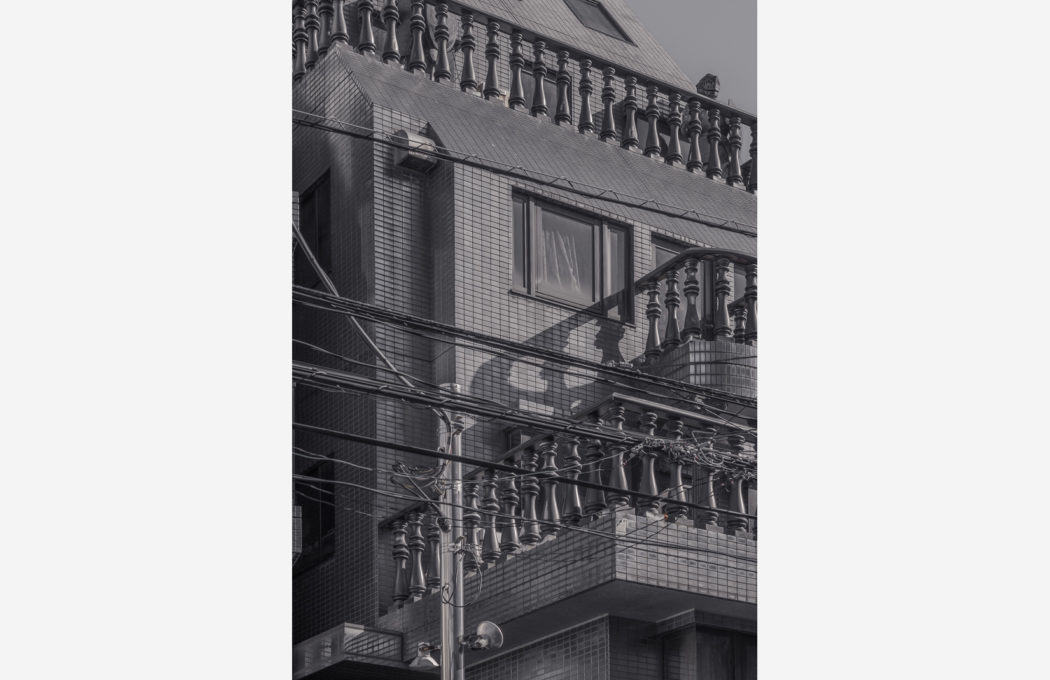

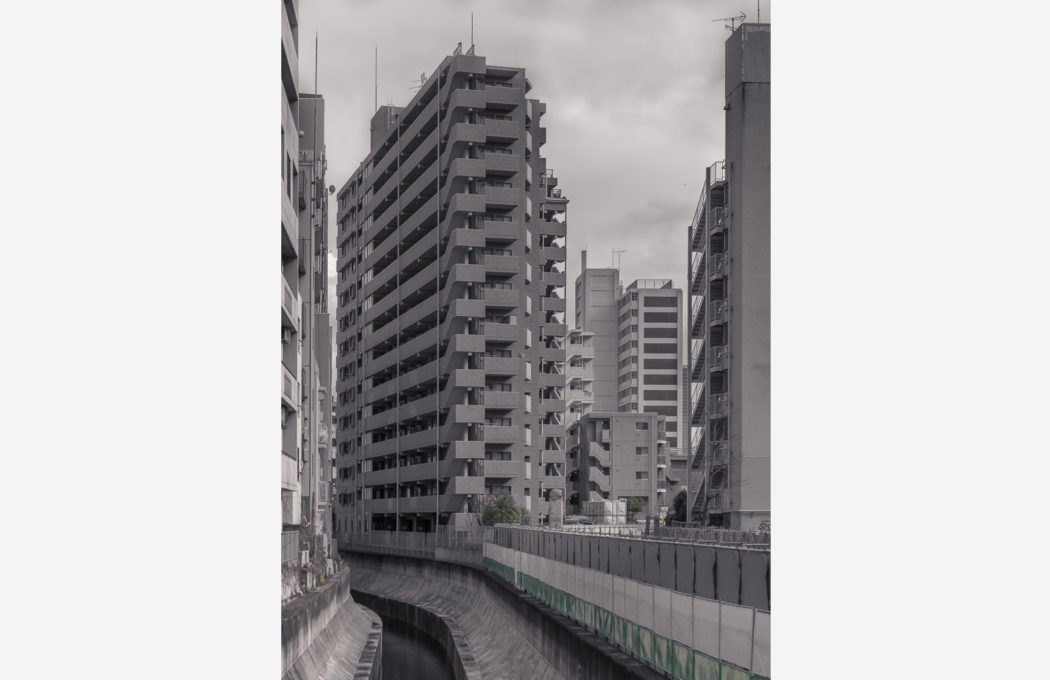

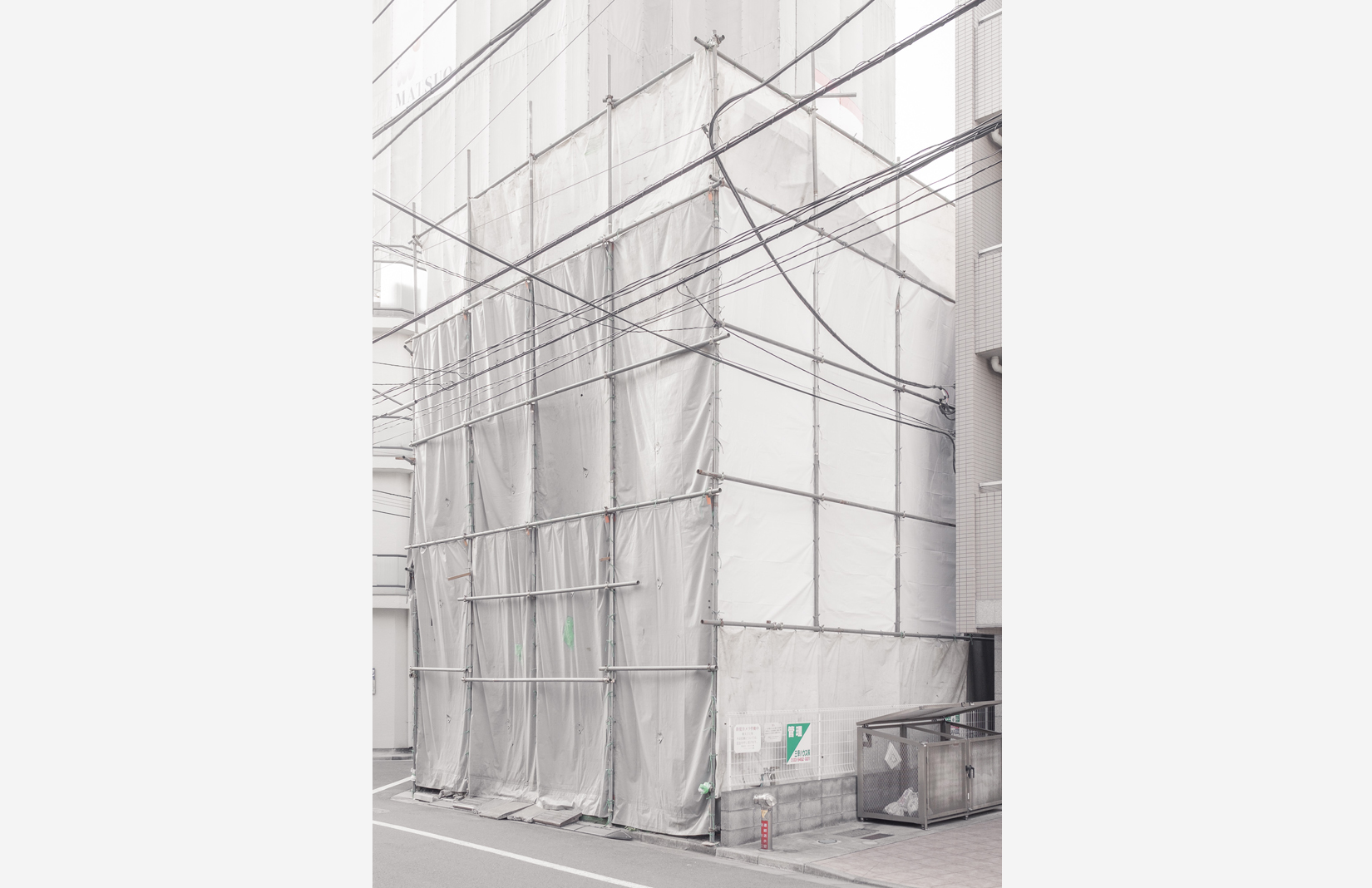

Czech photographer Jan Vranovský has created a moody portrait of Japan in his series, Parallel World.

After moving there to study a masters in architecture at the University of Tokyo, Vranovský began shooting residential prefab architecture as a way of getting to know his adopted city.

‘At first it helped me settle in and absorb local urban and social paradigms. But as time passed, my initial awe (which was very general) transformed into a specific interest in aspects of Tokyo and Japanese cities,’ he says.

These aspects became the ‘between spaces’ in the city’s urban core such as building sites and parking lots.

