There was a distinct whiff of déjà vu in the air at Frieze London this year.

Much to the distress of those who consider the 1990s the very recent past, a section of the fair was dedicated to revisiting the decade, specifically a selection of exhibitions that have had a lasting impact on contemporary art.

One of the highlights was the 1:1 recreation of Wolfgang Tillmans’ first show, held in January 1993 in a small space behind a bookshop owned by the gallerist Daniel Buchholz’s father.

The act of recreation is one that artists have deployed in a variety of ways over the years. Here are some of our favourites, from the cinematic and the hypothetical, to the vividly literal.

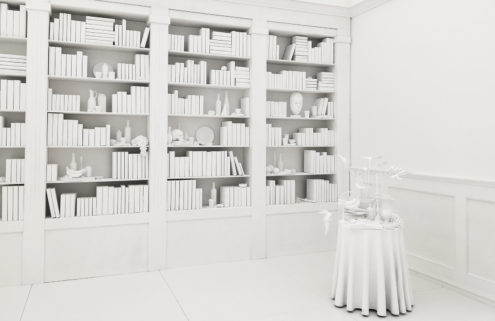

Helly Nahmad – The Collector, 2014

Upending the white-box conventions of an art fair stand, Helly Nahmad placed his wares for Frieze Masters 2014 into the context of an imaginary art collector’s Parisian apartment. Visitors could wander through the constructed reality, set in 1968, which was designed by Robin Brown and Anna Pank. Pieces such as Giacometti’s emaciated sculptures and slashed works by Lucio Fontana sat next to revolutionary posters from the student protests of that year and stacks of contemporary art magazines, with Miles Davis singing overhead. The Collector himself, unseen and of course fictional, acted as the uniting force between the pieces.

Jeremy Deller – ‘Open Bedroom’, Joy in People, 2012

In 1993 Jeremy Deller was living at home, wanting to show his work, but not quite sure how to go about it. So he took advantage of his parents going on holiday to stage an exhibition in their house. Pieces were installed everywhere there was wall space, from the sitting room – replacing his parents’ artworks – to the bathroom, downstairs loo and his bedroom. Nearly two decades on, as part of his first retrospective exhibition at London’s Hayward Gallery, Deller recreated his bedroom exactly as it was for his unconventional inaugural show.

Philippe Parreno – Marilyn, 2012

In 2012, Philippe Parreno reanimated Marilyn Monroe in a emotional video work set inside the Waldorf Astoria hotel. Precisely recreating the three-room suite that was the actress’s home for 8 months in 1955, Parreno’s work imagines Monroe crossing the room and sitting down to write a letter. As robots replicate her voice and handwriting, swerving camerawork evokes her rising anxiety, which is heightened by the overly ordered room and a telephone that rings incessantly yet goes unanswered. As it ends, the camera pans back to show the suite empty, clearly a set; Marilyn’s reality revealed as a perpetual construct.

Robert Morris – Bodymotionspacesthings, 1971/2009

Rejecting the common experience of visitor looking at art, Robert Morris invited visitors to participate in Tate gallery’s first ever interactive show in 1971. He constructed an oversized sculptural playground made up of giant beams, ropes, tunnels and ramps that gave ‘an opportunity for people… to become aware of their own bodies, gravity, effort, fatigue, their bodies under different conditions.’

Morris could not have foreseen its popularity, however. Within four days the show was closed down because Tate staff ‘were not able to cope with the frantic means of emotional release that the exhibition became. An orderly pandemonium was expected, but pandemonium broke out.’

Unperturbed, 38 years later Tate decided to try again, working with contemporary materials and Morris’ original plans to recreate the exhibition to a similarly exuberant – but this time not site-closing – reception in the Turbine Hall.

Michael Landy – Semi-Detached, 2004

Sixty-two Kingswood Road, in all its pebble-dashed, net curtained glory, was an unexpected sight in the hallowed halls of Tate Britain’s Duveen Galleries in 2004. Closer inspection revealed it to be a recreation of the exterior of artist Michael Landy’s old home in Ilford, where the family was living in 1977 when his father John suffered a life changing accident. Semi-Detached was a son’s portrait, expressed through architecture, of a father’s life diminished by ill health and isolation. The exterior façades, sublime in their ordinariness, were painstakingly recreated down to the last rusty nail, while the interior was projected cinematically, in two films that trailed John Landy through crumbling rooms lined with dust and detritus.

Read next: Joan Miro’s art studio comes to London