Ralph Schulz, ‘02.11.2010 Bornstraße’, 2010. Courtesy Ralph Schulz ©

Installation view of Andreas Schulze’s ‘Fog in the living room’ at Kunstmuseum St. Gallen in 2015 © Andreas Schulze / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2016 Photography: Stefan Rohner / Kunstmuseum St. Gallen

Matthias Weischer, ‘Yellow lamp’, 2004. Collection AV © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2016

Simone Demandt, ‘Joy of living, G 2’, 2001/03. Courtesy Simone Demandt © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2016

Romain Cadilhon, ‘Untitled (Studio # 12)’, 2015 . Courtesy CONRADS, Dusseldorf © Romain Cadilhon Photography courtesy Galerie Conrads, Dusseldorf

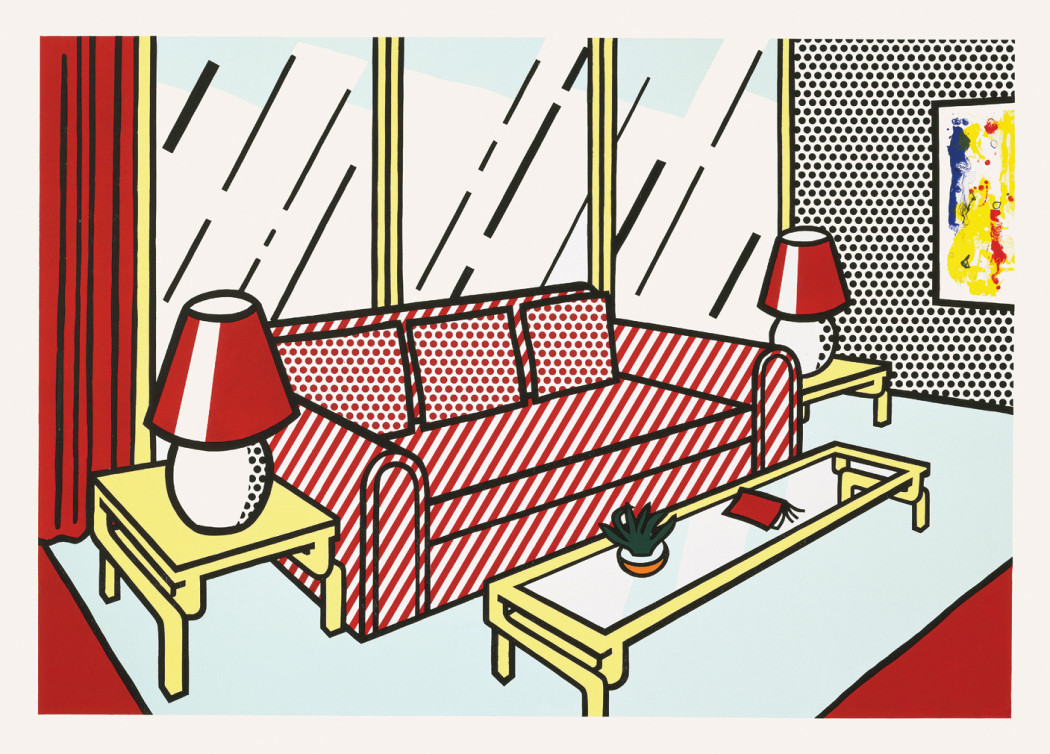

Roy Lichtenstein, ‘Red Lamps’ (from: Interior Series), 1990. Private Collection © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2016; Photo: Gemini GEL Los Angeles

Carlo Mollino, ‘Untitled’, 1968-1973. Museo Casa Mollino, Turin © Museo Casa Mollino

