There’s an alchemy to designing the perfect concert hall. As well as delivering an unrivalled acoustic experience, they must be beautiful on the eye and serve as a cultural beacon for the city in which they’re ensconced.

No wonder then these delicate buildings often turn into architectural nightmares that run over-budget, over-schedule and under-perform.

But controversy aside, these concert halls hit the high notes.

Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles, USA

The sweeping stainless steel curves of the Frank Gehry-designed Walt Disney Concert Hall have become a landmark of Downtown LA since its opening in 2003. Sixteen years in the making, the concert hall cost twice its initial budget but ranks among the best acoustic designs in the world. In contrast to its contemporary exterior, the main auditorium is made from hardwood for better acoustic performance.

Hungarian State Opera House in Budapest, Hungary

Designed by Miklós Ybl, the Neo-Renaissance Hungarian State Opera House opened in 1884. In addition to the grand marble staircases and horseshoe-shaped auditorium, the venue is filled with paintings and sculptures by the great Hungarian artists of the 19th century.

Harpa Music Centre in Reykjavik, Iceland

Artists, designers and architects from around Scandinavia came together to create this 2011 steel and glass creation by the harbour in Reykjavik, Iceland. Lead architects Henning Larsen worked with local practice Batteríið Architects and Danish-Icelandic artist Olafur Eliasson on the design, including its geometric structure inspired by local basalt formations.

Sydney Opera House in Australia

The great beacon of Sydney Harbour was built in 1973 following designs by Danish architect Jørn Utzon, who worked with engineering legend Ove Arup to make the plan a reality. Utzon famously quit the project during its construction in the 1960s, but its cascading shell-like structure is meant to mimic large white sails of a boat – a reference to the building’s harbour location. Iconic though it is, it looks a lot better than it sounds. Plans are afoot to fix the concert halls’ ‘hideous’ acoustics with a £120m revamp that will take place from August 2019 to January 2021.

National Centre for the Performing Arts in Beijing, China

Nicknamed ‘The Giant Egg’, this titanium and glass dome venue fittingly resembles an egg floating on water. The complex, which includes a concert hall, opera house – which has a reverberation time of around 1.5s – and Chinese theatre was designed by French architect Paul Andreu and inaugurated in 2007.

