Designers are constantly looking forward. We look at things and wonder how they could be, how we think they should be, and we find inspiration in the excitement of the future.

Yet all too often we forget to look back, to see the great works that have come before us and the incredible people whose lives have shaped our present.

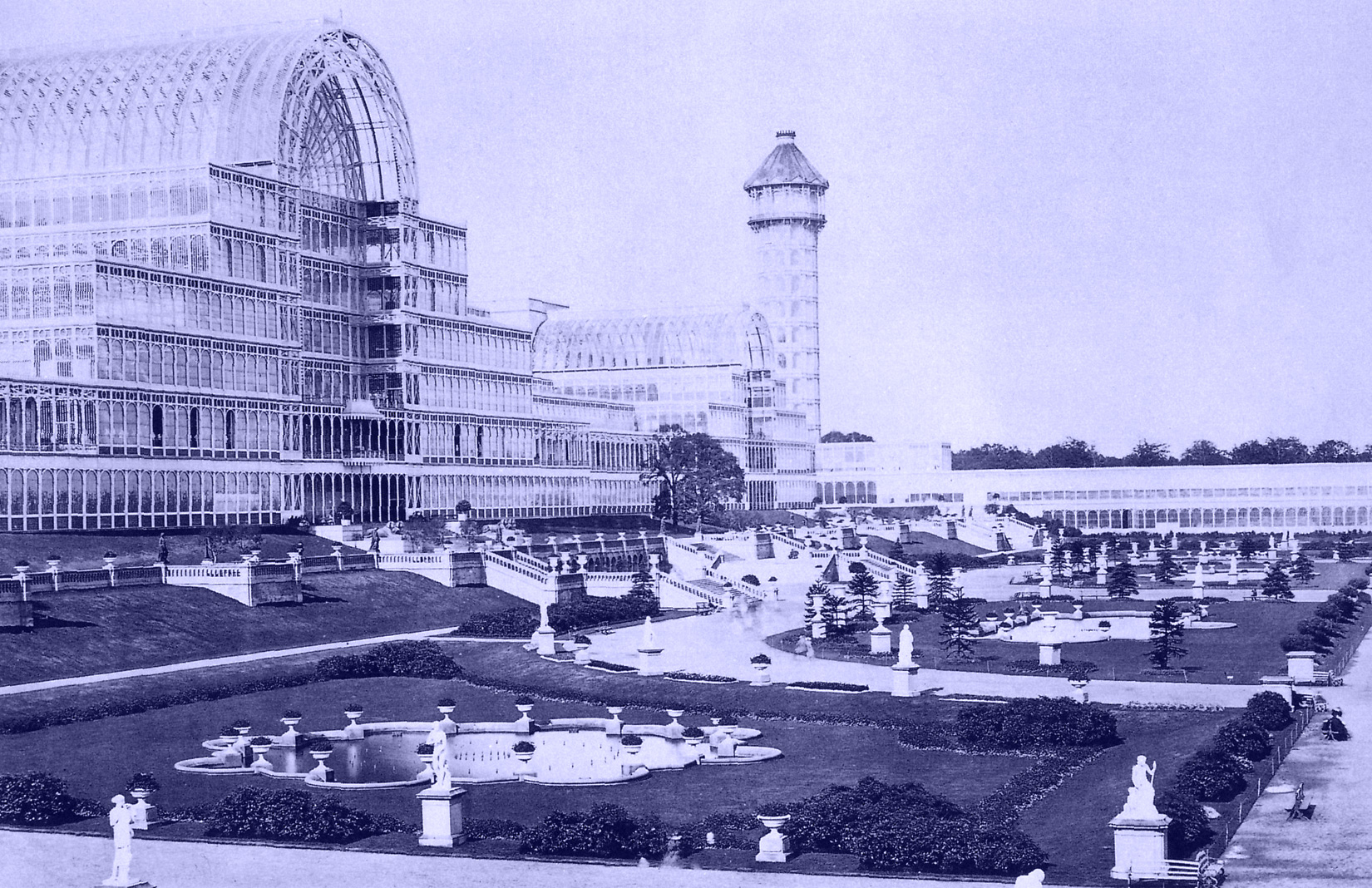

