Battersea Power Station might be a hive of activity once more, with architecture’s A-list turning the building and surrounds into a new urban precinct. But Sir Giles Gilbert Scott’s brick behemoth is far from the only vestige of London’s industrial heydey.

Its younger sibling – Bankside Power Station – was famously turned into art powerhouse Tate Modern by Herzog & de Meuron back in 2000. And beyond this, there are temples to industry aplenty, from art deco factories to gas holders, in varying states of revival or decay.

In King’s Cross, for example, coal yards are being turned into retail spaces, the Granary Building is now home to Central Saint Martins art school, and the Victorian gas holders are being turned into a public park and flats. Retaining these industrials structures is a core part of the developer’s strategy. ‘Without the historic buildings and story, the 67-acre site would have had no context from which to evolve the master plan,’ says Argent director Tom Goodall.

Many of the city’s industrial buildings – built in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, when industry was booming and labour came cheap – are embellished with elaborate craftsmanship. Marble floors and columned facades were standard specs for factories in the 1930s. Add to this large floor plates and its easy to spot their potential for adaptive reuse.

These buildings have endless possibilities thanks to their sheer scale: they could host everything from art studios, workshops and tech hubs to indoor markets and events spaces – or all of the above. Could they become the Roman forums of the 21st century; places where people can eat, work and play?

Perhaps, but these very proportions are also the biggest redevelopment challenge. The gargantuan scale of Grade II-listed Battersea Power Station saw many revival attempts stall and its current developers have published an entire book on ‘placemaking’ in their effort to create a new urban neighbourhood that’s alive at all hours of the day.

Where there is no English Heritage listing, demolition is often the cheaper alternative. But these historic structures have a value that’s not necessarily monetary. Says Goodall: ‘To ignore London’s past, bulldoze everything, and build a new piece of city would ignore everything which makes London so unique.’

Here, we see what’s happening to nine icons of London’s industrial architecture that have been saved from the wrecking ball.

