Prolific use of the term ‘design’ is relatively recent thing, which dates to the 1990s when ‘design thinking’ began to be applied in business. If Deyan Sudjic has his way, it will become even more widespread. The director of London’s Design Museum said recently that he hopes the new premises in Kensington will do for design what Tate Modern did for art after its opening in 2000.

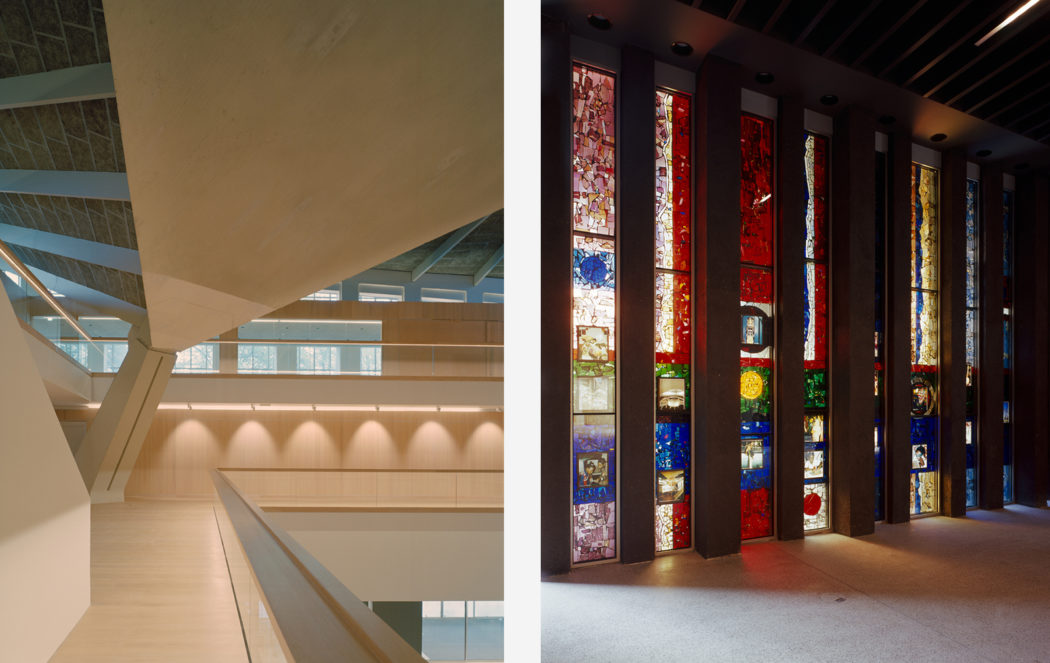

Following an £83 million transformation of the 1960s Commonwealth Institute by John Pawson, the Design Museum will open on 24 November. The volume of space will be massively increased to 10,000 sq metres, offering two large exhibition halls, a permanent display for the collection, a café/restaurant, education and events spaces and a members’ room. The Design Museum aspires to attract 650,000 visitors a year compared to the average attendance of 200,000 at the previous building in Shad Thames.

Photography: Hélène Binet

Photography: Hélène Binet

Photography: Hélène Binet

Photography: Hélène Binet

Photography: Hélène Binet

Photography: Hélène Binet

It’s inspiring to see such an ambitious project get off the ground, and the hope that this could bring design centre stage of public debate is exciting. One imagines a culture shift that might put the UK on an equal footing with Scandinavia in terms of the public appreciation of design.

But finally getting Brits to ‘chuck out the chintz’ is not quite what Sudjic and his team have in mind: discussing the aesthetic value of design is just a small part of their ambition. The director and his team are setting out to explore the meaning, cultural and political significance of design.

Says Sudjic: ‘It’s all very well to look at a smartphone in terms of how beautifully the edge is detailed and the scratch-proofness of the glass, but a more important question is, has it abolished the idea of privacy?’

The museum’s chief curator Justin McGuirk says the programme will act as a lens for looking at the world: ‘I still think a majority of people come to a design museum to see chairs and cutlery and products. And while of course those things will always be here, I think there is a bigger conversation to be had, which is about how we think about the world.’

Design has always been grounded in the ‘real’ world, and arguably makes a better lens for looking at it than art. There is of course a commercial side to the art world, but it is not at its service in the way that design traditionally has been. Until recently, terms such as industrial design and commercial art (design for advertising and books) were much more widespread and conveyed the close relationship of design to production, trade and commerce.