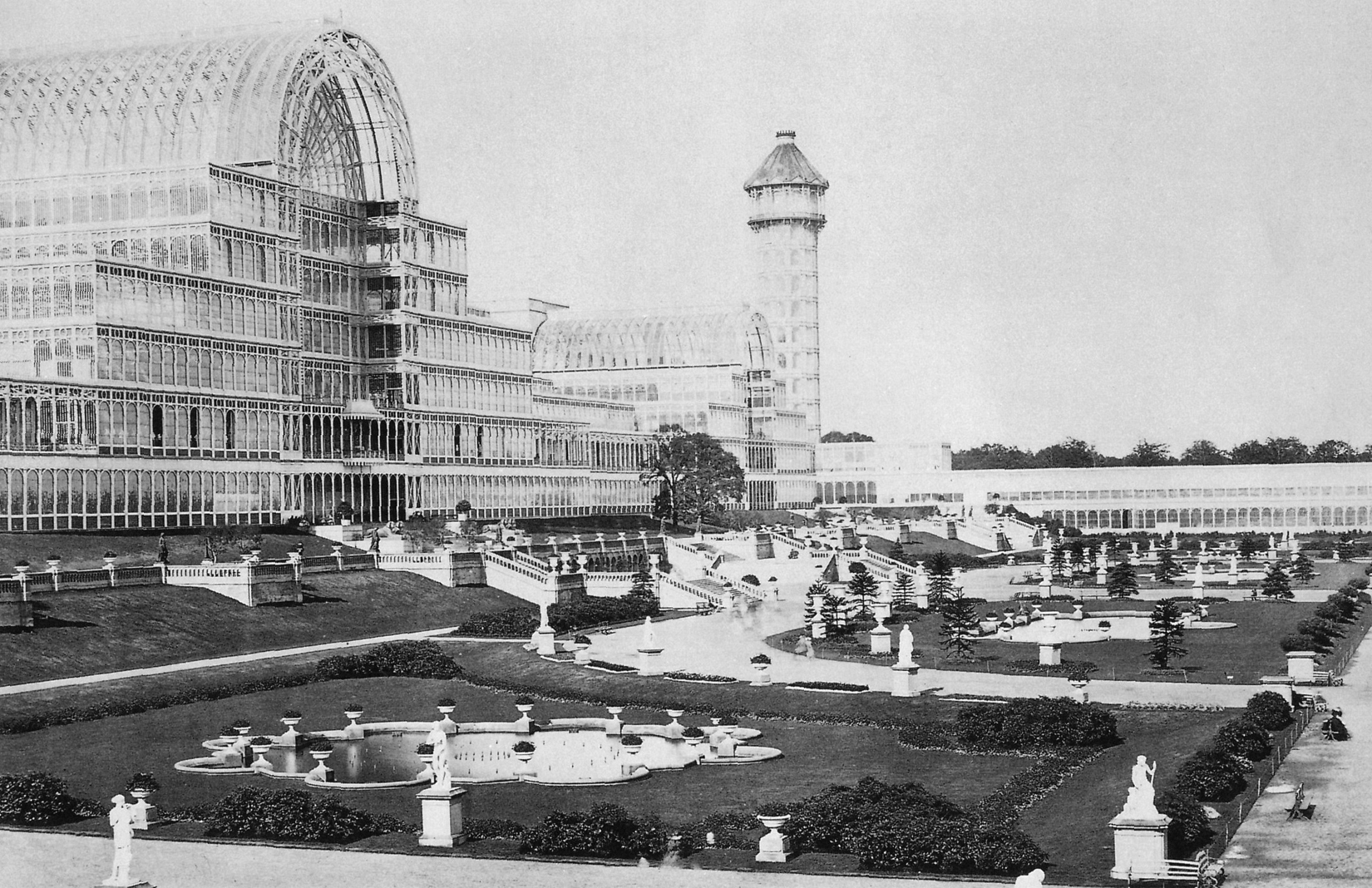

Back in the autumn of 1851, the largest building on Earth had risen from Hyde Park in just a matter of weeks. It was the gigantic hall for the ‘Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations’. It was Victorian England’s cathedral to a century’s worth of innovation in engineering and design, eclipsing every effort of architecture that had come before it.

