Artist Joan Miró’s Mallorcan studio has popped up in London’s Mayfair, complete with everything from furniture to paint pots.

The Catalonian’s atelier is the latest in a collection of recreated artists’ studios. Just last year, a replica of sculptor Henry Moore’s studio was installed in London’s Gagosian, while a version of painter Frida Kahlo’s Blue House appeared in a New York park.

No longer is it enough to display an artist’s work in a white box, it seems. Galleries have had to up the ante and offer a more immersive experience.

‘The reconstruction of Miró’s everyday processes speaks to visitors much more than suspending five works against white walls,’ says Joan Punyet Miró, the artist’s grandson. He helped create the studio replica at Mayoral gallery on London’s Duke Street, bringing over chairs, desks and a collection of objects from which the artist would draw inspiration.

‘We have to be able to reconstruct emotions, sensations, feelings,’ Punyet adds. ‘That way you can really look into Miró’s mind, his labyrinth of thought and his process of creation.’

More importantly, for Punyet, to experience the studio space is to appreciate the artist’s work. ‘Miró would never have been able to create his masterpieces if he did not have this studio in Mallorca.’

Here, we take a tour of Miró’s atelier at Mayoral gallery, as well as seven other recreated artists’ studios.

Miró’s studio recreated in London

‘My dream, once I am able to settle down somewhere, is to have a very large studio,’ Joan Miró wrote in 1938. It wasn’t until almost 20 years later that the Surrealist artist would realise that ambition, when he founded his atelier in Mallorca. Miró enlisted friend and fellow Catalan, the architect Josep Lluís Sert, to design the space, where the artist would go on to work until his death in 1983. An exhibition of his recreated studio – complete with original paintings, furniture and artefacts – runs from 21 January to 12 February at Mayoral’s London gallery on Duke Street St James’s.

Frida Kahlo’s Blue House recreated in New York

New York Botanical Garden transformed its Enid A Haupt Conservatory into the family home of Mexican painter Frida Kahlo (1907-1954) for its spring 2015 exhibition, Frida Kahlo: Art, Garden, Life. Kahlo lived in Casa Azul (The Blue House) her entire life and became a keen gardener, particularly when she became housebound in the 1940s and 50s due to ill health. For the show, the curators recreated the property’s cobalt courtyard walls, a scale replica pyramid used to display her husband Diego Rivera’s collection of pre-Columbian art, and Kahlo’s painting station, which were displayed among ber botanically-inspired artworks. The exhibition, followed NYBG’s 2012 re-imagining of Claude Monet’s flower and water gardens at Giverny.