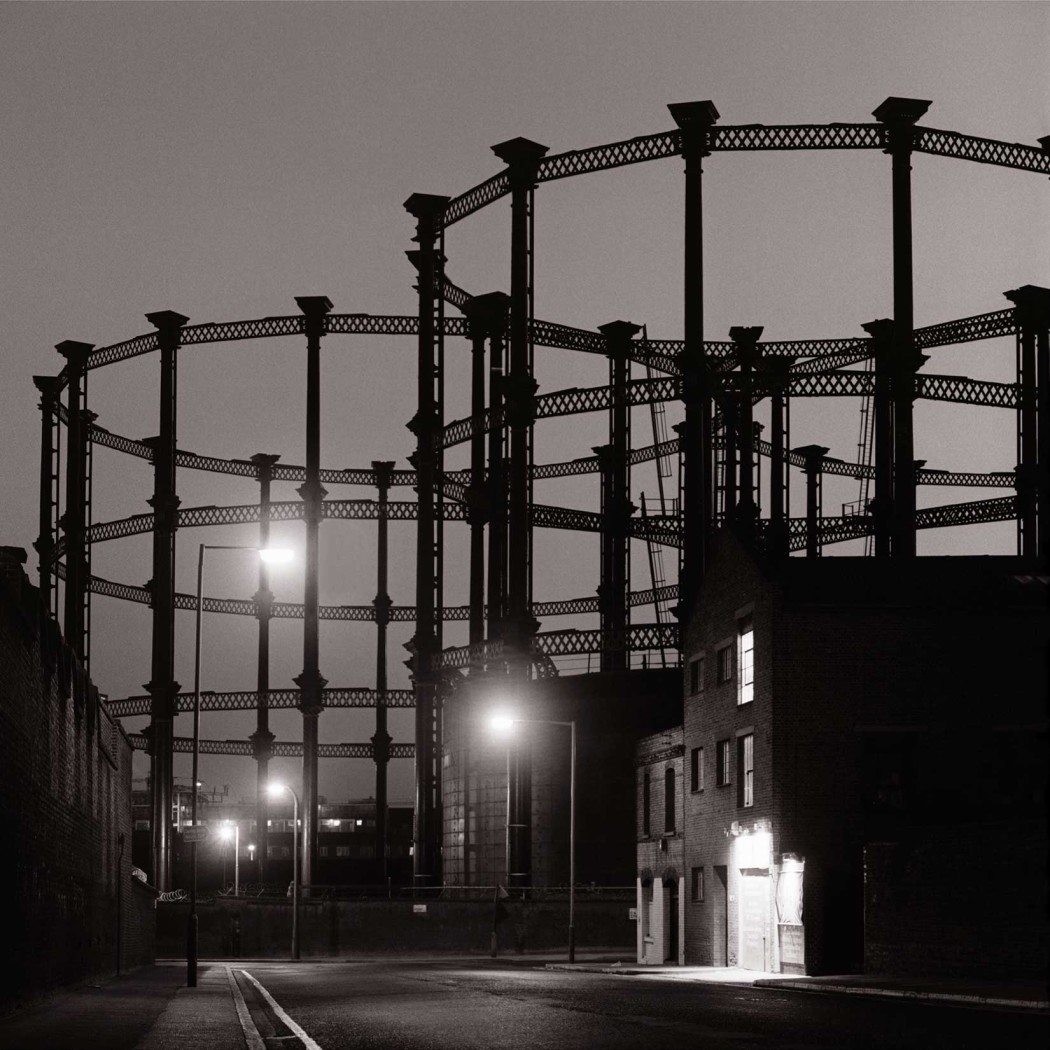

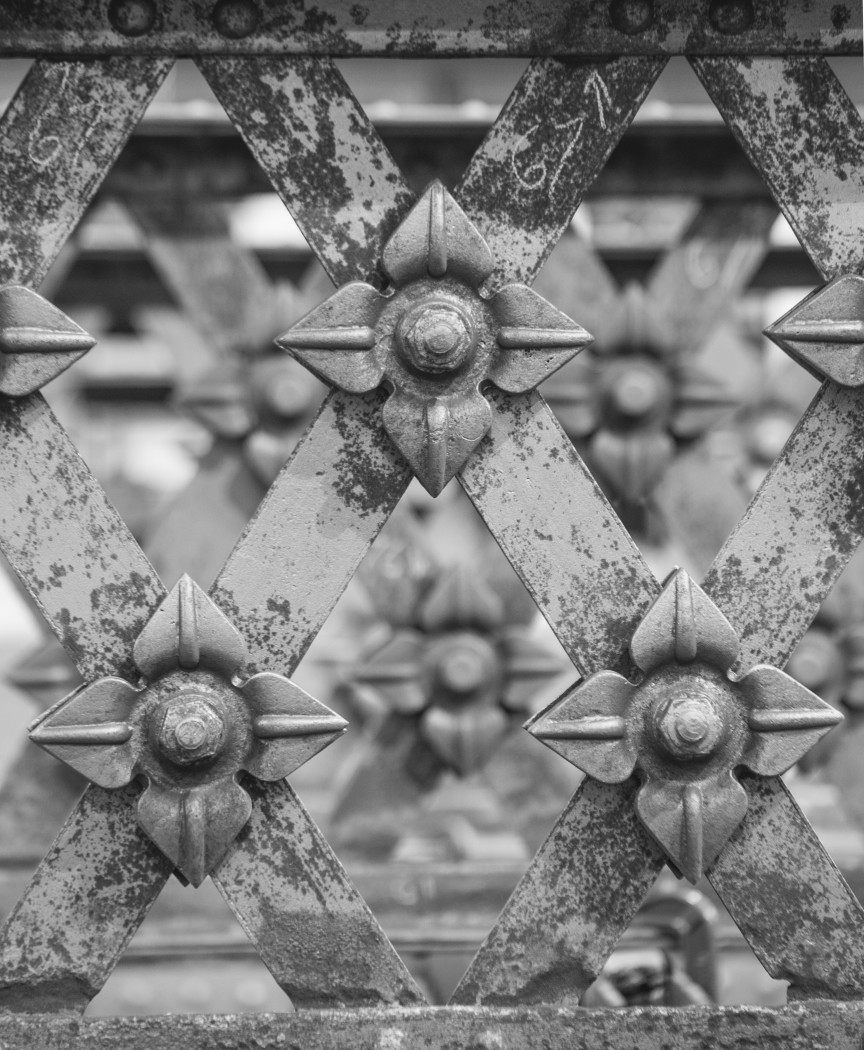

King’s Cross gas holders: All but a handful of the UK’s gas holders are now obsolete. While most of these sentinels of the country’s industrial age are being dismantled by the National Grid (including those in Battersea), some of London’s finest will stubbornly remain. The elaborate cast iron frames of the Grade II-listed ‘Siamese Triplets’ – a trio of King’s Cross gasometers, conjoined by a central spine – are being restored as part of Argent’s development master plan for the area, their wrought iron, riveted lattice girders carefully repaired. Meanwhile, Wilkinson Eyre Architects have drawn up plans to turn the 1860s gasometers into flats, complete with roof gardens, overlooking the canal. The apartments – featuring interiors by Jonathan Tuckey – will go on sale in 2016 and are scheduled for completion in 2017. Interest can be registered at Gasholderslondon.co.uk. Photography: John Heseltine.

King’s Cross gas holders: The wrought iron girders of the Siamese Triplets are currently being restored in Yorkshire ahead of their transformation into flats.

King’s Cross gas holders: Bell Phillips Architects won planning permission last year for its competition-winning scheme to turn Gasholder No. 8 into a public park. At 270,000 sq m, the 1950s structure is the largest gas holder on the King’s Cross site.

King’s Cross gas holders: A rendering of the public park in Gasholder No. 8, which will incorporate stainless steel canopy for shelter. ‘Gasholder No.8 provides a tangible connection with the site’s industrial heritage and this spectacular new space will give members of the public a dramatic new perspective of the historic structure,’ says architect Hari Phillips. The park will open in October 2015.

