Photography: Rosella Degori

Photography: Rosella Degori

Photography: Rosella Degori

Photography: Rosella Degori

Photography: Rosella Degori

Photography: Rosella Degori

Photography: Rosella Degori

Photography: Rosella Degori

Tucked behind a red-brick townhouse in London’s Hampstead is a Japanese urban oasis. This peaceful sanctuary – filled with rich foliage, a koi pond and a studio pavilion – is where Greek-born artist Kalliopi Lemos hides herself away to create her work.

Lemos has travelled to Japan many times throughout her life, developing a passion for the country’s distinct design sensibility. ‘Everything is pared down to its essentials,’ she says. ‘I have always loved its simplicity and balance.’

The sculptor and painter tracked down Japanese landscape design specialist Takashi Sawano to create this urban idyll – a labour of love that has evolved over 30 years. In the mid 1990s she tasked designer William Hodgson to create her studio, who coincidentally had a long-held interest in the country’s architecture.

‘He told me he had always wanted to design a Japanese pavilion,’ she says. ‘He was given a maquette by his family as a child that he now keeps in his studio.’

Hodgson built Lemos a light-filled, double-height space beside her home that embraces the garden. From these tranquil surroundings, it is surprising to find such politically charged artworks erupt – installations that tackle human rights issues like forced migration and female repression. But finding a personal equilibrium is a core part of her work, as her new exhibition at Gazelli Art House attests.