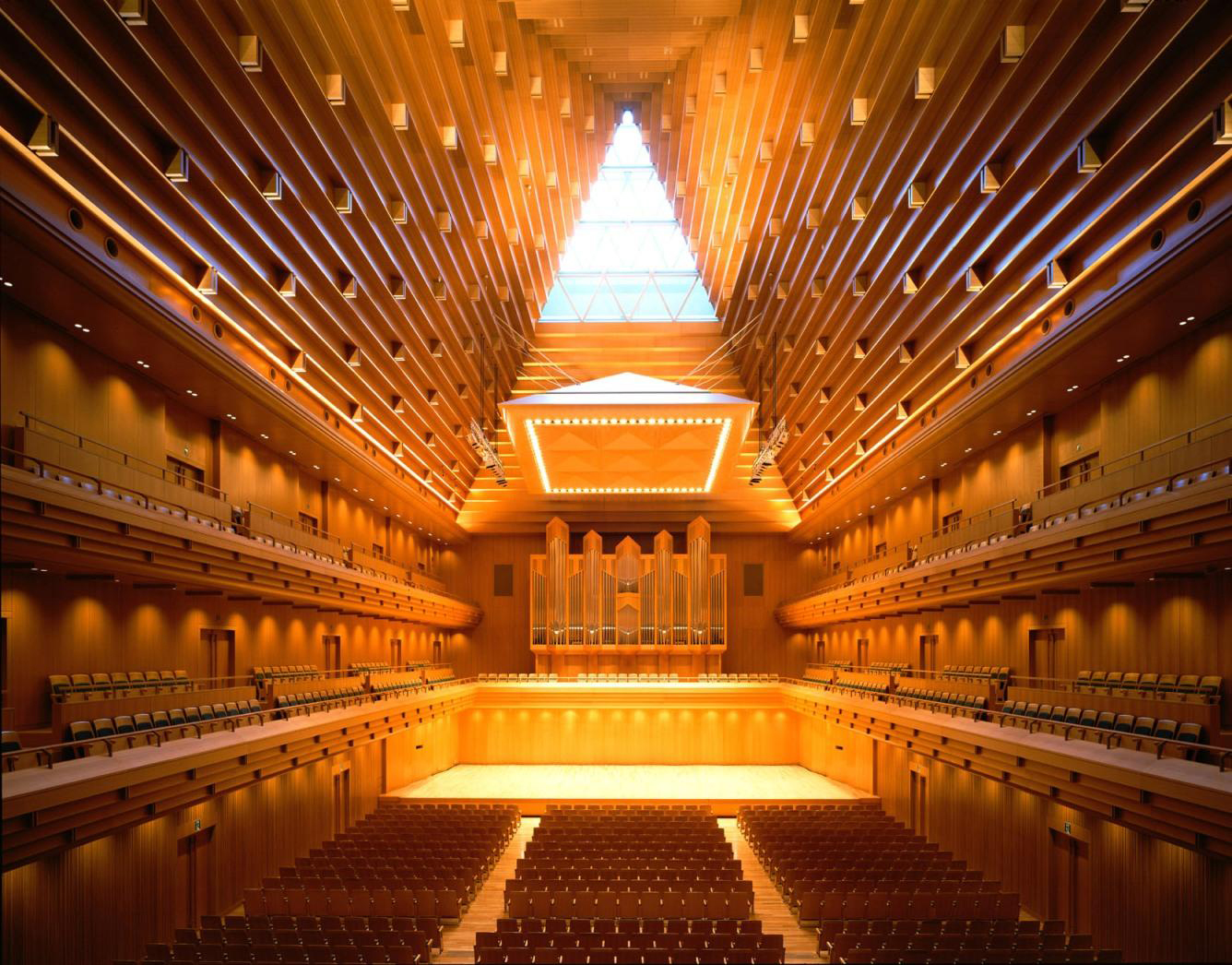

Tokyo Opera City Concert Hall in Japan

This soaring wooden pyramid, which opened in 1997, surprisingly inhabits a glass and metal-clad 54-floor skyscraper in Tokyo. The ridged oak interior is designed for optimum acoustic conditions, and seats 1,632 across its rectangular floor and pair of long balconies. Its unusual vault was designed across the course of five years as a way of distributing sound evenly across all seating areas.

Auditorio de Tenerife in Canary Islands, Spain

The waterside Auditorio de Tenerife takes inspiration from the shape of a crashing wave, but the building’s form looks more like the arch of a scorpion’s tail. Architect Santiago Calatrava designed the white concrete building, which was completed in 2003. In 2011, the concert hall’s name was officially changed to ‘Adán Martín’, after the former president of the Canary Islands, but is still commonly known as the Auditorio de Tenerife.

Guangzhou Opera House in China

Built in 2010, China’s riverside Guangzhou Opera House has the signature touch of the late Zaha Hadid. Its contoured profile was inspired by river valleys and the way they constantly change shape through the process of erosion. Constructed from 12,000 tons of steel, the Opera House includes an 1,800-seat and a 400-seat theatre, each of which are fitted with L-ACOUSTICS sound reinforcement systems, producing an acoustic character its chief sound engineer, Mr Zhou, describes as ‘Not too dry and not too bright’.

Sage Gateshead in Gateshead, UK

Designed by Foster + Partners, the Sage Gateshead contains three freestanding concerts halls. Joining them is a glass and steel shell-like canopy that is said to resemble the shape of a trumpeter’s knuckles. It cost £46m to build and opened in 2004 as part of the Gateshead Quays redevelopment that also saw the arrival of the BALTIC Centre for Contemporary Art and the Gateshead Millennium Bridge. At its peak, the Sage is twice the height of Anthony Gormley’s Angel of the North sculpture. It was also constructed using a special type of concrete that contains extra air bubbles to help control its acoustics and provide sound-proofing.

Carnegie Hall in New York, USA

Famed philanthropist Andrew Carnegie funded the construction of this performance hall in Midtown Manhattan. Built in 1891, the Roman brickwork structure was designed by architect William Tuthill. Carnegie Hall is one of the last remaining places in Manhattan built entirely of masonry and without a steel framework.

Oslo Opera House in Norway

Oslo Opera House is another concert hall to take up a waterside location. Designed by Norwegian architects Snøhetta, the building’s slanting roof acts as an extension of the landscape, while inside a ‘wavy wall’ helps with sound distribution. Oslo Opera House – composed of just stone, wood and metal – opened in 2008.

KKL Luzern (Culture and Convention Centre Lucerne) in Lucerne, Switzerland

Architect Jean Nouvel took full advantage of KKL Luzern’s waterside location in his design for the building. The steel and glass structure – featuring a roof that extends over the lake – frames views of the water while flat aluminium plates on the façade reflect the glistening waves. The building was inaugurated in 2000.

