Photography: Tom Harris © Hedrich Blessing. Courtesy of Rebuild Foundation

Photography: Tom Harris © Hedrich Blessing. Courtesy of Rebuild Foundation

Photography: Tom Harris © Hedrich Blessing. Courtesy of Rebuild Foundation

Photography: Steve Hall © Hedrich Blessing. Courtesy of Rebuild Foundation

Photography: Ian Spula

Photography: Steve Hall © Hedrich Blessing. Courtesy of Rebuild Foundation

Photography: Ian Spula

Photography: Steve Hall © Hedrich Blessing. Courtesy of Rebuild Foundation

Photography: Tom Harris © Hedrich Blessing. Courtesy of Rebuild Foundation

Photography: Tom Harris © Hedrich Blessing. Courtesy of Rebuild Foundation

Two weeks before Chicago’s Stony Island Arts Bank is to open to the public, artist and urban planner Theaster Gates cracked the doors for a preview of the bank-turned-community arts centre.

A 1923 neoclassical structure, with fluted columns and terra cotta, the bank anchored a once-vibrant South Side neighbourhood – an area that has lost half its population since 1960.

‘The bank is right on this eight-lane highway of a street, years ago the heart of a thriving black community,’ says Ken Stewart, CEO of Rebuild Foundation, the not-for-profit created by Gates in 2010 to fund and administer his urban reclamations – now totalling four. ‘It’s a hulking vestige of this lost vibrancy, and so had special significance for us. Other structures on the block are gone.’

Gates bought the 17,000-square-foot bank from the City of Chicago for $1 in 2012, on the condition he fix it up. Ever resourceful, he chiselled a currency right from the building’s marble cladding to fund its adaptive reuse. One hundred of these ‘bank bonds’, inscribed with the words ‘In ART we trust’, were sold at Art Basel for $5,000 a pop. And on Saturday, Rebuild’s benefit dinner raised more than $1.1 million for the cause.

Gates is demonstrating another archetype of what an artist-run space looks like.

‘One question I’m always asking myself is: “Who has the right to amazing culture?” I would say that right is often relegated to the wealthy and elite. It’s rare that cultural producers, those who make jazz and make films and innovate dance and music and theater on the streets, would ever have the formal platforms that allow for the full celebration and maturation of their talent…. Seeing Jay-Z in his big Brooklyn arena, I’ve come to believe all one has to do is build the space you want to rock in.’

With an eye for texture and style Gates allowed the restoration to show the marks of 30 years of vacancy and neglect. The building has the feel of an archeological dig in progress, virgin territory open to discoveries of its users.

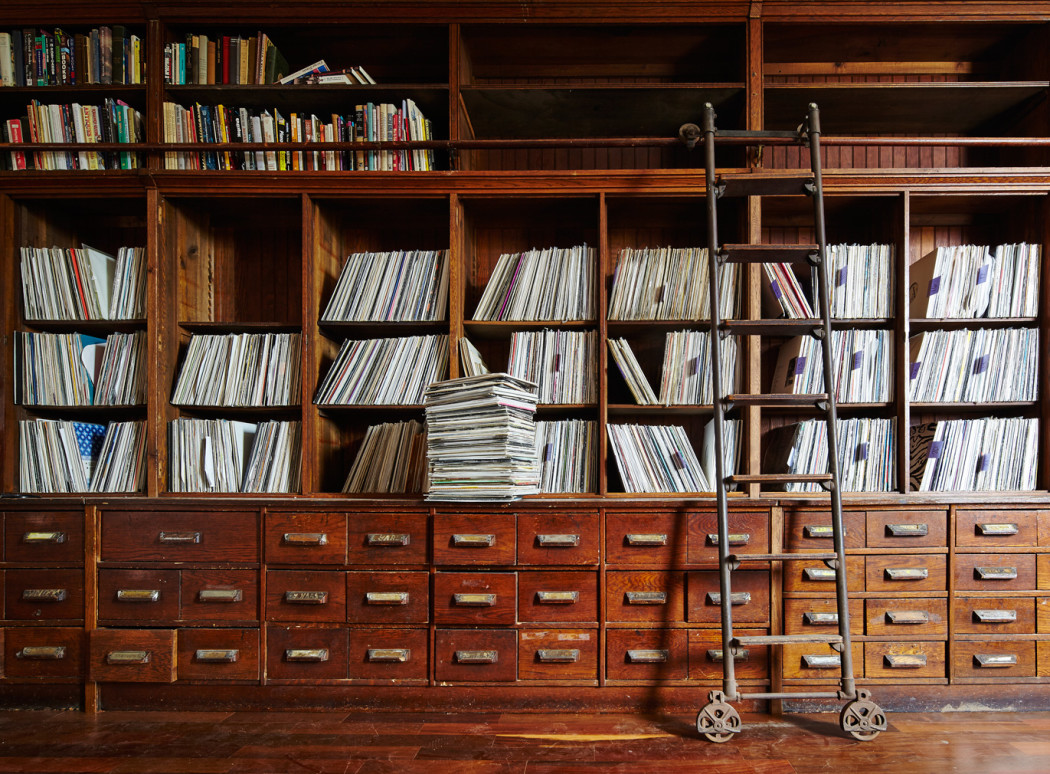

Most of the debris is gone and the structure is safe to inhabit again, but note the water damage, the cracked paint and plaster, and the disintegrating safe deposit boxes in the unimproved basement vault. Exposed lighting fixtures, recycled shelving and card filing units, and picnic tables built from the thick redwood of rooftop water tanks fit the aesthetic and Gates’ personal mandate to reenergise systems and materials that have fallen out of circulation.

‘The building has the feel of an archeological dig in progress, virgin territory open to discoveries of its users’

The reference material on deposit is outmoded media in the digital age. Artists and curious locals have a chance to breathe new life into the LP collection of the late house music legend Frankie Knuckles, art slides from The Art Institute of Chicago and University of Chicago, and the book and periodical library of John H. Johnson, founder of Ebony and Jet magazines.

It’s a model that’s transferable, and finds company in Houston’s Project Row Houses and LA’s Art + Practice, but Gates doesn’t love the notion of ‘scalability’: ‘I don’t really like the term because it feels like the goal is to do it again and again like Pizza Hut, so that the more Pizza Huts you have the more money you can make. If the question is “Can ideologies be shared?” I think that can happen.

‘The beauty of having all our collections and programming in one place is that the public will have a very simple threshold to cross.’

The Arts Bank will open 3 October, coinciding with the inaugural Chicago Architecture Biennial, but two guest artists have already set up shop. Portuguese sculptor Carlos Bunga fitted the grand atrium with supports made of cardboard and packing tape, matching the look of corrupted plaster. And Mexican architect Frida Escobedo is building a courtyard.

Galleries are front-and-centre and at the margins. Most importantly, there’s not a white box in sight.