Serpentine Pavilion 2017, designed by Francis Kéré. Serpentine Gallery, London (23 June – 8 October 2017) © Kéré Architecture: Photography: © 2017 Iwan Baan

Serpentine Pavilion 2017, designed by Francis Kéré. Serpentine Gallery, London (23 June – 8 October 2017) © Kéré Architecture: Photography: © 2017 Iwan Baan

Serpentine Pavilion 2017, designed by Francis Kéré. Serpentine Gallery, London (23 June – 8 October 2017) © Kéré Architecture: Photography: © 2017 Iwan Baan

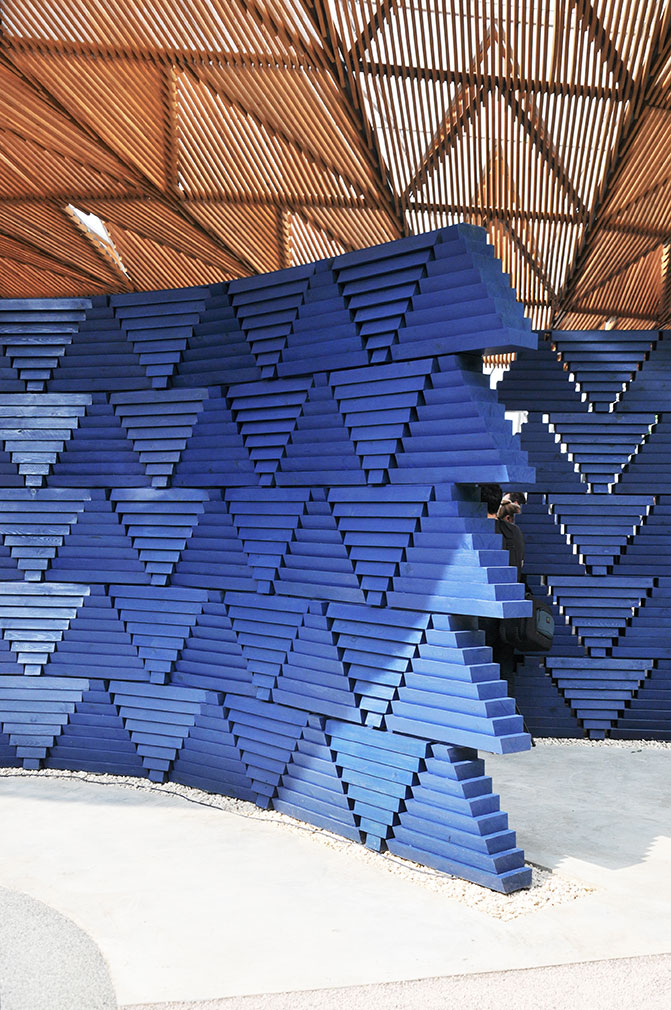

Serpentine Pavilion 2017, designed by Francis Kéré. Photography: Rosella Degori

Serpentine Pavilion 2017, designed by Francis Kéré. Photography: Rosella Degori

Serpentine Pavilion 2017, designed by Francis Kéré. Photography: Rosella Degori

Serpentine Pavilion 2017, designed by Francis Kéré. Photography: Rosella Degori

Diébédo Francis Kéré’s 2017 Serpentine Pavilion embraces Londoners’ favourite talking point – the weather – offering shade from the elements while turning rain into a spectacular central waterfall.

The architect took design cues from a tree, the traditional meeting point for life in his native Burkina Faso. Rainwater will pour off the canopy-like roof – made from timber slats covered by a transparent skin – and down into a void within the steel framework that supports the Kensington Gardens structure.

‘In time it will rain,’ said Francis Kéré’ at the Serpentine Pavilion’s preview today in the blaze of the unusually hot London sun. ‘You will be safe, protected by the structure but you will feel the effect of the waterfall, here in the middle of the pavilion. I wanted to celebrate water.’

His oval pavilion (opening to the public on 23 June) has four entrances and, beneath the canopy, there are gaps that enable air to circulate freely. Dappled sunlight will also filter through the roof.

‘It is breathing; the walls are open,’ said Kéré. ‘I wanted to create an open space where people can gather in many different ways.’

On sunny days they can shelter under the canopy or bathe in the sun in the central oculus. Kéré’s pavilion comes wrapped in stacked timber walls that look like woven fabric in a brilliant shade of indigo.

‘In my culture, blue is an important colour,’ Kéré explained. It’s the colour of celebration in Burkina Faso and what young men wear on a date, according to the architect. ‘You dress indigo blue, so you’re shining when you approach the house of your dream… I wanted to present myself, my architecture in blue. You wear your best clothes.’

As with tradition for the annual Serpentine Pavilion commission – inaugurated by Zaha Hadid’s triangulated roof design in 2000 – this is Kéré’s first built structure in England. The architect, who divides his time between Berlin and the village of Gando in Burkina Faso, has built a reputation for socially driven projects. He was the only child in Gando to attend school, so his first project as an architect was to build a primary school there, funded by money he raised himself. It won him early acclaim and his projects now span from Switzerland to China.

Kéré’s flair for narrative and socially engaged, ecological architecture is what attracted the Serpentine Galleries.

‘We were definitely inspired by his passion for storytelling and the desire to convene,’ said new CEO Yana Peel, who picked the architect with artistic director Hans Ulrich Obrist and a panel of advisors, including David Adjaye and Richard Rogers.

Kéré’s design is the 17th Serpentine Pavilion and follows BIG’s ‘unzipped wall’ structure last year. BIG’s design was augmented by four summer houses as part of a bumper summer programme to mark the departure of co-director Julia Peyton-Jones, who founded the annual series.

The current pavilion will remain in situ until 8 October.

Read next: Why pavilions are the new collector’s items