Just ten months before, however, it looked like there might not be a Great Exhibition at all. The committee in charge of delivering the event, which boasted the epic title ‘The Royal Commission for the Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations’, was facing disaster. They had spent months spinning their wheels, stuck in indecision: 245 designs had been submitted in a competition for the design of the exhibition hall, and all were rejected as unworkable.

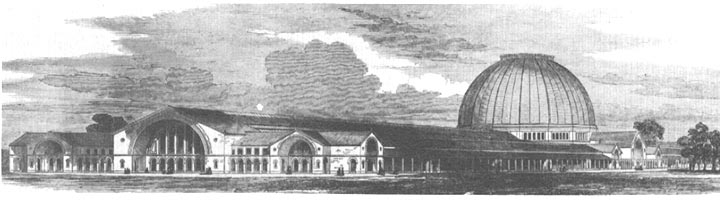

Running out of time and money, the committee did what many a desperate committee has done before. They commissioned another committee with a better name. ‘The Building Committee of the Royal Commission for the Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations’ was created and the nation’s faith placed in its chairman, the great engineer, Isambard Kingdom Brunel.

Brunel excelled at many things, but working to tight deadlines wasn’t one of them and his hastened vision for the Exhibition hall did not sit well with the public. Its focal point was a black iron dome that was as oppressing as it was massive. The dome – which looked like a meteorite that had crashed to Earth – sat atop a low and long brick warehouse-like edifice with small windows and gloomy corridors contained within. A newspaper at the time described it as having ‘all the spirit and playfulness of an abattoir’.

Into this unfolding national embarrassment entered the figure of Joseph Paxton, the head gardener at Chatsworth House.