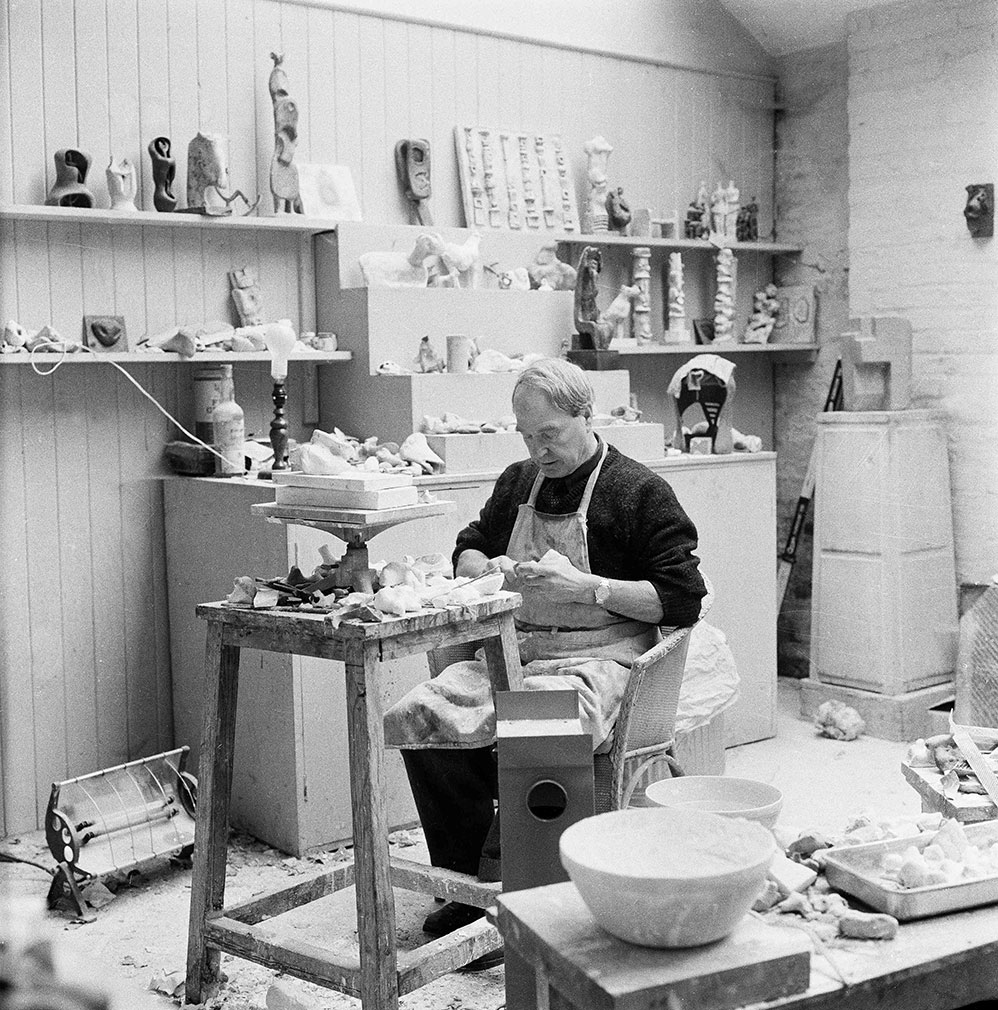

Henry Moore’s studio recreated in London

British sculptor Henry Moore lived in the village of Perry Green, Hertfordshire, from 1941 until his death in 1986. He created maquettes for his most notable works in his studio in the village. The workshop also stashed his sprawling collection of found objects, which included stones, shells, animal skulls and bones. ‘I don’t make my maquettes and models for that purpose of trying to show to somebody else what the big one was going to be like. No, as I make this, the size is any size that I like. I can make it any size in my imagination that I want it to be,’ Moore said of his models. By putting them – and the organic forms that inspired them – side by side, Gagosian’s exhibition showed how these objects, and the sanctuary of Moore’s studio space, helped express his ideas.

Eduardo Paolozzi’s studio recreated in Edinburgh

Italian-Scottish sculptor Eduardo Paolozzi (1924-2005) grew up in Leith, Edinburgh. A recreation of his studio is on permanent display at The Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, alongside artworks he donated. The studio gives a glimpse into one of Britain’s most important post war artists’ methodology, with the room divided into specific areas for reading and working with paper, a central table for modelling and working with plaster-casts. There’s even a bunk for catching a few zzz’s.

Francis Bacon’s studio recreated in Dublin

Moving Francis Bacon’s London studio to the Hugh Lane gallery in Dublin was a painstaking task. Archeologists made a survey and drawing of the Irish-born painter’s tiny studio, mapping the location of objects before they were each tagged and packed – including the dust. Walls, doors, floor and ceiling (which Bacon used as his palette) were also removed and reinstalled over a three year period. ‘It’s much easier for me to paint in a place like this which is a mess,’ Bacon said of the space. The recreated studio – which opened to the public in 2001 – is permanently housed at the Dublin gallery, complete with 7,000 meticulously catalogued items, ranging from empty tins of paint and wine crates.

William Blake’s studio recreated in Oxford

The London house in which artist and poet William Blake produced some of his most famous works was demolished in 1918. Curator and printmaker Michael Phillips chanced upon the floor plans for Lambeth’s 13 Hercules Buildings in the Guildhall library several years ago. Helped by accounts from artists who visited Blake’s studio and home, he was able to recreate the workspace – complete with hefty wooden press – inside Oxford’s Ashmolean gallery. It formed part of a December 2014 show tracing the artist’s life, from apprentice to master.

Piet Mondrian’s Paris studio recreated in Liverpool

To mark the 70th anniversary of Dutch artist Piet Mondrian’s death, Tate Liverpool staged Mondrian and his studios in 2014, exploring the spaces where his ideas were dreamt up. Using a 1926 photograph by Paul Delbo, architect Frans Postma created a replica of Mondrian’s atelier on Paris’ Rue du Départ, where he would host parties for the art world cognoscenti. Writing to his friend Winifred Nicholson in 1936, after he had moved to London, Mondrian exclaimed: ‘the studio is also part of my painting’.

Constantin Brancusi’s studio recreated in Paris

Constantin Brancusi bequeathed his studio and its contents to the French state before his death 1957, on the condition that they would reconstruct it just as it was. The Romanian artist used to arrange his works in ‘mobile groups’, stressing the relationship between the sculptures and the space itself. In the 1920s he used his atelier for exhibitions and, in his final years, stopped creating sculptures altogether, focusing his efforts on their relationship within his studio. The space was partially reconstructed at the Palais de Tokyo before a full replica was produced in 1977 as part of the Centre Pompidou complex. Following a flood in the 1990s, architect Renzo Piano was tasked with creating a new permanent replica. He reproduced the layout, the volume and the light of the original atelier but housed the space inside a larger, square pavilion with a flat roof. Solid walls were replaced with glass to allow visitors to see Brancusi’s works while walking around the outside of the studio.