels off the stairwell in elongated leaves and daubed red letters restrict entry to areas beyond the shows.

Within Barclay’s installation space, reinstated chandeliers and sections of stained glass are reflected in a black mirror of coal tar, but the cavernous main hall of the building beyond is now stripped of such decorative folderols.

Barclay’s chosen materials are directly linked to the building’s history. ‘The steel, coal tar, soot, machined metal, canvas and rubber were each connected in more than one way to past uses of the Kelvin Hall,’ explains the artist, who has memories of the venue in various of its incarnations.

‘Rubber perhaps referencing sports equipment and motor show exhibits,’ she continues. ‘The steel cage structures suggest a mock coal-mine cage and other steel structures that were part of the 1951 exhibition.’ They’re also ‘similar to props used in the carnival and circus’.

Designed by Sir Basil Spence, the Exhibition of Industrial Power was held as part of the post-war Festival of Britain and focused on the electricity. Offering sections dedicated to water and coal – evoked through a vast sculpted coalface created by Thomas Whalen, and a 20,000-gallon waterfall – the exhibition concluded with the Hall of the Future in which a ‘lightning machine’ was used to illustrate the theory of nuclear fission.

Human labour, too, was celebrated – the coalface was depicted complete with a ‘cage’ operated by real miners. Sixty-five years later, their physical labour also informs Barclay’s installation. The straining fleshiness of the stretched rubber and leather in Bright Bodies and the sagging, lung-like sacks smeared with soot suggest a dissection scene as much as a meditation on architectural history.

It took three weeks working in the space for Barclay to achieve the desired balance between the building and the work, many elements of which were made in situ in direct response to ‘the fabric of the building and the industrial heritage from which it was born’. In co-opting the decorative grandeur of the building, Barclay examines ‘how the quality of craftsmanship masks the raw brutal nature of industrial production, but also conserves evidence of human endeavour and labour.’