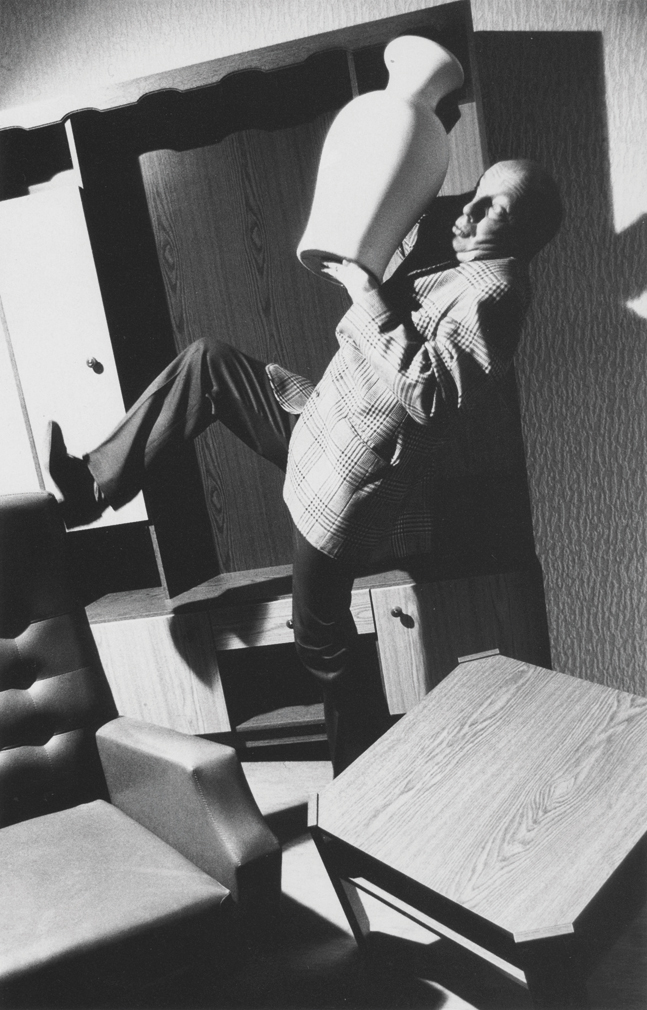

Anna and Bernhard Blume, ‘Vasenextase’, 1987. Photography from the 28-part sequence © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2016

What is our relationship to the home? Is it a sanctuary and an honest expression of the self? Or is it a stage set where we perform in public view? In Insightful Rooms: The Interior as Portrait, the Museum Morsbroich connects the work of 17 contemporary artists probing these questions against the backdrop of its own flamboyant interiors.

Morsbroich – in Leverkusen, Germany – has been a contemporary art museum since the 1950s, but far from being a suite of bland white cubes, its reception rooms bristle with Rococo curlicues that betray its former life as a 19th-century maison de plaisance.

‘Schloss Morsbroich, in which the museum is housed, forms a very special portrait of the former owners in itself,’ explains curator Fritz Emslander. ‘The hall of mirrors, the hunting room and the women’s withdrawing room tell the story of a rich family of textile manufacturers with a strong desire for representation.’

This interior is addressed in a fantastical installation by Claus Richter, who reimagines the schloss’s former occupants as eccentric bird enthusiasts.

Another room-sized work – Andrea Zittel’s ‘Pattern of Habit’ (2011) – charts the artist’s Internet usage over 39 days. Zittel lives in the desert, but even in such ultimate isolation, the illusion of sanctuary is broken by the artist’s reliance on regular deliveries of packaged supplies and hours spent connected online to the outside world. ‘One’s own four walls have become permeable,’ notes Emslander.

More vernacular dwelling spaces are investigated in the photographic works of Miriam Bäckström. In the 1990s the Swedish artist created ‘portraits in absentia’ using deserted interiors including historic arrangements from the IKEA museum, and the homes of the recently deceased.

The blank cosiness of the former contrasts strongly with the unintentional candour of the latter, which memorably includes a linen cupboard door lined with pictures of busty women.

Ralph Schulz, too, brings focus to objects not intended for public view. The uncanny interiors shown in his photographs are assembled from domestic debris left out for the council’s bulky waste collections. Not so much ‘portraits in absentia’ as ‘portraits in the negative’ – visions of the rejected.

As Emslander points out, where once the concept of interior as indirect portrait was the preserve of the rich, social media now gives the public a view through the keyhole. It’s no longer just the ultra wealthy that present their homes like theatre sets on which to play out their lives in the public eye.