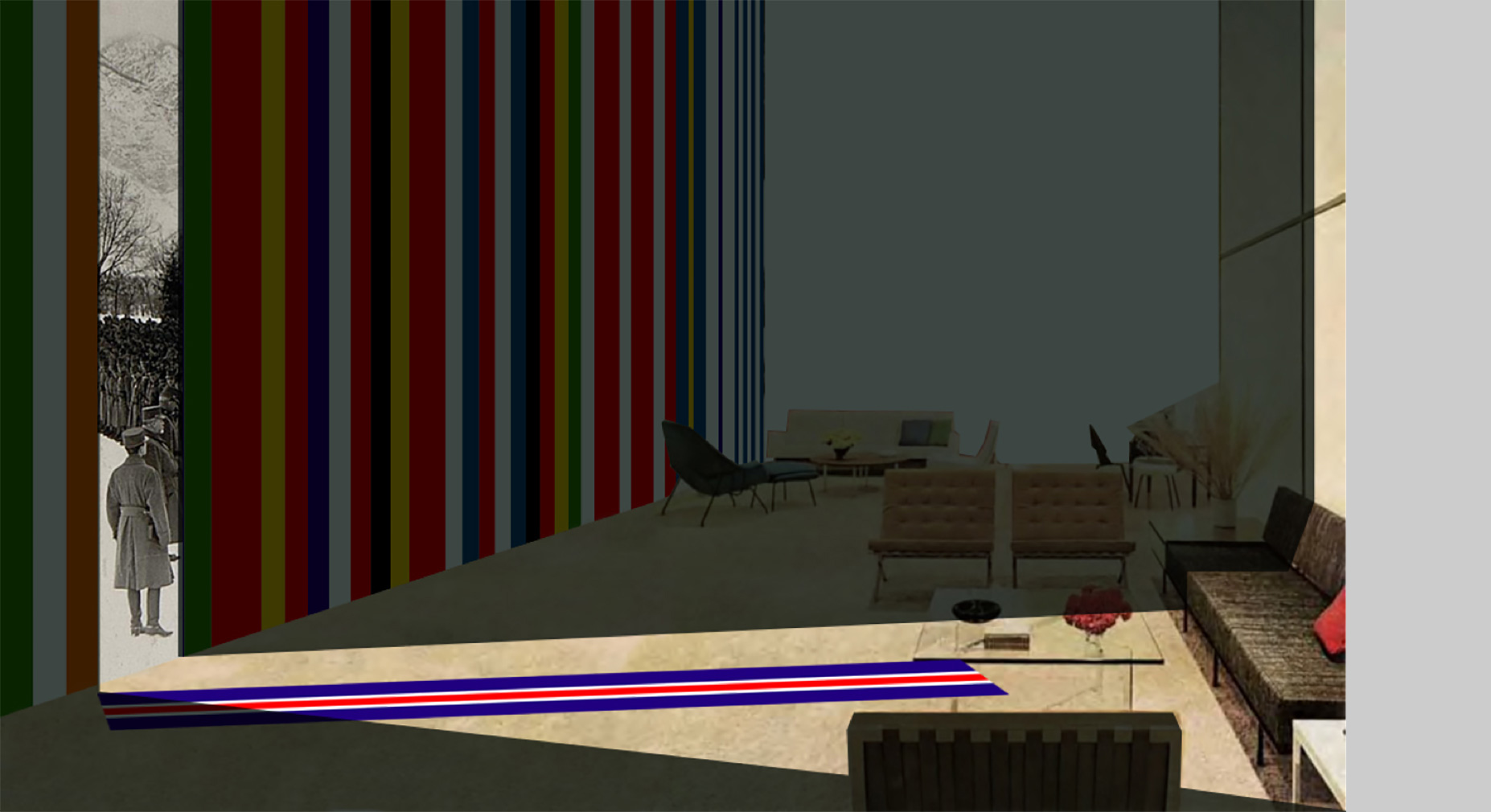

Visiting the new Design Museum ahead of its opening, one is very aware of the presence and influence of the market economy. This isn’t just because your first awareness of the museum is its shop on Kensington High Street, but because you have to walk through a development of luxury apartments, complete with security barriers and CCTV cameras, to get to the museum entrance. Adopting McGuirk and Sudjic’s approach, the visitor will be ‘de-coding’ these signifiers and getting an insight to the relationship between public and private, culture and commerce.

In fact, the Design Museum has been the beneficiary of a rather incredible planning deal between the developer, Chelsfield, and the local authority, The Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea. In return for building three blocks of luxury flats (without the usual requirement for affordable housing) designed by OMA, the developer has given the building to the Design Museum for 175 years and contributed £20 million towards the renovations.

Such a deal illustrates the close relationship between commerce and culture, and the fluid boundaries between public and private in today’s world. Yet, despite the inextricable links between the museum and the world of property development, there is a still a sense that cultural debate driven by a museum is independent of, and superior to, the principles and concerns of commerce.

Sudjic has commented that museums are replacing design magazines as the vehicles for critical dialogue (no coincidence he and McGuirk are both former journalists). But being critical these days often takes the somewhat predictable form of promoting sustainability, moralising against the market, or being politically provocative, as the Design Museum has attempted to be through its Designs of the Year awards.

I have reservations about the location of the luxury flats in front of the museum, blocking the view of it from the High Street, and seeming to place it in a secondary position. But I embrace the possibility that the new Design Museum might adopt an approach that is perhaps more honest about design and its own relationship with commerce.

Perhaps by creating open dialogue and debate, it might even help us reach a position where society can be more comfortable with the idea of economic growth and development – and not simply take refuge in the ‘safe’ space of culture.