Rome: “The most wonderful movie set in the world”

By: Thomas Lyons

Rome: “The most wonderful movie set in the world”

Inside the Cinecittà film studios and the city’s most cinematic landmarks

Words & photography Thomas Lyons

Rome is the second stop on our slow travel across Southern Italy. Thomas Lyons visits the backlots of Cinecittà and Fellini’s favourite haunts to see whether celluloid fantasy matches up to the real thing.

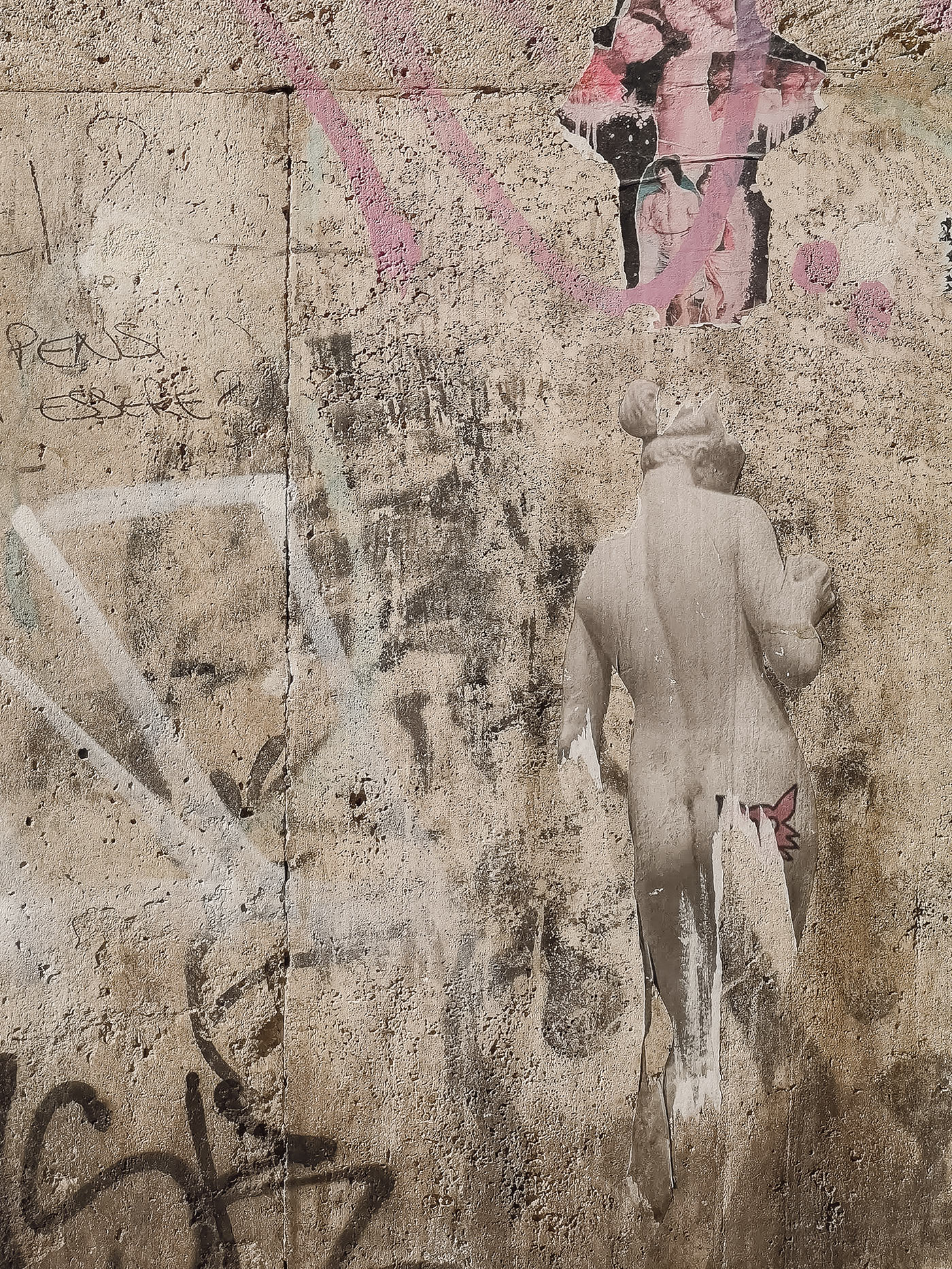

As you walk around Rome, it seems like every street corner, backdropped by ancient ruins, has been immortalised on film. It's arguably the most photogenic city in the world (apart from Paris) and was designated the 'Creative City of Film' by UNESCO in 2015. Every October, it hosts the Rome Film Festival too, and it’s this cinematic version of Rome, captured in Roman Holiday and La Dolce Vita or The Talented Mister Ripley, that compelled us to visit.

Hollywood on the Tiber

The City of Film can trace its roots back to the 1930s and the Cinecittà studios, designed by architect Gino Peressutti. He toured film studios in Berlin, London, and Paris and studied Hollywood before conceiving Rome's studios in the simple, square Rationalist style of the 1930s.

Cinecittà was built outside the city, in the Agro Romano, where flocks of sheep graze amid the ancient aqueducts of the Roman Empire. The timing meant it was an ambitious flagship project for the new fascist regime, and the 'City of Cinema' was to represent the synthesis of classicism and modernity, constructed in just 13 months. 'Cinema is the strongest weapon' was Mussolini's message at its inauguration in 1937, implying that its output would be used only to make impressive nationalistic products.

As it transpired, of the 279 films shot there during World War II, only 17 were propaganda.

