As the nature of office-based work has changed in recent years, so have offices themselves. Mobile technology allows employees to be less desk-bound, and the working day has extended as staff are expected to be available beyond conventional office hours and across time zones.

Workplace designers have responded by creating different environments in one office, from casual meeting areas to quiet places and brain-storming corners.

But while these so-called ‘activity-based workspaces’ are intended to boost productivity, one element of staff well-being has remained largely neglected.

‘Clients that we’re dealing with aren’t really too concerned about sleep at the moment,’ admits Felicity Roocke of architecture practice Hassell.

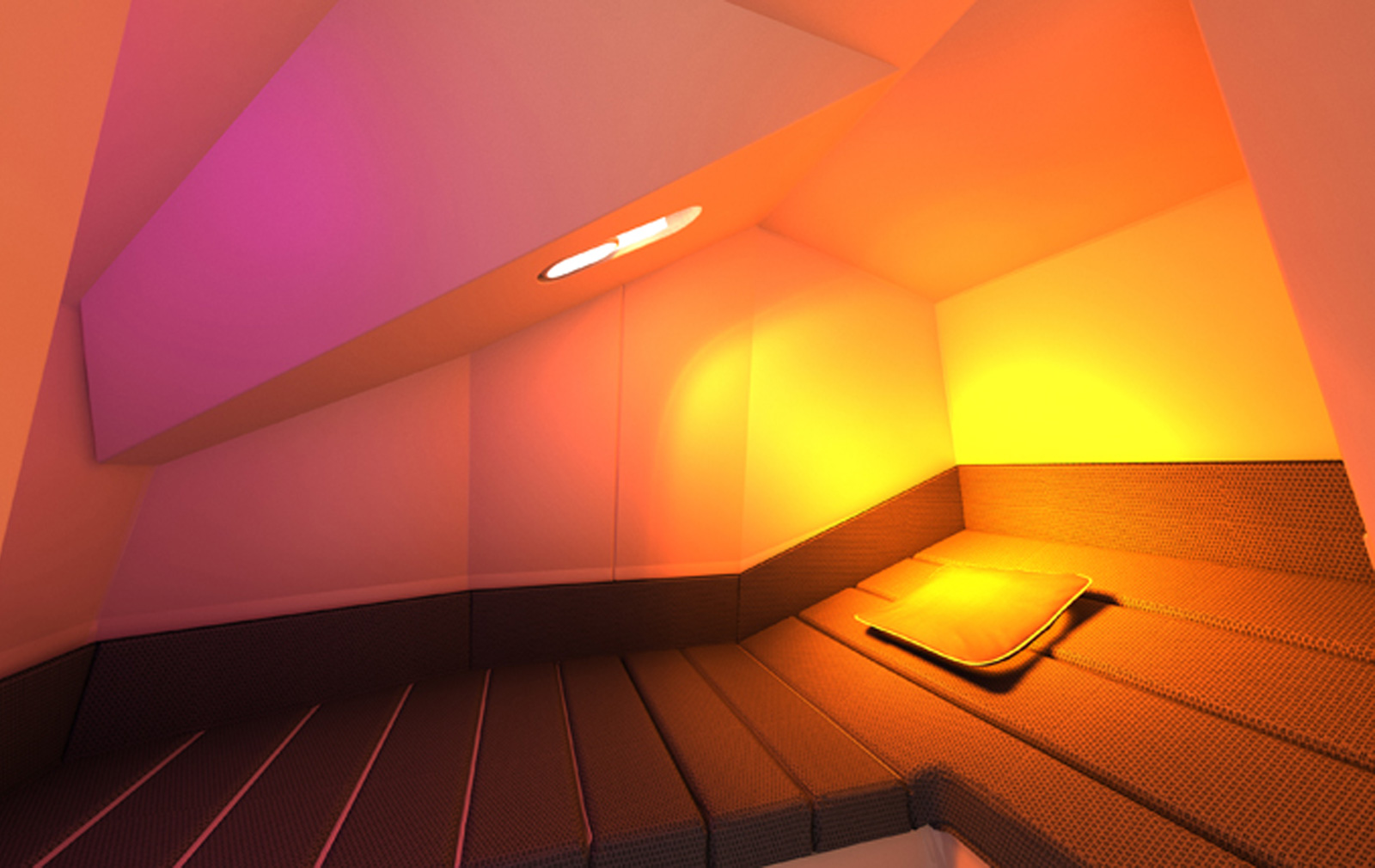

She spoke about these issues at last month’s panel discussion Hypnos: ‘Sleeping In-Between Home and Work’, hosted by Sto Werkstatt. The event was inspired by Sto Werkstatt’s installation The Sleeperie, designed by Hassell and Draisci Studio.

Twenty-first century working patterns mean that staff are often tired, particularly when working long hours and socialising with clients in the evening. ‘Colleagues were sleeping in toilets, using toilet rolls as pillows. Or they were sleeping at their desks,’ says Jon Gray, a former employee of UBS and Merrill Lynch.

Few employers encourage their workers to catch up on sleep during the day. There’s a taboo around the subject, the assumption being that sleeping is synonymous with slacking.

What’s more, Gray admits that some potential customers are uncomfortable with setting aside rest space, the implication being that staff are expected to stay even later. But he insists that, ‘We’re not advocating staying at work for longer, we’re saying stay at work for the same amount of time, but take 15 minutes out of the day.’

Gray is one of a handful of pioneers trying to change that mindset, by introducing areas for rest into frenetic workplaces. He co-founded Podtime, which manufactures ‘sleep capsules’; likewise furniture company Haworth has a stand-alone box room called CalmSpace by Marie-Virginie Berbet, a designer with a background in neuropharmacology; and the company Sleepbox sells lozenge-shaped pods for the same purpose.

‘We are designed to have two sleeps a day,’ says sleep neuroscientist Professor Jim Horne, who established the Loughborough Sleep Research Centre. All three businesses trumpet the scientific benefits of a 15-20-minute power nap.

It is relatively early days for this niche sector, and these sleep pods and capsules are largely installed in small numbers. Facebook has five of Gray’s Podtime pods, for example, and there are two CalmSpace nap pods at UBS in Switzerland, while the international business solution company Coins has put four Sleepboxes in its HQ in Slough.

Roocke at Hassell predicts that workplace clients will increasingly appreciate the benefits of a designated sleep or rest zone. ‘A lot of our clients are all about how they can get the most productivity out of staff, and we know that sleep is intrinsically linked with productivity.’

So we could be on the cusp of a sleep revolution. And perhaps in the future people will talk of ‘designing out tiredness’ from the workplace, in the same way that the Design Council and others promote ‘designing out crime’ with safer environments, or some urban planners hope to ‘design out obesity’ by making cities more pedestrian – and cycle – friendly.

Horne cautions against mistreating the concept, however: ‘Napping is something that’s encouraged within reason. If you have a workplace where people are not getting enough sleep at night, and are therefore coming to work in a sleepy state, and using the workplace to make up their sleep, that’s not a good way of doing things.’

So it’s back to perfecting the work-life balance.