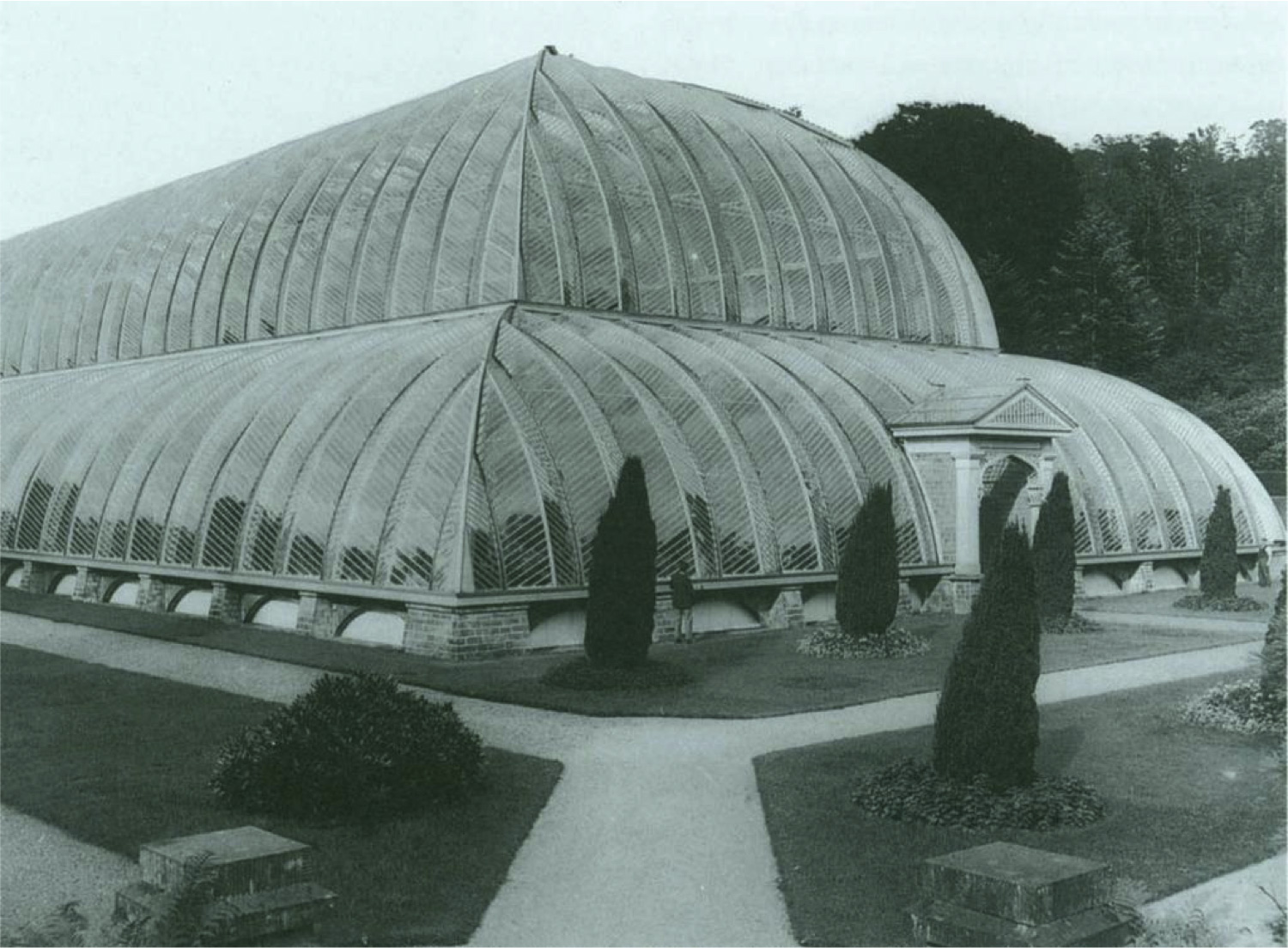

Paxton had been building glasshouses to house tropical fruits and trees from the farthest reaches of the British Empire. The biggest of these was The Great Stove, for which he used a minimal amount of brick, instead opting for iron railings from which glass was hung. Paxton developed genius methods of construction while experimenting with glasshouses, which he was sure would scale to the size needed to build the Great Exhibition hall.