The rest were a mixture of comedies, exotic adventures and passionate dramas, elegant musicals, and crime stories – often with a romantic twist. The war barely interrupted the flow of films from the studio: director Alberto Lattuada returned to shoot the last scenes of Giacomo L'idealista in his uniform before heading back to the front again.

Hollywood movies were banned in Italy in 1940, so Cinecittà created its own stars to mimic Errol Flynn and Joan Fontaine. Locals Amedeo Nazzari and Maria Denis emerged as stars, their movies filling cinemas – and their romances, the pages of Italian gossip magazines. Cinecittà offered a utopian fantasy for thousands of restless young Italians during the war.

“In 'Roma,' I wanted to get across the idea that underneath Rome today is ancient Rome. So close. I am always conscious of that, and it thrills me. Imagine being in a traffic jam at the Coliseum! Rome is the most wonderful movie set in the world... As was the case with many of my film ideas, it was inspired by a dream” – Federico Fellini

A new way of seeing

When the Allies reached Rome in 1944, the studios were bombed and collapsed, and the dream shattered.

But out of the city's rubble came an unexpected new style of filmmaking, created in the gloomy bombed-out buildings by war-weary citizen auteurs. They spoke to a different kind of Italy – one with a new future. With film scarcely available, in 1945, Roberto Rossellini shot the first Neo Realistic film, Roma città aperta.

Many others followed, and the new cinema truly brought the promises of Cinecittà to life as ordinary people became stars, such as Lamberto Maggiorani, a factory worker in Rome and the star of Ladri di biciclette. Carlo Battisti was a retired professor and the brilliant Franco Interlenghi, a fifteen-year-old student who would later become one of Fellini's 'Vitelioni'.

With this renewed passion for cinema, Hollywood on the Tiber, as it was known, would also make a return from the ashes with a rebuilt Cinecittà.

Cinecittà 2.0 and the Fellini years

From 1950, the epic Ben Hur - and other less lavish sword and sandal films such as Quo Vadis – would be shot at the new studios, including William Wyler’s iconic 1953 movie Roman Holiday, starring Audrey Hepburn in her Oscar-winning breakout role beside Gregory Peck. Movie plots were devoted to Greek mythology, Roman emperors and events inside the blood-thirsty Colosseum. Today, huge sets of Roman architecture still litter the backlots.

This Roman epic trend lasted until 1964, when public interest began to fade, only for the 'Spaghetti Western' to pick up: Italy served back this American diet to an eager public.

Perhaps the most famous resident of Cinecittà was director Federico Fellini. He adored 'Teatro 5 Stage' and shot his most famous films there, including La Dolce Vita, his first homage to the city. (He moved to Rome in 1939, becoming a writer at Cinecittà the following year.)

What to do:

DRINK: Harry's Bar The legendary haunt was a favourite with Marcello Mastroianni, Anouk Aimée, Truman Capote, Jean-Paul Belmondo, and the paparazzo. Via Vittorio Veneto, 150, 00187 Roma RM, Italy

EAT: Latteria Trastevere has great inventive food and a very extensive wine list, including natural choices. Vicolo della Scala, 1, 00153 Roma RM, Italy

STAY: Hotel De'Ricci, in the heart of Rione Regola, is one of the most authentic neighbourhoods in Rome. Via della Barchetta, 14, 00186 Roma RM, Italy

SEE: Cinecittà Shows Off at Cinecittà Studios, Via Tuscolana 1055 – 00173 Rome Visit in October for the Rome Film Festival

In 2020, his great friend (and the architect of his visions) Dante Ferretti created Ferretti dreams Fellini at Cinecittà – a permanent museum dedicated to the director. Its central room hosts a Fiat 125, the symbol of the director and production designer's ritual journey to Cinecittà each morning, and the same model that Fellini loved driving through Rome at night, carting his friends around and discovering strangers to who'd become his new stars.

'We'd go to Cinecittà early in the morning together: Dantino, what did you dream about last night? Nothing, I don't remember. After about a week, I'd start inventing dreams… He knew full well that I was making it all up.'

Fellini always borrowed heavily from his surroundings. When the Turkish dancer Haish Nana improvised a striptease at a Rome nightclub, Fellini used it as the finale for his script-in-progress, Moraldo in the city (later to become La Dolce Vita), with an all-night 'orgy' at a seaside villa. Anita Ekberg's famous scene in the Trevi Fountain was inspired by Pierluigi Praturlon's photos of her wading in it on a previous occasion. The statue of Christ being flown by helicopter to St Peter's Square in the city was borrowed from a real-life media event in 1956, which Fellini had witnessed.

Paul Newman was almost cast as the lead, but it would be difficult to imagine it now without Mastroianni, then still relatively unknown, in the role.

The producers needn't have worried, as the film broke all box office records on its release. Crowds queued in line for hours, and scalpers sold tickets at 1000 lire to see the 'immoral movie'. Attacked by parliament conservatives and the Vatican, it proved that all press is good press, as it went on to win the Palme d'Or that year.

Fellini's films would develop far beyond Neo-Realism. His experiments with Jung, LSD and the I Ching meant he began to interpret his dreams as psychic manifestations of unconsciousness, directly influencing his mature films like 8 1/2 and Satyricon.

Satyricon was loosely based on Petronius's work, written during the reign of Emperor Nero and set in Imperial Rome. The original text survives only in parts, and Fellini was fascinated by the text's fragmentary nature. It encouraged him to 'eliminate the borderline between dream and imagination: to invent everything and then to objectify the fantasy.'

Many scenes were shot below the Colosseum and at the backlot of Cinecittà, itself built on the site of ancient ruins. It is hard to say which is the bigger fantasy.