Photography: Jan Vranovský

Photography: Jan Vranovský

Photography: Jan Vranovský

Photography: Jan Vranovský

Photography: Jan Vranovský

Photography: Jan Vranovský

Photography: Jan Vranovský

Photography: Jan Vranovský

Photography: Jan Vranovský

Photography: Jan Vranovský

Photography: Jan Vranovský

Photography: Jan Vranovský

Photography: Jan Vranovský

Photography: Jan Vranovský

Photography: Jan Vranovský

Photography: Jan Vranovský

Photography: Jan Vranovský

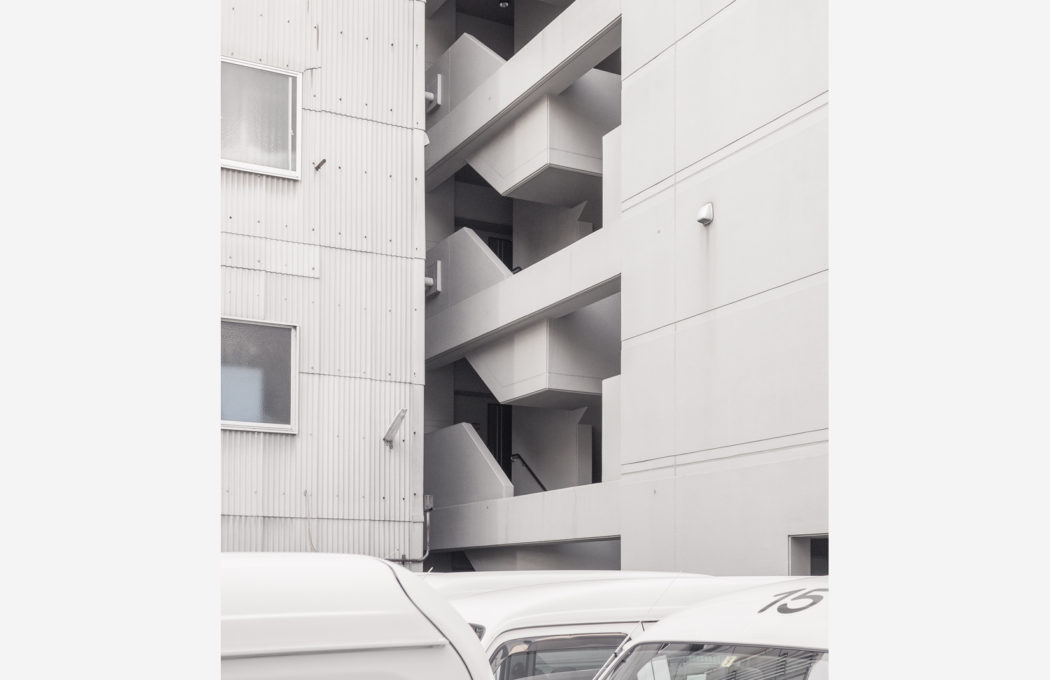

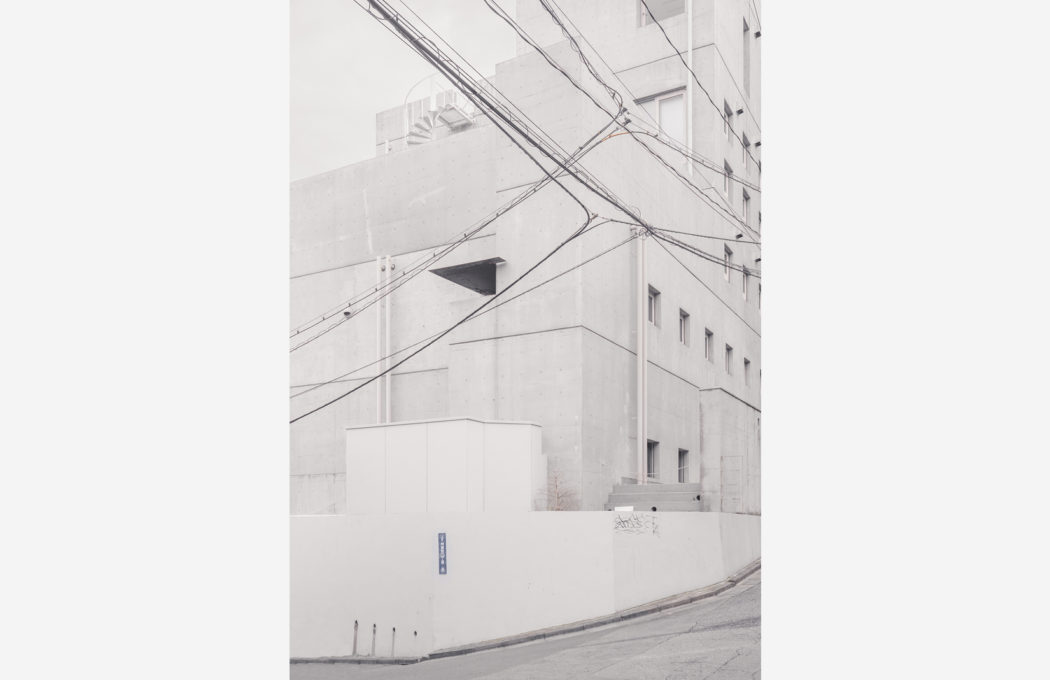

Parallel World captures the city in a moment of pause – between destruction and reconstruction – wrapped in tarpaulin and scaffolding.

‘I don’t think I’m consciously searching for a contrast between black and white, clean and messy,’ Vranovský explains. Instead, ‘I’m generally aiming for homogenous, almost computer render–like sensation in my photos.’

Look deeper and his images take on nuanced shades of pinks and blues that turn contrast into complexity. ‘[Parallel World] is really about gradients and subtle tones… nothing is black and white in Japan.’

He adds: ‘Architect Yoshinobu Ashihara describes Tokyo as an “amoeba city”: always prepared to sacrifice any of its parts so the whole can survive, always adapting to changing situations.’