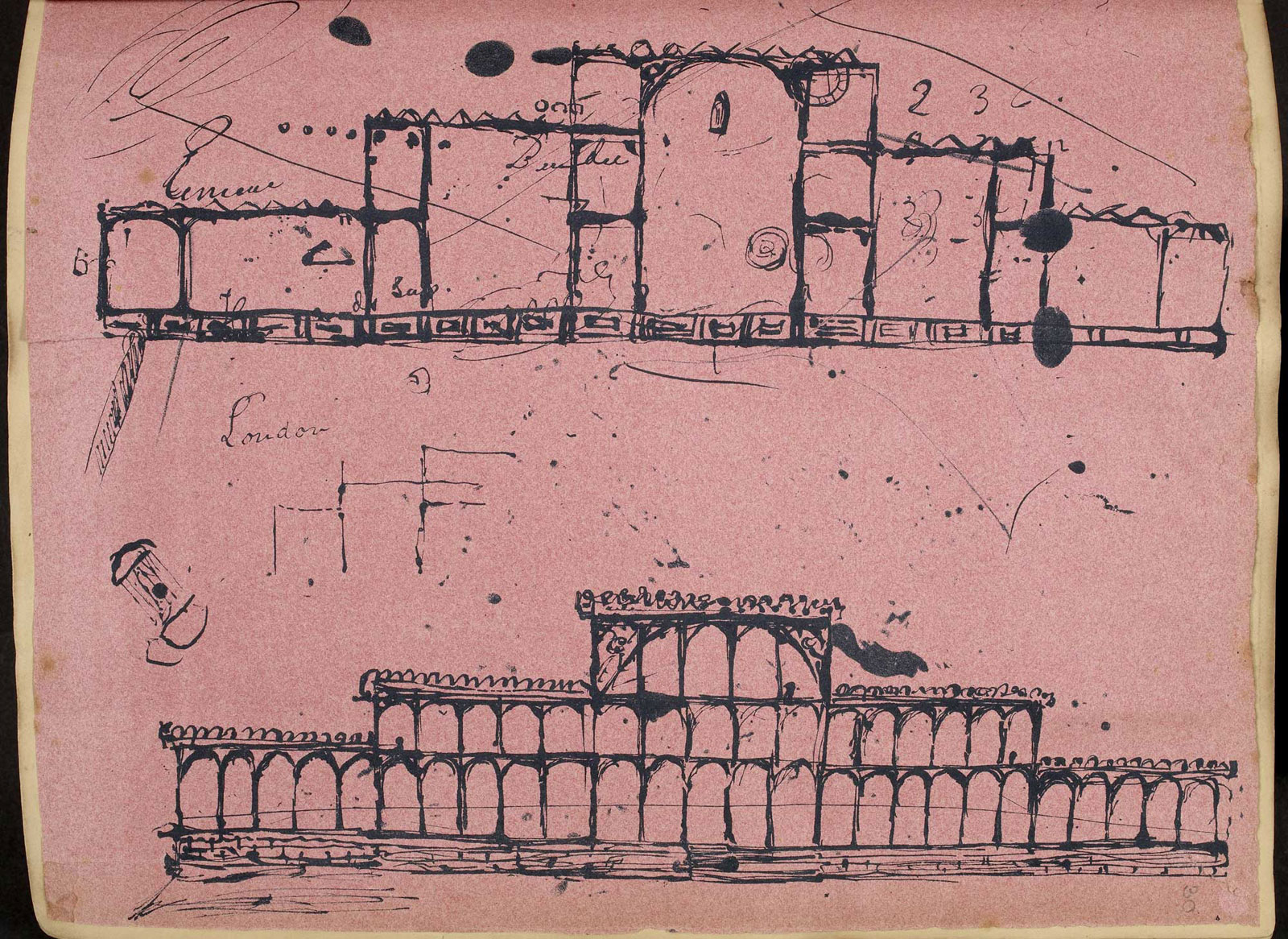

When Paxton heard about the difficulties Brunel was having with the design of the exhibition hall, he wondered whether something like his glasshouses could work. He sketched on a napkin a rough concept of how the building would be constructed – two weeks later, he had finished designs submitted to the committee.

Paxton’s design was an unlikely candidate for success. It broke many of the competition rules; first and foremost, that it was six months late for the competition. His design also incorporated the use of wood flooring, which was prohibited because of its flammability. Even more damningly, Paxton had had no formal education in architecture and had never attempted anything on this scale before.

In a twist of marketing genius, Paxton also published his designs in the Illustrated London News. The public loved them. Just a few days later, Brunel’s committee approved Paxton’s idea and work began.

It’s hard for us to imagine just how revolutionary this construction was. There were no foundations, no bricks; just huge plates of glass and a skeleton of iron. The whole thing could be prefabricated from standard parts, just like how skyscrapers are constructed today.

From start to finish, the entire project took just 35 weeks.

We’re so used to seeing glass in huge edifices today, but to a visitor to Hyde Park in 1851, the Crystal Palace would have seemed magical. Thanks to the unpopular ‘window tax’ – which would not be repealed for another five years – most London dwellings were dark and gloomy for the majority of their inhabitants. At the Crystal Palace, however, people experienced being indoors yet basked in light.

The feeling of spaciousness, of continuity with nature, must have been euphoric.

Since then, the architectural community has never looked back.

The next time then that you are struggling for inspiration, think perhaps of the gardener who, against all expectation, changed the way the world thought about construction with a simple sketch on a napkin.

Alasdair Monk is a leading inteface designer and app developer at Heroku. This story is adapted from a presentation given at at General Assembly’s Design Night Marathon on the subject, ‘Things you didn’t know about design’. Alasdair can be found tweeting @almonk