Boston Symphony Hall in USA

McKim, Mead and White – the practice of architect Charles Follen McKim – designed the home of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, completed in 1900. Like Concertgebouw in Amsterdam its design was based on the shoebox-like structure of the second Gewandhaus concert hall, which was destroyed during WWII, in Leipzig.

Wiener Musikverein in Vienna, Austria

Danish architect Theophil Hansen was picked to design the Wiener Musikverein, which would become a cultural landmark for the city of Vienna. He drew inspiration from ancient Greek temples to create the Neoclassical structure, which opened in 1870.

Berlin Philharmonic in Germany

Designed by Hans Scharoun and completed in 1963, the vineyard-style Berlin Philharmonic Hall is known not just for its golden exterior and scalloped roof, but for the way it pioneered a new musical experience. Designed according to the German architect’s observations that people gather in circles when listening to songs, the hall introduced the concept of music in the round. Scharoun developed the building using 1:9 models, to test sound distribution and design its distinctive terraced seating.

Philharmonie de Paris in France

Jean Nouvel’s ‘big metal mountain’ – as The Guardian described it – was completed in 2015 amid a flurry of controversy around its bloated budget and many delays. Its own architect may have refused to turn up to the building’s opening, but it’s undoubtedly one of the most striking structures in Paris. Clad in interlocking aluminium tiles, and often compared to a crashed spaceship, the auditorium sits 2,400 in its curved white interior.

Acoustics were overseen by four groups of engineers, and visitors are seated in stepped levels reminiscent of Hans Scharoun’s Berlin Philharmonic.

Sala São Paulo in Brazil

Inhabiting a converted waiting hall inside São Paulo’s Júlio Prestes railway station, this auditorium counteracts the sounds of passing trains with a vibration-absorbing floating floor. An adjustable ceiling designed by Artec includes fifteen enormous panels that can be individually controlled to adapt the acoustic environment for each performance. Renovated by architect Nelson Dupré, the hall retains the station’s original 1920s features, including stained glass windows and a set of 32 towering columns.

Harbin Opera House, China

Beijing studio MAD designed the Harbin Opera House – the lynchpin of the Harbin Cultural Island arts complex – ‘in response to the force and spirit of the northern city’s untamed wilderness and frigid climate’. Sitting among the wetlands of the Songhua River, the 79,000 sq m building’s form echoes the undulating marshland landscape with a facade of white aluminium panels and glass. Inside, it’s a more natural affair. A concert hall made with Manchurian ash walls ‘emulates a wooden block that has been gently eroded away,’ says MAD.

DR Koncerthuset in Copenhagen, Denmark

‘The first idea for the building was the concept of the blue screen, a kind of lantern magic,’ says French architect Jean Nouvel of his cubic Koncerthuset hall in Copenhagen. Wrapped in a semi-transparent screen that shows projections at night, the building houses a concert hall that seats 1,800, as well as three recording studios. The interior is framed by undulating concrete walls that support terraced wooden balconies, and the acoustics were designed by the same team that worked on Nouvel’s Philharmonie de Paris concert hall. In 2007, it was the most expensive concert hall ever built.

Teatro Regio in Turin, Italy

When the original Teatro Regio burnt down in the 1930s, a competition was launched to design its successor. The onset of WWII derailed plans however, and it wasn’t until 1973 that the new theatre was completed, to a design by architect Carlo Mollino. He connected the theatre’s surviving 1740 wing to his new addition via a pair of symmetrical glazed walkways. Mollino’s auditorium features a field of hanging glass stalactites that light the space and a hall flanked by curvaceous individual boxes. The acoustics were given a spruce in the mid 1990s with the insertion of a picture-frame opening over the oval proscenium arch.

Concertgebouw in Amsterdam, Netherlands

Dutch architect Adolf Leonard van Gendt took cues from Martin Gropius’ Gewandhaus concert hall in Leipzig when designing Amsterdam’s Concertgebouw. Its main concert hall, completed in 1888, is 44-metres long and has a reverberation time of 2.2 seconds with a packed-out audience. This makes it ideal for the late Romantic compositions popular at the time. In the 1960s, rock bands including Led Zeppelin, The Who and Pink Floyd performed there, looking to make the most of its unique acoustic character.

Read next: 10 buildings with extraordinary acoustics