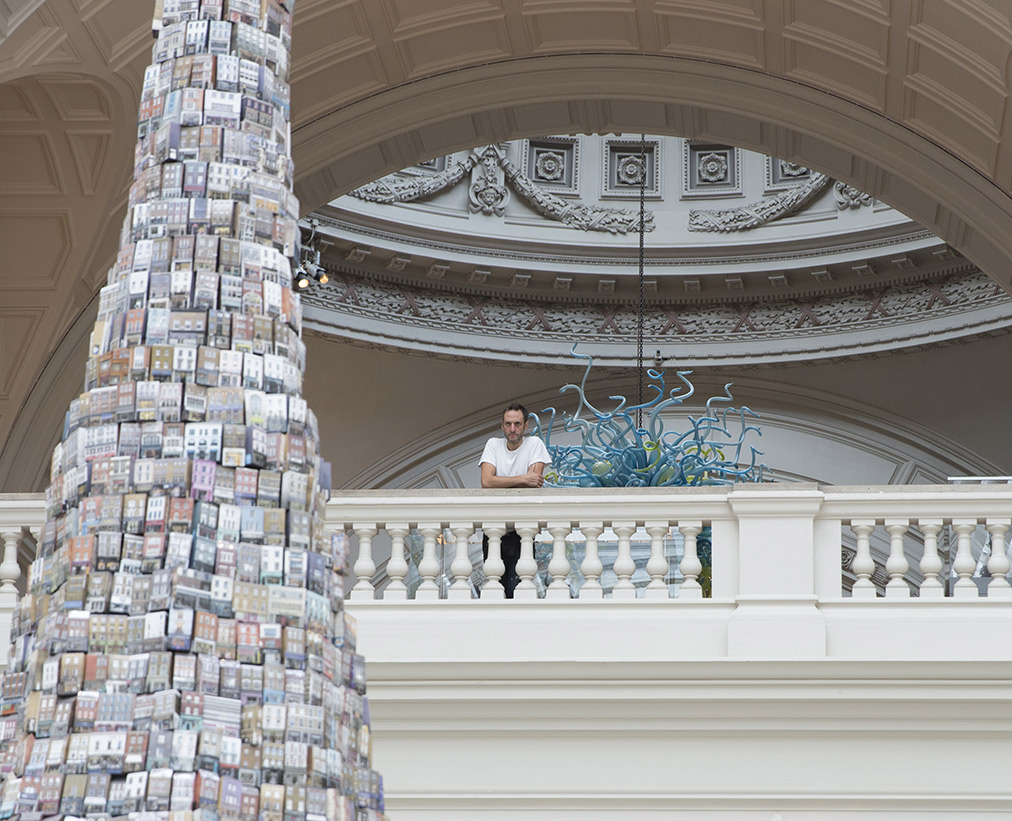

Installation view of The Tower of Babel inside The Victoria and Albert Museum’s Medieval and Renaissance Galleries. Image: Courtesy of the artist and the Victoria and Albert Museum

Image: Courtesy of the artist and the Victoria and Albert Museum

Image: Courtesy of the artist and the Victoria and Albert Museum

Image: Courtesy of the artist and the Victoria and Albert Museum

Image: Courtesy of the artist and the Victoria and Albert Museum

Image: Courtesy of the artist and the Victoria and Albert Museum

Surrounded by 16th century statues and rising high in the atrium of London’s V&A, Barnaby Barford’s Tower of Babel has just opened to the public but it is already becoming a relic of a city that is changing fast.

Barford spent two years bicycling around the capital photographing its storefronts. Ranging from derelict shops to gleaming luxury boutiques, his images were transferred on to 3,000 porcelain miniatures, before being stacked up as a 6.5-metre sculpture.

At its base are the shuttered stores, followed by brothels, nail salons and corner shops, while the likes of Harrods, Sotheby’s and Hauser & Wirth crown its peak.

Riffing off its biblical namesake – where the people of Babel tried to build a tower to heaven – Barford’s ceramic sculpture stands as a monument to the British love of shopping and our attempt to find fulfilment through consumerism. It’s also no coincidence that it’s the first project to be both exhibited and offered for sale via the V&A’s shop.

‘I’m not really an activist for the high street,’ Barford says. ‘I see myself more as an observer, watching what happens.’

One of the things Barford is observing, now that the tower has been unveiled, is people’s reactions to it. ‘You look for where you live and shops that you know and the brands you aspire to,’ he says. But, from the bookmakers to the chicken shop, ‘they’re all beautiful – they’re people’s businesses, they’re people’s homes, [they represent] their hopes and dreams. They all play such an integral role to the city’.

We find out more about his vision of London.

Art galleries like the Gagosian, Sadie Coles, Pace and Sotheby’s auction house are at the top: is this a comment on how inaccessible art – particularly within in gallery spaces – can feel to some?

Anyone can go into the art galleries. We might go in and look but we’re not going to buy anything. They are shops, aren’t they? I’ve reduced everything to a shop. Christie’s is a shop; the Gagosian is a shop. They don’t market themselves that way but they sell stuff the same as shops down at the bottom. But the reason they are at the top of the tower is because everyone uses art to sell their stuff.

How much have London’s high streets changed since you began the project?

Loads. That’s one of the things you realise – how ephemeral they are and how quickly things do change. Some of the shops local to me have now closed and have become something different.

London is changing fast, isn’t it? But then it always has changed; it’s always moving. I’ve just captured it as it is now. I think this will become more important in 10, 20, or even 50 years’ time.

Was it important that the china shops were manufactured at Stoke potteries?

It’s very important. It felt right that they needed to be made in the UK. It’s such a beautiful material – bone china. They’re just exquisitely made.

The Tower of Babel will be on display in the Victoria and Albert Museum’s Medieval & Renaissance Galleries until 1 November 2015.