In a city where the average lifespan of a building is around 30 years, these spaces suggest both the vulnerability and possibility of the city, embodied partly by the dark and light shades of Vranovský’s images.

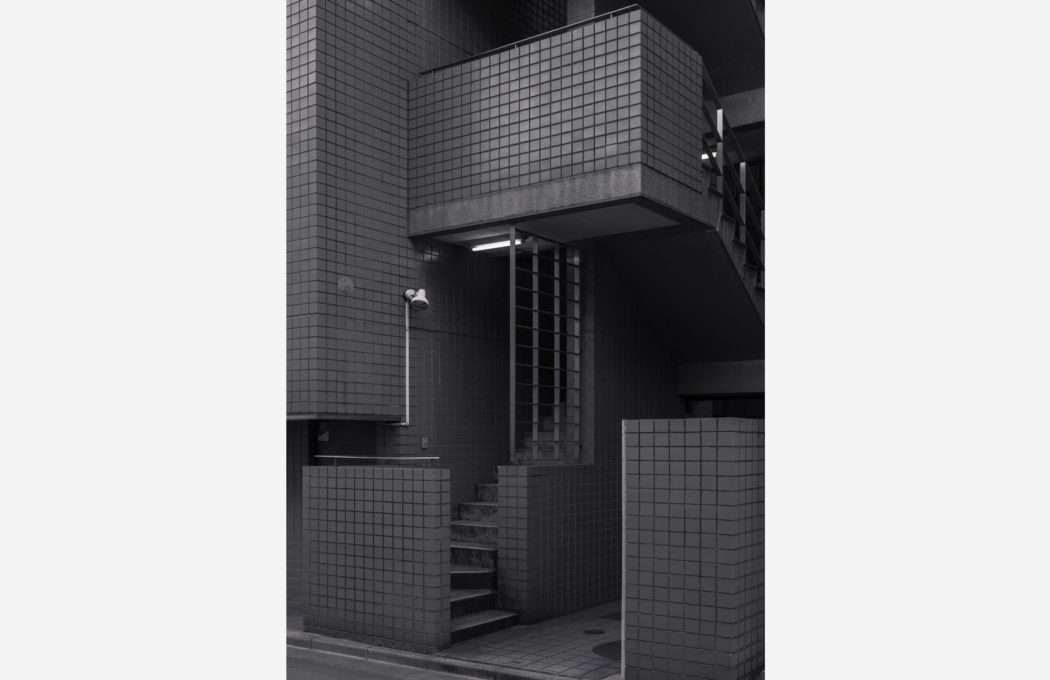

While skirting the edges of construction sites, Vranovský also developed a fascination with the hidden side of residential Japanese architecture – the backs and undersides of dwellings.

‘The front facades of houses often resemble masks. Seeing them feels like watching actors in a Greek drama, where characters and roles are formalised almost to a point of being mere symbols.’

Parallel World pays homage to architecture without architects. ‘My main focus is a “technology-age vernacular”. The vast majority of buildings in Japan are designed by licensed engineers using easy to get materials like prefabricated concrete panels, prefab tile facade systems and staircases, etc.’ Form is governed more by building regs and zoning laws than aesthetics. ‘Even attempts to make things pretty on the surface are ritualised and technocratic.’

Read next: Inside the concrete atelier of Japanese architect Tadao Ando