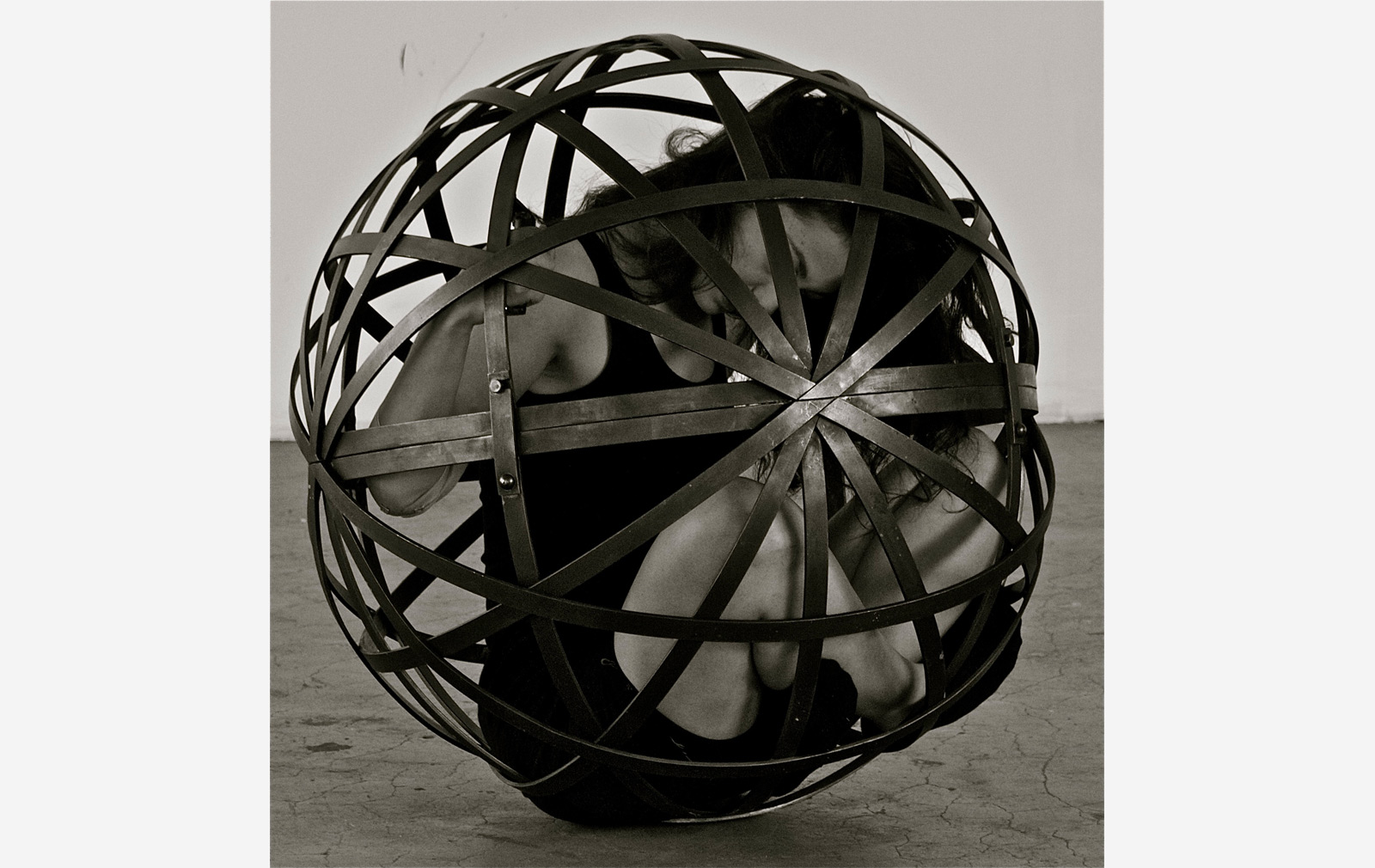

In Balance features are a series of clay figurines wrapped in Japanese paper, whose tormented bodies illustrate a struggle for freedom within society’s constraints. Other works include a video installation (‘At the Centre of the World’) showing a woman struggling to break out of a cage-like iron sphere but finally finding peace within its limited confines.

‘I want to inspire the viewer to question themselves and contemplate life, its dualities and its pressures,’ the artist explains.

Ahead of the show’s opening, we paid a visit to Kalliopi’s Hampstead haven to see where these works were born.

Why a Japanese garden in the midst of Hampstead?

I love the expression of calm that a space like this creates. The garden is beautiful whatever the weather. Japanese gardens have so much richness and variety that you never get tired of them. The greens and textures look different in every type of light.

How does this unusual space impact the work you create?

This studio is my thinking space, where I keep my papers, books and drawings. I do my sketching and maquette-making here. The larger sculptures are made in my studios in Kilburn’s railway arches, because activities like metal cutting need a more industrial space. This pavilion is a meditative environment that helps me go into myself and pull out all the things I want to express.

You studied the Japanese floral art of ikebana for many years. How has that affected your work?

Studying ikebana teaches you to think beyond the arrangement itself and consider the space it occupies. One small object can influence an entire room. In the West, we tend create a volume of flowers or work of art without looking at how it can balance a space. Ikebana has taught me to think about the whole.

The issue of forced migration has long been a theme in your work – one that’s becoming increasingly pertinent today. Was there one incident in particular that triggered this concern?

My Greek paternal grandparents lived in Smyrna [now known as İzmir] within Asia Minor before Greece lost the war with Turkey in 1922, when they were forced to flee. Their sadness when they looked across the water from Greece towards their home has been engraved in my mind ever since. Years later, when I saw the wrecked boats of refugees coming from Turkey to Greece, they immediately resonated with me so I began collecting them in 2003 and making public installations with them. Since that time, the problem has escalated to a terrifying degree.

As human beings, our instinct is to help but when you hear about thousands of people, you feel powerless and inadequate. Through my works, I want to make things feel more human, personal and real so you can imagine other people’s feelings. My pieces talk about a harsh reality but they give these issues dignity and respect.

Tell us about your working process.

It starts as a feeling – a dim light inside me. I also take a lot of inspiration from the materials I use, like reeds, wood and metal. I make a series of drawings and, when that feeling becomes stronger, I start making the first maquette. I’m interested in putting together diverse materials. It’s exciting because every step of the way, there are challenges and choices to be made.

‘Kalliopi Lemos: In Balance’ runs until 24 April at Gazelli Art House, 39 Dover Street, London W1.