Gillette Factory, Brentford: Standing proud at the end of Great West Road’s ‘Golden Mile’ of classic 1930s industrial buildings, the Gillette razor blade factory was designed by Sir Banister Fletcher in 1937 and only ceased production in 2006. It is the largest surviving structure on the Golden Mile, which includes Wallis, Gilbert & Partners’ Wallis House – recently turned into flats and offices by Assael Architects. Planning permission was granted to turn the building into a hotel and office spaces but work was halted during the financial crash. Sold in 2013, it has since been used as a film location for Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy and 24, among others. Last year Hounslow council announced a master plan for bringing the shine back to the Golden Mile, including the building of 1,580 new homes and a new ‘Skyline’ rail link between Brentford and Southall. Photography: Robert Low.

Greater London House, Camden: When the Carreras Cigarette Factory was built in the 1920s, it was the largest reinforced concrete factory in Britain, if not Europe. With massive floor plates of 55,000 sq ft, and huge expanses of open space, it was a symbol of all that the modernists stood for. But its front facade was far from it. The Art Deco styling, including Egyptian columns, black cats and a cornice that gave the form of an Egyptian temple – fell victim to modernist dogma in the 1960s and was stripped back and covered up. A massive restoration job in 1999 saw the facade restored to its former glory by Finch Forman. Its loft-style interiors were turned into office spaces by Munkenbeck + Marshall, now inhabited by media and tech companies.

Greater London House, Camden: Black cats overlook passers-by. Photography: Tony Hisgett.

Hoover Building, Perivale: Another Art Deco icon with Egyptian detailing, the 1930s Hoover building in Perivale was a seminal project for Wallis, Gilbert & Partners, big players on the British industrial architecture scene. Its main building is a low-lying, two-storey structure divided into 15 bays by Egyptian pillars. Photography: Ewan Munro

Hoover Building, Perivale: The front facade has a distinctive, fluted frieze and an elevated central pediment. Production halted at the site in the early 1980s, and it was purchased in 1989 by supermarket giant Tesco, who struck a deal with English Heritage to retain the most significant structures and demolish subsidiary parts. Photography: Robin Webster.

Enterprise House, Hayes: Vinyl records are still being pressed in the six-storey Gramophone Company building, later known as the EMI building and now Enterprise House. It’s the first known work of engineer-turned-architect Sir Owen Williams, whose other pre-war feats include London’s Dorchester Hotel and Nottingham’s Boots factory. Williams pioneered the use of the Truscon system of reinforced concrete in the UK at Enterprise House, which was patented in Detroit by Julius Kahn. The 1912 building’s frame is clearly expressed as a composition – an early example of the modernist battle-cry ‘form follows function’. Today, the building houses The Vinyl Factory’s pressing plant and offices for the creative industries operated by Workspace, while planning permission has been granted to turn the remainder into light-filled flats. Enterprise House is part of a cluster of former EMI buildings in Hayes – including buildings by Wallis, Gilbert & Partners – currently being revived. They will soon connected to London by the Crossrail artery.

Enterprise House, Hayes: The Vinyl Factory’s pressing plant on the ground floor of the building. Photography: Marco Walker.

Enterprise House, Hayes: Original EMI factory equipment is still in action. Photography: Marco Walker.

Wapping Hydraulic Power Station: Built in the 1890s to power London machinery and lifts, the Grade II-listed Wapping station shut in 1977 and lay derelict until rescued by Jules Wright and Shed 54 in 2000, who turned it from ‘a den of itinerant heroin users’ into The Wapping Project, an arts centre and restaurant. Photography: Ewan Munro.

Wapping Hydraulic Power Station: It closed again in 2013 after ruckus about noise levels with neighbours and was bought by Nick Capstick-Dale, the developer behind the transformation of nearby Metropolitan Wharf – a Victorian tea warehouse – into flats and offices. Photography: Thomas Zanon-Larcher, courtesy of The Wapping Project.

Wapping Hydraulic Power Station: Speaking to Property Week last year, Capstick-Dale loosely floated two options: ‘It will be a farmers’ market-cum-restaurant-cum-cookery school,’ he said, adding, ‘the other alternative is that it would be a boutique hotel.’ No planning applications for the power station have yet been submitted. Photography: Thomas Zanon-Larcher, courtesy of The Wapping Project.

Millenium Mills, West Silvertown: East London’s Royal Docks were once the centre of the city’s flour milling industry, lorded over by the hulking Millenium Mills. Built in 1905, and rebuilt in 1933 after a fire, the concrete-framed Art Deco edifice holds half a million sq ft of space. It closed in the 1980s and has since been a location for films, music videos and TV shows, and more illicitly as a place for ‘urban exploring’. Boosted by £12m of government funding, renovation work has now begun on the building – albeit hampered by a fire in February – led by the Silvertown Partnership as part of a £3.5b transformation of the Royal Docks. The site is being developed in phases, the first of which includes the building itself, scheduled for completion in 2017. It will be transformed into a hub for start-up businesses, flanked by new homes in surrounding land. Photography: Tom Page

Lots Road Power Station, Chelsea: Plans are afoot to resurrect the Lots Road Power Station, built in 1904, into a mixed use development. Dubbed ‘the nerve centre of London’s underground’, it provided power for most of the network until 1990 and was the longest-serving power station in the world when finally decommissioned in 2002. Two of its original four chimneys have survived and, at 275 ft, were the tallest in Europe when built. Now part of a £1b master plan devised by architect Sir Terry Farrell for developers Hutchison Whampoa, the station will be converted into residences, flanked by two new towers, slated for completion in 2018. Interest can be registered at Chelsea-waterfront.co.uk.